Florence Gelo

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States

On Thanksgiving Day, I watch my niece Jenn with her seven-month-old daughter Laila playing on the living room floor. Jenn’s gaze has never left Laila despite the commotion nearby made by family who are setting the table for dinner, moving furniture to add additional chairs. The kitchen is lively. Utensils removed from the cupboard bang against dishes, voices comment on the cranberry sauce and mashed potatoes, and another exclaims, “These pies look glorious!” There are shouts of delight when someone hollers, “Hooray, the turkey is done!”

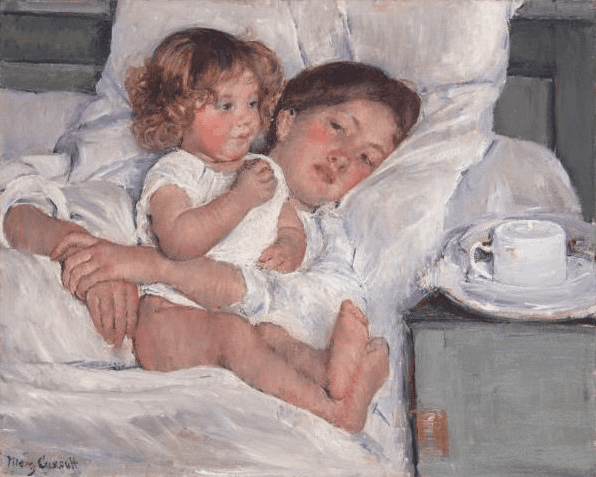

Jenn’s intimate and watchful look reminds me of the painting Breakfast in Bed by Mary Cassatt where a young mother lovingly gazes upon her fair-haired child. No matter that Laila has dark curly hair and chocolate brown eyes.

Mary Cassatt, an American painter living in Paris, was known for her portrayals of the social and domestic life of affluent women in the late nineteenth century. She is particularly known for portrayals of the intimate bonds between mother and child in the everyday spaces of the home. Breakfast in Bed, housed at the Huntington Library and Art Collection in San Marino, California, is one such portrayal.

The mother, lying in bed, head on a voluminous pillow, gently wraps her arms around her young child. Mother and child seem cozy, physically together in a casual moment of closeness, while both are absorbed in separate musings. The mother’s expressive gaze is not grasping. Her tranquil eyes look tenderly at her child and beyond. She appears contemplative. The child, on the other hand, is looking at the cup on the side table.

What I wonder about is the look on the mother’s face—looking out and looking beyond. Knowing that as a child Cassatt had experienced the death of several siblings, I wonder if she painted the mother’s gaze as if the mother knows, or at least surmises, that life will ultimately be crossed by shadow.

That speculation makes me think about my niece, looking at her little baby.

Propped up on one elbow, her cheek resting in her palm, she stretches out on the carpeted floor beside Laila. She gazes at her daughter, with that same non-grasping and attentive gaze of the mother in Breakfast in Bed. I see that Jenn is looking at her child, this little being she has fallen in love with and yearns to keep safe and well.

Jenn’s posture becomes a visual metaphor. It communicates a message to Laila: When you push yourself up, tip sideways on your shoulder, or tumble forward, slump, or fall, I, your mother, now and forever, will be here for you. During periods of rest, I will rest with you.

When I look at Breakfast in Bed, I see an image imbued with the nuances of an all-embracing love and fervent devotion. The mother is glancing at her child and the child glances away. The mother’s gaze is a looking at her child and looking beyond to an unknown life yet to be lived, while also looking in—eyes soft, still, and reflective of what only the tender heart can conceive. The glance betrays a knowing that she will not take every step with her daughter. I wonder if she already knows that this so-loved bundle will one day face the world as it is, and often alone?

I suppose one could say that Cassatt dared to tell a truth as she painted the life of a mother and child, both absorbed in the shared and solitary everyday world. As peaceful and content as mother and child appear in Breakfast in Bed, Cassatt embeds, in an exquisite expression on the mother’s face, her internal wisdom about the fullness of love, its fragility and vulnerability. The evidence of this knowing is embodied in Cassatt’s painting of a powerful gaze.

Cassatt was present when her mother and father experienced the torments of loss. Two of Cassatt’s siblings died in infancy when Cassatt was a child. Though too young to understand the permanence of death and its impact on loved ones, Cassatt would have absorbed the grief that saturated the air in every room and shaped life within and around her mother, who suffered multiple losses—even one of which would have challenged a mother’s ability to endure.

Zerbe,1 in a biographical portrait of Mary Cassatt, theorized from a psychoanalytic perspective that the “eventual choice of artistic subject, robust and healthy children,” results in part from a wish to “bring her lost siblings back to life to have them live eternally on canvas.”

Dr. Zerbe offers a compelling interpretation. To enable a loved one to live forever can ease the anguish. I interpreted the painting differently, not as “bringing back to life,” but as hope to move forward into an unknown future. Love will demand a full embrace and a full recognition and acceptance of the inevitability of letting go.

In the ways that paint allows bodies to touch and embrace, gestures to communicate, and eyes to look upon and beyond, Cassatt succeeds in giving viewers a glimpse of that which transforms vulnerability into enduring hope. The image propels me forward to witness how we love so fiercely.

That Thanksgiving, I witnessed the intimacies of love present in a family moment. Whether in a living room watching my niece and grandniece, or at the museum looking at a painting, I am moved by the courage to yield to love.

End note

- Zerbe KJ. Mother and child. A psychobiographical portrait of Mary Cassatt. Psychoanal Rev. 1987 Spring;74(1):45-61.

FLORENCE GELO is a medical humanities and behavioral science educator. She directed and produced “The HeART of Empathy: Using the Visual Arts in Medical Education,” and uses the visual arts as a teaching tool to enhance clinical skills. She has published numerous articles in professional journals about illness, death and dying. Her most recent project used images of narrative paintings to assist hospice patients to speak about the day-to-day realities of living while dying.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 14, Issue 3 – Summer 2022