Mildred Wilson

Detroit, MI

“The mind is what the brain does—and more. The mind has a mind of its own. The main business of the mind is to mind its own business.”

— Edwin S. Shneidman1

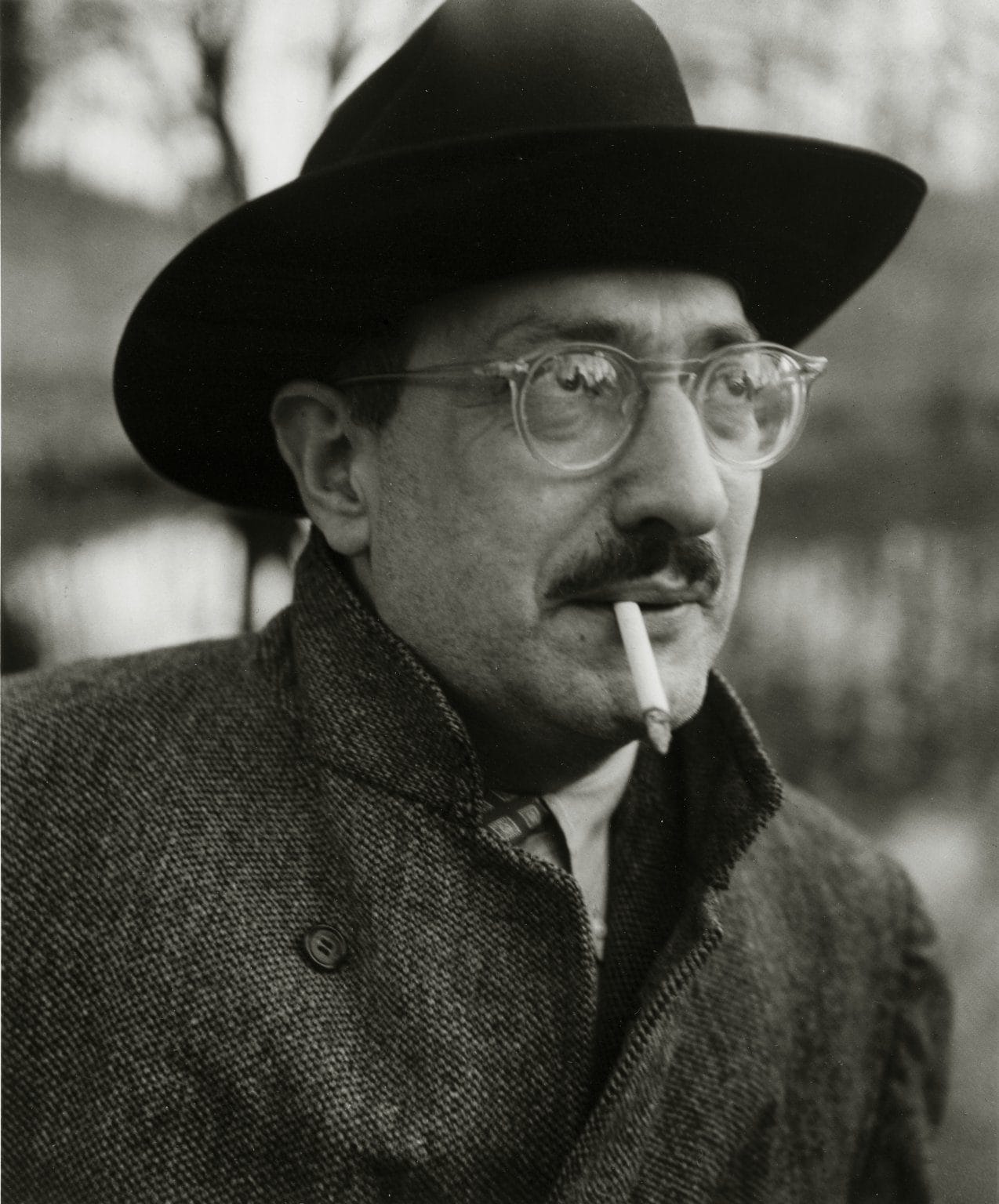

Mark Rothko was one of the most celebrated abstract expressionist painters in the twentieth century. In 1961, he opened a two-month show at the Museum of Modern Art, becoming the first living member of his generation to have a one-man show at the museum.2

In 1964, Rothko completed paintings for the Rothko Chapel, a non-denominational chapel in Houston, Texas. In 2009, National Geographic magazine ran an article, “Sacred Places of a Lifetime: 500 of the World’s Most Peaceful and Powerful Destinations.” The Rothko Chapel was a featured entry.3 In 2021, Rothko’s work continues to be relevant and influential.

