David Blitzer

New York, New York, United States

Alvise Guariento

Toronto, Ontario, Canada

Robert M. Sade

Charleston, South Carolina, United States

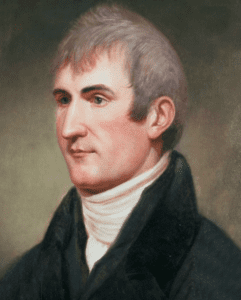

In 1803, Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, with the backing of President Jefferson and the federal government of the newly created United States, set out to find the coveted Northwest Passage, an all-water route through North America. The primary goals of the expedition were geared towards economic and defensive strategy, with the intent of securing trade with the Native Americans inhabiting the lands in the recently completed Louisiana Purchase. Jefferson also saw the potential for scientific advances and charged Lewis with carrying out that portion of the mission. With that in mind, Lewis first went to Philadelphia to study with some of the nation’s leading scientists. One of his teachers was Benjamin Rush, who trained Lewis in the treatment of ailments he was likely to encounter during the expedition. Rush also gave Lewis some related tasks, namely to learn what he could from Native Americans. He asked Lewis to investigate many aspects of medicine, including certain “Moral” questions about Native American customs, such as what were their vices, was suicide common among them, did they use ardent spirits to promote intoxication, was murder common among them, and did they punish it with death?1

By May 1806 the expedition had reached the Pacific Coast and was moving back to the East through the territory of the Nez Perce tribe. The company was now in an impoverished state, with limited food supplies and depleted stores with which to trade; however, they had Clark’s reputation as an excellent physician, which he had established with the tribe when the expedition had passed through its territory on its westward course. In his journal entry on May 5, 1806, Lewis wrote:

. . . while we were encamped last fall . . . Capt. C . . . gave an indian man some volitile linniment to rub his kee and thye for a pain of which he complained . . . the fellow soon after recovered and has never ceased to exol the virtues of our medecines and the skill of my friend Capt C. as a phisician. this occurrence added to the benefit which many of them experienced from the eyewater we gave them about the same time has given them an exalted opinion of our medicine. my friend Capt. C. is their favorite phisician and has already received many applications [for treatment]. in our present situation I think it pardonable to continue this deseption for they will not give us any provision without compensation in merchandize and our stock is now reduced to a mere handfull. we take care to give them no article which can possibly oinjure them.2

In his journal entry from the same date, Clark echoed Lewis’ journal entry:

While we were encamped last fall . . . I gave an Indian man some volitile leniment to rub his knee and thye for a pain of which he Complained. the fellow Soon after recovered and have never Seased to extol the virtue of our medicines. near the enterance of the Kooskooske, as we decended last fall I met with a man, who Could not walk with a tumure on his thye. this had been very bad and recovering fast. I gave this man a jentle pirge cleaned & dressed his Sore and left him Some Casteel Soap to wash the Sore which Soon got well. this man also assigned the restoration of his leg to me. those two cures has raised my reputation and given those nativs an exolted oppinion of my Skill as a phician. I have already received maney applications [for treatment]. in our present Situation I think it pardonable to continue this deception for they will not give us any provisions without Compensation in merchendize, and our Stock is now reduced to a mear handfull. we take Care to give them no article which Can possible injure them. and in maney Cases can administer & give Such Medicine & Sergical aid as will effectually restore in Simple Cases &c.2

Despite differences in spelling, there are striking similarities in the two journal entries, strongly suggesting that at some point Lewis and Clark discussed the situation before writing their accounts. In essence, they realized that with Clark’s reputation as a physician among the Nez Perce, the party could now trade medical services for food and other basic necessities, but this left them with a new moral quandary.

