JMS Pearce

Hull, England, United Kingdom

|

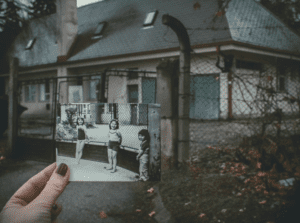

| Photo by Anita Jankovic on Unsplash |

In these troubled times imposed by Covid-19, much attention has been paid to depression, stress, and complaints of enforced isolation and of longing for the old days—the “normal times.” In this and in other contexts, nostalgia is regarded as a normal sentiment with no implication of disease or illness. But this was not always so. Nostalgia, in modern language, implies a yearning for home or past memories and experiences, usually of a pleasant nature, yet tinged with sadness at their passing.1

Scholars of linguistics recognize how commonly words change their meaning and context. Nostalgia is a case in point. The word stems from the ancient Greek νόστος “return home” and αλγία “pain.” For many years it was far more than a wistful memory of people or past happenings. It was a medical illness. The Swiss medical student Johannes Hofer (1669-1752) of Mühlhausen in Alsace minted the word in his dissertation in 1688.2 He recorded an existing term das Heimweh—used by Helvetians for the grief after leaving their native land. He believed it was caused by:

the quite continuous vibration of animal spirits through those fibers of the middle brain in which impressed traces of ideas of the Fatherland still cling.

Hofer described two patients. One, a student from Bern, lonely and sick while studying and living in Basel, was beset by severe and increasing anxiety, fatigue, palpitations, and a fever. Only when sent home to die did he amazingly recover. The second was a servant girl who had an accident forcing a stay in hospital far from home. She too developed a grave emotional illness from which she recovered only when her parents took her home. Hofer believed that nostalgic memories deprived the brain of essential vital spirits and ultimately caused a pathological illness, Pothopatridalgia vom Heimwehe.

Psychologists often regard nostalgia as an adaptive defense mechanism, but this fails to explain the common refusal of World War soldiers and Auschwitz survivors to talk of their horrific experiences, even to their close relatives.

Of course, the symptoms had already been recounted,3 notably in Shakespeare’s Sonnet 30:

When to the sessions of sweet silent thought

I summon up remembrance of things past,

I sigh the lack of many a thing I sought,

And with old woes new wail my dear time’s waste:

Then can I drown an eye, unus’d to flow,

For precious friends hid in death’s dateless night,

And weep afresh love’s long since cancell’d woe,

And moan th’ expense of many a vanish’d sight . . .

And it appears in Edmund Spenser’s 1595 poem “Colin Clouts Come home againe.” And William Cowper’s “The Task” (1785) relates a sailor’s dreams of home:

Upon the ship’s tall side he stands, possess’d

With visions prompted by intense desire;

Fair fields appear below, such as he left

Far distant, such as he would die to find—

Initially, nostalgia was thought to be confined to Swiss soldiers distanced from home, who, hearing a familiar milking song would be saddened by thoughts of home. Nostalgia was soon accepted as a disease in Europe and America. During James Cook’s voyage (1768-71) in HMS Endeavour, Sir Joseph Banks observed in scorbutic sailors:

The greatest part of them [sc. the ship’s company] were now pretty far gone with the longing for home which the Physicians have gone so far as to esteem a disease under the name of Nostalgia.

In 1782 Thomas Arnold MD (1742–1816) included nostalgia in his Observations of the nature of Insanity:

A variety of, pathetic insanity, to which, from nostalgia its most usual appellation, I have given the epithet nostalgic.

Faking nostalgic illness to secure military discharge was also common. However, treatment of afflicted victims could be harsh, frightening, and bullying. Nostalgia was prevalent during the Thirty Years War (1618 and 1648), and the Napoleonic and other wars in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. But a hundred years later, romanticized by Byron, Wordsworth, Burns, and Rousseau among others, it was often regarded as a type of melancholia.

Marcel Proust’s major seven volume novel À la recherche du temps perdu [Remembrance of Things Past] published in 1913 borrowed its title from Shakespeare’s sonnet and is filled with memories of childhood and youth.

By contrast, the complex ruminations of Oscar Wilde in his The Picture of Dorian Gray seek escape from nostalgic sentiments:

. . . a world in which the past would have little or no place, or survive, at any rate, in no conscious form of obligation or regret, the remembrance even of joy having its bitterness and the memories of pleasure their pain.

Nostalgia was eventually discharged from the dungeons of medicalized illness when its meaning slowly changed4 to an essentially harmless and often wistfully pleasurable experience.

References

- Kevis Goodman “Uncertain disease”: the science of nostalgia. Hektoen International. Fall 2013.

- Anspach CK. Medical dissertation on nostalgia (Dissertatio Medica de Nostalgia, oder Heimwehe). By Johannes Hofer, 1688.). Translated: Carolyn Kiser Anspach. Bulletin of the Institute of the History of Medicine 1934; 2 (6): 376-391.

- Roth MS. Dying of the Past: Medical Studies of Nostalgia in Nineteenth-Century France. History and Memory 1991;3(1):5-29. Indiana University Press.

- Starobinski J. Le concept de nostalgie. Diogène 1966;54: 92–115.

JMS PEARCE is a retired neurologist and author with a particular interest in the history of science and medicine.

Fall 2021 | Sections | Psychiatry & Psychology

Leave a Reply