Charles-Henri Valentin Morhange was a precocious child who played the piano at the age of five and gave his first public performance at seven. He was the second of six children of an old Ashkenazi family that for centuries had lived near the town of Metz in Alsace. Born in Paris in 1813, he later changed his family name to Alkan, his father’s given name. Already as a teenager he was composing original music for piano and organ, and by the 1830s he had become one of the foremost virtuoso pianists in Paris—then the center of culture of Europe, the “city of light.”

It was said that he played the piano faster than Franz Liszt and louder than Frédéric Chopin. He was friends with both, outliving Liszt by over forty years, and was much aggrieved by the early death of Chopin, whom he worshipped. He earned numerous awards for his work, wrote symphonies and concertos, and gave popular music recitals. But after 1840 his career grew to a halt and he withdrew from public life for about six years. When he re-emerged from retirement he again became fashionable. He was, however, repeatedly passed over when applying for professorial teaching positions, especially in 1848 when one of his mediocre students was appointed to the professorial position he aspired to.

At age forty, in 1853 Alkan again became a recluse. In a letter written in 1861 he wrote that every day he was becoming more misanthropic and misogynous. Not until 1873 did he return to public life, and again he delighted audiences with his exquisite piano playing. Eventually, however, his compositions were largely forgotten and were not rediscovered until the 1960s when a long-playing recording of his work was issued.

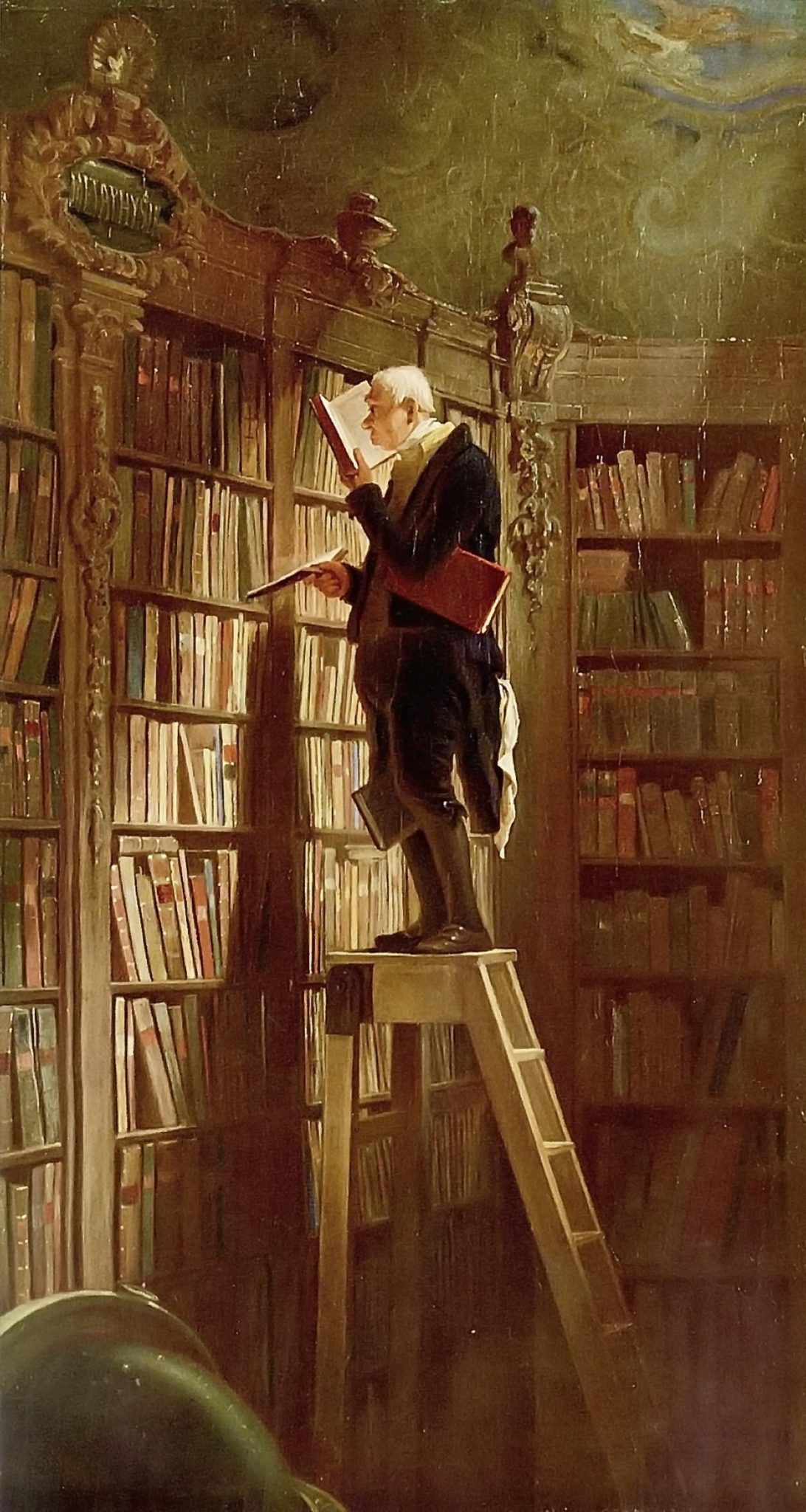

Alkan was subject of many legends and untruths that were spun about him.1 He supposedly wrote music that could only be played by pianists with very big hands. It was claimed that he wrote a funeral march for a dead parrot, and that his natural son kept a menagerie of two apes and a hundred cockatoos in his Paris apartment. The story was also spread that he died by falling from a bookcase while reaching for a copy of the Talmud from the top shelf, a rumor perhaps originating from the virulent anti-Semitism prevalent in France at the time, well described by Marcel Proust, illustrated by the Dreyfus affair, and probably the reason why, despite his early successes, his career did not flourish.

Though described as a warm and humorous person, Alkan was shy and awkward in society. As a young piano teacher he had fathered a child with one of his married students but never married himself. In the face of repeated disappointments, he became reclusive and lonely, depressed, and isolated. He was a cultured man, proficient in Greek and Hebrew, and in his retirement he completed a translation of the Bible into French; at one time he had considered setting the entire Bible to music. He died in 1888 at age seventy-four. It appears that, living alone, he was trapped by a piece of falling furniture for more than twenty-four before being discovered by callers who dragged him free, but he died several hours later.

His music, after being forgotten for so many years, is now widely available, societies commemorating his work have sprung up in England and France, and in 2002 Jack Gibbons gave an excellent précis of his life on the BBC.1

|

|

|

| Charles-Valentin Alkan, standing. Unknown date (believed to be taken c. 1850). Via Wikimedia. | Pastel portrait of Charles Valentin Alkan by Edouard Dubufe. circa 1835. Via Wikimedia. | The Bookworm, by Carl Spitzweg. circa 1850, Museum Georg Schäfer (Schweinfurt, Germany). Via Wikimedia. |

References

- Gibbons J: The Myths of Alkan. Transcript of talk for BBC Radio, 2002.

- Eddie, W. A. Charles Valentin Alkan: His Life and His Music. Ashgate Publishing. 2007.

GEORGE DUNEA, MD, Editor-in-Chief

Leave a Reply