Lewis had indeed received some medical training from Dr. Rush, but aside from this, the two explorers had little formal medical training or experience. They were appropriately dubious of their own ability to actually treat the Nez Perce, as both used the word, “deception” to describe their treatments. Faced with this decision, the two must have agreed that they could justify their actions, or that it would be, “pardonable to continue the deception,” because they had no other way of trading for the materials that the expedition needed. They agreed that they would not offer any treatment that could possibly cause injury. Even on the outskirts of structured society, Lewis and Clark upheld one of the key values of Western medicine, as expressed in the ancient Hippocratic oath and in the twentieth century principle of nonmaleficence.

In contemporary terms, avoiding harm to patients is important, but it is not the whole story.3 Lewis and Clark deceived Nez Perce patients to serve their own ends, namely, to obtain materiel for their expedition, a clearly blameworthy act by modern standards. Modern medical knowledge may help to mitigate blame for Lewis and Clark’s deception, however, because today we understand the possible benefits of placebo effects based in trust, any potential (if unintended) harm of deceiving their Native American patients was reduced by the likely considerable benefit conferred by the patients’ trust in Clark’s putative medical expertise.4

In the early nineteenth century bigotry was an accepted part of the public discourse and slavery was legally condoned. Yet the success of the expedition depended on the diverse composition of the expeditionary group,5 noteworthy among whom were York—Clark’s slave, inherited from his father; Pierre Cruzatte—part French, part Omaha Indian; John Potts—Hessian soldier; George Drouillard—part French Canadian, part Shawnee Indian; Toussaint Charbonneau—part French Canadian, part Shoshone Indian; and Charbonneau’s wife Sacagawea, whose interpreting and guidance was critical to the expedition—Shoshone Indian. Given the diversity of this close-knit group, it is not surprising that the respect Lewis and Clark held for their Native American patients led them to worry about deceiving them to satisfy their own needs.

This episode from a formative period of American history illustrates the moral concern by white people for non-white people at that time. Clearly, Lewis also manifested the Hippocratic oath’s ethical principle of avoiding harm when faced with a moral dilemma in the geographically and morally uncharted territory west of the Mississippi River. Today the future of medicine is, like the western North American continent in 1803, unknown, but as long as we remain true to current firmly established ethical principles, and recognize when we are tempted to bend or break them out of perceived necessity, as were Lewis and Clark, but resist that temptation, we will move into the future on a solid moral foundation.

References

- Donald Jackson, Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition with Related Documents, 1783-1854, 2nd ed., 2 vols. (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1978), 1:50. See Jackson also, 1:157-58, for Clark’s 1804 compilation of Indian questions, possibly expanded by material from Dr. Caspar Wistar and Dr. Benjamin Smith Barton.

- “Journals of the Lewis & Clark Expedition.” May 5, 1806 | Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, lewisandclarkjournals.unl.edu/item/lc.jrn.1806-05-05.

- Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs. Code of Medical Ethics. Chicago: American Medical Association 2017.

- Annoni M. The Ethics of Placebo Effects in Clinical Practice and Research. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2018;139:463-484. doi: 10.1016/bs.irn.2018.07.031. Epub 2018 Aug 7. PMID: 30146058.

- Legendary Lewis and Clark Expedition Characters. Available at https://www.ndtourism.com/articles/legendary-lewis-and-clark-expedition-characters. Accessed April 13, 2021.

- Boserup B, McKenney M, Elkbuli A. Disproportionate Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Racial and Ethnic Minorities. Am Surg. 2020 Dec;86(12):1615-1622. doi: 10.1177/0003134820973356. Epub 2020 Nov 24. PMID: 33231496; PMCID: PMC7691116.

DAVID BLITZER, MD, is a cardiothoracic surgery resident at New York Presbyterian Columbia University Medical Center.

ALVISE GUARIENTO, MD, is a congenital cardiac surgeon in Padua, Italy.

ROBERT M. SADE, MD, is Distinguished University Professor of Surgery, Director of the Institute of Human Values in Health Care at the Medical University of South Carolina, and Director of the Clinical Research Ethics Program.

Leave a Reply