Howard Fischer

Uppsala, Sweden

|

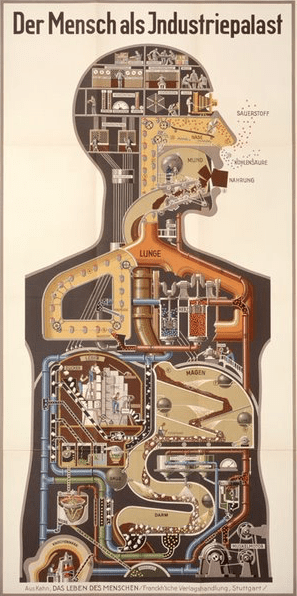

| Der Mensch als Industriepalast (Man as Industrial Palace). A human head in profile divided into offices, staffed by little men, and areas of industrial production. Artwork by Fritz Kahn in Das Leben des Menschen; eine volkstümliche Anatomie, Biologie, Physiologie und Entwick-lungs-geschichte des Menschen (Kosmus publishers, Stuttgart, 1926). Chromolithograph. Via the US National Library of Medicine. |

“If I were…an intern just getting ready to begin, I would be apprehensive that my real job, caring for sick people, might soon be taken away, leaving me with the quite different occupation of looking after machines.”

— Lewis Thomas, MD, 1983

Dr. Fritz Kahn (1888–1968), a Berlin gynecologist, realized that society’s fascination with the twentieth century’s new technologies could be used to teach people about the functioning of the human body. These technologies included the telephone, x-rays, anesthesia, the electric light, the typewriter, film, elevators, the internal combustion engine, and the automobiles and airplanes that they moved.1

His method of informing the public has become known as “infographics,” a term derived from “information” and “graphics.” Infographics are “graphic visual representations of information, data, or knowledge intended to present information quickly and clearly.”2 Kahn sought to “remove the mystery from biology and pathology by presenting it through words and pictures that most people could comprehend – and even enjoy.”3 For example, he used drawings to compare the eye to a camera, enzymes to tiny workers breaking down complex packages, and the brain to a group of homunculi reading, discussing, and planning. The illustrations he used in his publications were clear, interesting, understandable, and sometimes whimsical. Like Vesalius, he did not make the drawings himself, but had a team of artists, designers, and architects who created the images according to his directions. Unlike the work of the American surgeon-artist Frank Netter, these illustrations did not depict anatomy in a lifelike, realistic way. Some of Kahn’s illustrations received “contempt from academically-trained readers.”4

We are, in fact, surrounded by infographics. The maps of transit systems, which integrate the layout of the network and the transfer points, are infographics and so are bar graphs and pie charts. The plaques sent into space on the Pioneer 10 and Pioneer 11 spacecrafts were NASA-created infographics showing what human male and female bodies look like, as well as indicating the terrestrial origin of the spacecraft.5

During his career, Kahn wrote twenty books. He started writing his five-volume bestseller The Life of Man (Das Leben des Menschen), which sold 70,000 copies and contained more than 1500 images, while he was a combat surgeon in France during the Great War. This masterwork shows the structure and function of every body system, as well as much biochemistry and physiology. When he describes the skeletal system, the bones are visually compared to structures used in engineering support. We also learn that “the 22 trillion blood cells in a man’s body would, if laid in a line touching each other, go more than three times around the equator.”6 Other topics in this series include nutrition, temperature regulation, and sexuality. Kahn’s other books describe comparative anatomy, evolution, continental drift, and chemistry and isotopes.

A most important Kahnian educational concept was the image of “Man as Industrial Palace” (“Der Mensch als Industriepalast”), which “tries to show the most important processes of life, which can’t be observed directly, in the form of technical processes so as to provide an overall picture of the human body’s inner life.”7

Another interesting and rather prophetic idea Kahn had was “The Doctor of the Future” (“Der Artz der Zukunft”). The doctor is seated at a desk (cigarette in his mouth), and the names of his patients are before him, a button next to each name. He faces a large screen on which there are the patient’s electrocardiogram, respiratory rate, and a graphic representation of the depth of respiration, blood pressure, temperature, and heart rate. A speaker plays the patient’s heart sounds, and the doctor can call up x-ray films to examine. This is a reason Kahn has been called “a visionary of modern telemedicine.”8

Many of his illustrations were used (usually without acknowledgement) by public health agencies, magazine illustrators, and poster artists in several countries, including the USSR.9

Kahn was a Jew and a pacifist. In 1933 he was expelled from Germany. He arrived in neutral Portugal by a circuitous route and was granted a visa to come to the US in 1941, partly through the efforts of Albert Einstein. The New York World’s Fair of 1939 had a display based on his “Where the brain’s most important functions take place.” In 1943 Life magazine ran a seven-page article on Kahn and his work.10

The Life of Man was well-received on both sides of the Atlantic. Dr. Wilhelm von Gozenbach, professor and head of the Institute for Hygiene in Zürich, Switzerland, suggested that medical students read Kahn.11 Logan Clendening, MD, wrote in the New York Times in 1943, “I wish this book were used…in all of our high schools.”

Indeed, for freshmen in medical schools it would be no bad discipline.”12 Cornelius Borck, historian of medicine and science, calls Fritz Kahn “one of the most successful popular science writers internationally between 1920–1960.” He also notes that Kahn’s work has been translated into nine languages, including Chinese and bahasa Indonesia.13 Anthropologist Earnest Hooten in 1943 thought that Kahn’s Das Leben des Menschen–sold in the US as Man in Structure and Function–”deserves a place in the library of every family.”14

Despite the popularizing and the technological and mechanical analogies, Kahn always considered “the wonders of nature to be far superior to the wonders of technology.”15

References

- NA. “Technoscientific bodies, “Issues in Science and Technology, ND. issues.org

- Infographic-Wikipedia.

- Uta von Debschitz and Thilo von Debschitz. Fritz Kahn, Köln: Taschen, 2013.[Author’s note: This is a nearly 400-page book with 350 illustrations. It weighs six pounds and is beautiful and fascinating to read.]

- von Debschitz.”Fritz Kahn.”

- Infographic-Wikipedia.

- von Debschitz. “Fritz Kahn.”

- von Debschitz. “Fritz Kahn.”

- von Debschitz. “Fritz Kahn.”

- Elma Brauer. Social History of Medicine, 30 (2), 2017.

- Brauer. “Social.”

- Annie Minoff. “Fritz Kahn’s fantastical journey through the body,” 2013. sciencefriday.com

- Logan Clendening. “Guide and chart for the human interior. Book review of ‘Man in Structure and Function,’” New York Times, 4 April 1943.

- Cornelius Borck. “Communicating the modern body: Fritz Kahn’s popular image of human physiology as an industrialized world,” Can J Communic, 32, 2007.

- von Debschitz. “Fritz Kahn.”

- von Debschitz. “Fritz Kahn.”

HOWARD FISCHER, M.D., was a professor of pediatrics at Wayne State University School of Medicine, Detroit, Michigan.

Leave a Reply