Pedro T. Lima

Recife, Brazil

“How would you like to die?” the professor asked without breaking eye contact.

I averted my gaze to ponder the question, but no answers came to mind. “I’ve never thought about it. I guess that I would hope to be with people I love,” I stuttered, still collecting my thoughts.

“You should figure it out,” the professor replied with a smile. “Understanding your own priorities will give you the resolve to treat your patients with the dignity they deserve during the end of their lives. Just like the person we just interviewed, not everyone can be cured.”

They were pretty words, but they fell flat on my ears. How was answering that question going to help me treat my patients? I wanted to help people, not watch them die. I was a medical student and eager to feel useful. I wanted to feel like a doctor. Those feelings had guided my decision to work in the neurosurgery department, where I would be able to watch procedures and talk with patients. Although I did not yet know it, I soon would grasp the depth of my professor’s question.

Days later I stepped into the neurosurgery department, expecting my usual routine to unfold. But on that particular day, I was greeted by chaos. The clinic schedule was especially packed, and so each student and resident would need to interview patients alone. I was caught by surprise, as this would be the first time I would interview a patient by myself. Amidst this chaos, I met Josef.

As the son of two doctors, I was well versed in the culture and mannerisms of medicine. I planned out exactly what I would do: I would lead Josef to the examination room mechanically, yet naturally; ask about the illness formally, yet friendly; examine each part of the body compassionately, yet distant. I would scribble down answers, relay them to the professor, and send the patient on his way. Maybe we would spend a few minutes together. The patient would remember a stoic, competent doctor, and I would remember a good, obedient patient.

My plan could not have been any further from reality.

Josef was a gray-haired, average-looking man. However, there was nothing average about his illness, nor the way he faced it. He had been diagnosed with glioblastoma multiforme, a deadly brain cancer with a median life expectancy of about six months. The feeling of powerlessness is immeasurable.

Yet, the man in front of me was smiling, as if he was at peace with his fate.

Josef told me that no one in his family had visited or answered his calls in weeks. His only ally was his six-year-old niece, his deceased sister’s daughter who lived with him. Josef was steps away from a coffin, but his family seemed to have already buried him. Though initially they showed compassion for his diagnosis, they had already moved on. Josef had been the sole breadwinner for his entire family, a respected father and husband. After his diagnosis, however, all that had changed. Perhaps his family was resentful that they now had to step in and contribute, maybe it was a sense of self-entitlement, or just maybe it was just a particular way to grieve.

Yet, Josef now felt free of everyone and everything. He spoke in strange, definite terms. He was learning to accept both his illness and his family’s response. He understood their rage and fear, but more surprising, he held those feelings alongside his own, and planned on taking them to the grave.

The more Josef talked, the more I wanted to hear his story. It was astonishing to see a man facing his own mortality with such gentleness and forgiving those who had already left him behind.

I wanted to understand him. What doctrine or creed could one believe to face his existence gracefully like this?

He tried explaining it to me but spoke in terms I couldn’t understand. As a literature teacher, he spoke in convoluted metaphors and referenced obscure authors, while I spoke the language of scalpels and sutures. He simplified it for me: he had to be strong for his niece, the one person whose life he could impact in the brief time he had left.

I looked puzzled. Surely it could not be that simple. Josef took a deep breath and in a deep voice added, “Convictions born from feelings can only be understood if felt viscerally and self-realized. Just like one cannot be taught love, I cannot teach you how it feels to be me right now.”

We said our goodbyes as I promised to be in his following consultation.

A week went by, and Josef’s words lingered in my thoughts. They had fused with my professor’s question, hatching existential doubts in my mind about the way I envisioned my life and career. Weeks later, Josef returned for reevaluation and to discuss the histopathologic findings of his brain surgery. This time the neurosurgery resident was by my side and I felt more at ease having some backup.

Unexpectedly, Josef had brought a gift. “I don’t know how to show you the way I feel, but I figured out how to show you how I don’t want to feel,” he said, handing me a thin, well-read copy of The Metamorphosis by Franz Kafka.

He told us about living for his niece: “To have her by my side is like a dagger made of ice, stuck in my chest. It reminds me that I won’t be able to see her grow up. That pain pierces me, but at the same time, I’m thankful to be able to juxtapose my existence with hers. This numbs the pain. She truly is the anchor that grounds me to this world.”

The resident reached for the envelope with the pathology results. How long would he still have? My breathing stopped and a deafening silence filled the room. I gestured to the resident. Even though it was not my place, I felt I owed it to Josef to be the one to tell him the results. The blood rushed to my ears and my body tingled as I read: IDH wild type, the most aggressive subtype of glioblastoma. His MRI showed more tumor progression. He would only have a few more months to live.

I peeked at him, he stared at me. Like a river, he seemed to be patiently waiting as his little time left flowed through him. Not a drop of anxiety was evident on his face. Calmly, I prepared him for the next steps in treatment and he silently nodded. He stood up, thanked me, asked if there was anything else he should know, and just like that, he left.

A deep void sucked the air from the room when he left. A wave of feelings tightened my chest and itched the back of my throat, as my breathing got heavier. When I got home, I felt adrift and just stared at his gift. The Metamorphosis is the story of a lonely man who had once supported his family, but when fate began turning him into a bug, his family started to despise him. After enduring their progressive indifference and aggression, he gave up and surrendered to fate.

I wondered if Josef felt like this man-bug. But unlike Kafka’s character, Josef had found within himself a reason to keep struggling and not let his connection to this world fade. He did not want to feel like a shell of his former self, patiently watching his disease rob him of everything he loved. Maybe for Josef, Kafka had translated how it felt to be a patient at the end of life: how one can feel like a burden and alienated; how being relegated by loved ones to the land of the dying can cause despair; yet, how one can still be hopeful and happy if they find within themselves acceptance and courage to face the consequences of their existence.

I am grateful to Josef for the realization of how much growing there is left to do. My desire to help patients is the beginning but not the end of my journey as a doctor. Because of his example, I am beginning to understand what should be important for me, both as a doctor and as a person.

PEDRO T. LIMA is a fifth-year medical student at the Federal University of Pernambuco (Recife, Brazil). He researches Glioblastoma multiform zika-virus based oncolytic therapies and has papers published in innovative neurosurgical procedures and neuroanatomy. His current interests in medical humanities lie in the intersection between medicine, religion, and anthropological manifestations of suffering.

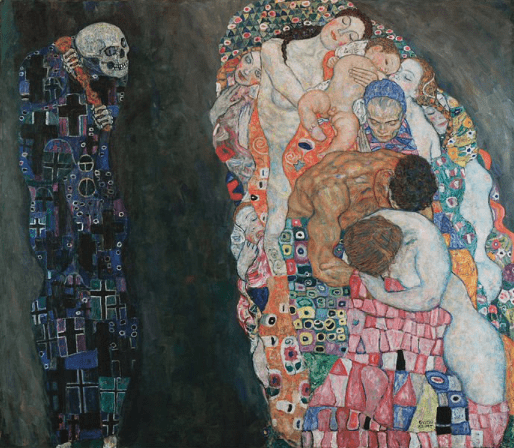

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 14, Issue 2 – Spring 2022

Leave a Reply