Howard Fischer

Uppsala, Sweden

Primum non nocere. (First, do no harm.)

— Hippocrates

Robert Koch, M.D., (1843–1910) started his career as a country doctor and discovered the causes of tuberculosis, anthrax, and cholera. He is considered to be, along with Louis Pasteur, the founder of the field of bacteriology. Awarded the Nobel Prize for Medicine and Physiology in 1905, he spent the last few years of his life trying to find a cure for African sleeping sickness. His research in Africa, however, was tainted by a breach in medical ethics.

By the age of thirty-three, he had studied the life cycle and infectivity of Bacillus anthracis, the bacterium that causes anthrax. He practiced in a wool-producing district and had many opportunities to see patients with anthrax.1 The organism is often transferred to humans from animal hides, hair, and wool. His discovery, made in his makeshift laboratory, led to his later appointment to the Imperial Health Department, where he had a modern, well-funded laboratory for his research. In 1882 he discovered and described Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the causative organism of human tuberculosis. The following year he discovered Vibrio cholerae, the cause of cholera. These discoveries led to his receiving the Nobel Prize in 1905.2

The way to implicate an organism as the cause of an infectious disease has been elucidated in what we now call “Koch’s Postulates.” The three original postulates are:

- The organism is found in every case of the disease in question.

- It occurs in no other disease.

- After being isolated and grown in pure culture, it can induce the disease.3

Human African trypanosomiasis (“sleeping sickness”) is a disease caused by trypanosomes, which are long, motile protozoa. Livestock may also become infected.4

Early in the course of sleeping sickness, the patient may have joint pains, headache, fever, and swollen lymph nodes in the neck in West African trypanosomiasis. The episodes of fever may mistakenly be thought to be malaria.5,6

East African trypanosomiasis is caused by Trypanosoma rhodesiensis. This is the more acute disease, with malaise, fever, and death occurring three to twelve months later from myocarditis and anemia. The patient dies before encephalopathy begins.

West African trypanosomiasis, caused by T. gambiense, is a more chronic disease, and months or years may pass before the organisms enter the central nervous system. Once the organism crosses the blood-brain barrier (a selective semi-permeable membrane that keeps certain solutes and other substances from entering the cerebrospinal fluid) and enters the central nervous system, lethargy or insanity appears, followed by coma and then death.7

Outbreaks of sleeping sickness started to occur in Africa at the turn of the century. An outbreak from 1896–1906 in Uganda and the Congo killed 800,000 people.8 This alarmed the European colonial powers. With a diminished workforce, profits fall. Loss of livestock hindered transportation and communication.

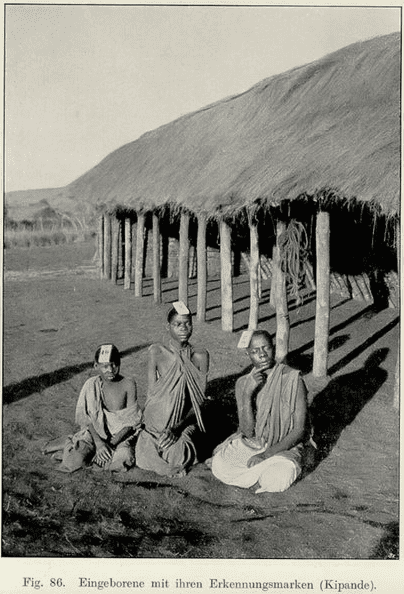

Dr. Koch was sent to Africa to find a cure for sleeping sickness in 1906. Because it was “not desirable to test new medications on Europeans,” Africans became test subjects. “Research camps,” also referred to as “concentration camps,” were set up to treat Africans infected with sleeping sickness – whether they were willing or not – and to keep them isolated from the general population. They were made to wear wooden identification tags around their neck. Up to 1000 people per day were treated in the three concentration camps in German East Africa9 (today’s Rwanda, Burundi, and Tanzania).

“European humanitarianism consisted of a mixture of benevolent condescension and outright racism.”10 This was clearly expressed in the phrase koloniale Menschenökonomie11 (colonial human economy), behind which was the idea that indigenous people are like commodities or livestock.

Besides imprisoning his patients, Koch was testing “atoxyl,” an organic arsenical compound. Arsenic had long been used in human medicine, sometimes with beneficial results. Atoxyl injections did clear the bloodstream of trypanosomes, but they reappeared, even as treatment continued. These injections were painful, and the drug produced dizziness, vomiting, diarrhea, jaundice, and nephritis.12 Patients sometimes developed symptoms of arsenic poisoning.13 Of the 1600 people treated, there were twenty-two who became blind from optic nerve atrophy. Atoxyl does not cross the blood-brain barrier, so it could not affect any organisms already in the central nervous system.14 Thus, the “therapeutic value of atoxyl was limited,” and its “curative value was dubious.”15

Because the drug produced only short-term clearing of the parasites from the blood, and did not produce any real benefit to the patients, a question arises: What was the point of treatment? One possibility is that with patients isolated in camps and temporarily free of parasites, there would be less spread to the general population. We cannot know if this was a sort of “public health measure,” albeit against the patients’ will, or an attempt to preserve the colonial economy by limiting the transmission of the disease.16

Ananthavinayagan17 quotes the psychiatrist-turned-revolutionary Frantz Fanon: “With medicine we come to one of the most tragic features of the colonial situation… for the colonized interprets the medical injunction as a new form of torture, of famine, a new manifestation of the occupant’s inhuman methods.” The premier infectious disease research facility in Germany is named for Robert Koch. There is presently a movement to remove his name from the institute.18

References

- Howard Markel. When Germs Travel, New York: Pantheon Books, 2004.

- Fielding Garrison. An Introduction to the History of Medicine, Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Company, 1966.

- Thomas Rivers. “Viruses and Koch’s postulates,” J Bacteriol, 33(1), 1937.

- Daniel Headrick. “Sleeping sickness epidemics and colonial responses in east and central Africa, 1900-1940,” PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 2014.

- Mike Seear. “Trypanosomiasis,” In Manual of Tropical Pediatrics, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

- Headrick. “Epidemics.”

- Seear. “Trypanosomiasis.”

- Dietmar Severding. “The history of African trypanosomiasis,” Parasites and Vectors, 1, 2008.

- Edna Bonhomme. “When Africa was a German lab”|Health|Al Jazeera, 2020.aljazeera.com

- Headrick. “Epidemics.”

- Steverding. “History.”

- NA. “A fatal case of poisoning by atoxyl,” Lancet, 19 June 1909.

- Matthew Jackson. “Studies in trypanosomiasis, with special reference to the adhesion test,” University of Glasgow, ProQuant Dissertation Publishing, 1936.

- Bernard Bouteille and Marc Dumas. “La maladie de sommeil de Janot à nos jours ou l’histoire de la lutte contre ce fleau,” Revista di Parassitologia, XXII, (1), 2005.

- Steverding. “History.”

- Steverding. “History.”

- Thami Ananthavinayagan. “Robert Koch, research and experiments in the colonial space, or: Subjugating the non-European under the old international law,” Völkerrechtblog, 10 June 2020.

- Anders Jeppson. “Robert Koch, arseniken, och koncentrationslägern,” Läkertidningen, 119, 2 Feb 2022.

HOWARD FISCHER, M.D., was a professor of pediatrics at Wayne State University School of Medicine, Detroit, Michigan.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 14, Issue 3 – Summer 2022

Leave a Reply