Mark Rothko was born Marcus Rothkovich on September 25, 1903, in Dvinsk, a northwestern city of the Russian Empire. He was the fourth child of Yacov Rothkovich, a pharmacist, and his wife, Anna Goldin. His older siblings were Sonia, thirteen; Moses, ten; and Albert, eight.4

Rothko’s birth was a joy, but the enthusiasm was tempered by Yacov’s growing anxiety about the many organized massacres (pogroms) that were taking place against Jews.5 At age four, Rothko’s father enrolled him in the Talmud Torah. He spent intense days studying Hebrew and immersed in prayer books.6

When Rothko turned seven, his father decided to move to the United States where it would be safe. He went first and settled in Portland, Oregon. Two years later, Rothko’s brothers followed.7 In 1913, when Rothko was ten, his mother brought him and his sister. Upon arriving at Ellis Island, their names were changed from Rothkovich to Rothkowich.8

Rothko and his family settled in Little Odessa,9 a close-knit Jewish community. In 1914, a few months after Rothko arrived, his father died of colon cancer. Traditionally, the eldest son carries the heavy burden of honoring the father’s memory, but that task was placed on Rothko’s shoulders. He recited the Kaddish (Jewish prayer) daily at Shoarie Torah. He resented the task because the other members of the family were secular and he had to say the Kaddish alone. One day, he had enough and left the synagogue and never returned.10

After attending Shattuck School where he skipped from third to fifth grade, Rothko was promoted to Lincoln High School.11 He instantly found that Lincoln High School’s exclusive clubs were closed to him. He enjoyed intellectual debate, but he was not allowed to participate in their Tologeion Debating Society.12 Undeterred, he found solace in his community of Little Odessa where at the Jewish community house, he freely debated and demonstrated his literary and political creativity.

In 1921, Rothko received a scholarship to Yale.13 He felt he had done everything to fit in. He had given up the synagogue, learned English, and was prepared to rely on his intellect to construct an identity for himself in his new country.14

His two years at Yale were a disappointment. He could not live on campus during his freshman year and his scholarship was converted to a loan his sophomore year. Both years, he had to work at a series of menial jobs to pay for his education expenses.

The Yale administrators were concerned about the huge influx of Jewish students. Further, they were concerned about the impact that the Jewish students’ academic talents would have on their predominately White Anglo-Saxon Protestant classmates.15

Intellectual accomplishment and prestige had been the essential elements of Rothko’s Talmudic study.16 He realized that he was stigmatized precisely because he was bright.17 At age twenty, he left Yale for New York.

In 1923 while visiting a friend who studied figure drawing at the Art Students League, Rothko became excited and decided that art was the life for him. He took classes at the Art Students League, New School of Design, and the Educational Alliance Art School. He focused on figurative art.18

Rothko’s first professional job as an artist came in 1928. Lewis Browne, a rabbi, hired him to illustrate his book, The Graphic Bible. He signed a contract for five hundred dollars.19 The relationship between Rothko and Browne soured and Browne ended up owing Rothko fifty dollars. Rothko sued, but he lost the case and was left with nine hundred dollars in legal fees. During the legal proceedings, Browne engaged in a vicious diatribe. He attacked Rothko’s character, using terms such as “Jewish slacker” and “un-Americanized Jew.”20 Rothko was stunned. He had withstood discrimination by WASPS in high school and college, but now he was getting some of the same treatment from a rabbi! The experience left an indelible mark on him.

In the late twenties and early thirties, Rothko had two exhibitions in Portland: the Opportunity Gallery and Portland Art Museum. In 1929, he was appointed drawing instructor at the Brooklyn Jewish Center’s Academy.21

In 1932, Rothko married Edith Sachar.22 The United States was still experiencing a depression. President Franklin D. Roosevelt introduced the Works Progress Administration program (WPA). Rothko obtained employment as an easel painter and Edith taught crafts.23

During the thirties, most of the art galleries handled Old Masters.24 Local artists, like Rothko, were isolated. Rothko joined with nine other artists and formed The Ten. They exhibited the art of its members, who were all Expressionists. Critics regarded their works as having reasonless distortion.25

On February 21, 1938, Rothko became a citizen. Two years later, he changed his name to Mark Rothko.26

Rothko and Edith discovered that they were at odds philosophically. Rothko did not value worldly possessions, but Edith did. She had developed a successful jewelry business and liked the money it generated. Rothko could not understand her motivation and became bitter when she discounted his work and began to use him as a salesman for her business.27

In 1940, Rothko exhibited his work at the New York World’s Fair.28 His images focused on mythological subjects, influenced by his reading of Nietzsche’s The Birth of Tragedy.29 After the Fair, he quit painting and wrote a book, The Artists Reality.30

In 1944, he divorced Edith and married Mary Alice “Mell” Beistle in 1945.31 They had a daughter named Kate and later a son named Christopher.

In the fifties, Rothko painted rectangular regions of color, intended as “dramas” to elicit an emotional response from the viewer. He also read the works of Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung. He was interested in psychoanalytical theories concerning dreams and archetypes of a collective unconscious.32 He also stopped naming and framing his paintings, referring to them only by numbers to allow maximum interpretation.

In 1958, Rothko received a large commission from the owners of the Seagram Company for a series of paintings for the walls of its smaller dining room.33 Rothko produced thirty paintings.34 After spending a summer in Europe touring art sites, Rothko had misgivings about how his work would be viewed. He feared it would serve as mere decoration. He decided not to go through with the arrangement and returned the advance.35

In February 1965, John and Dominique de Menil commissioned him to paint a series of panels for a chapel in Houston. He was ecstatic and stated, “The magnitude, on every level of experience and meaning, of the task in which you have involved me, exceeds all of my preconceptions. And it is teaching me to extend myself beyond what I thought was possible for me. And, for this, I thank you.”36

Fourteen of Rothko’s panels were hung in the chapel.37 He was adamant as to how they should be arranged. No other painter in the history of modern art was so obsessed with the relationship between the artist and his audience.38

On February 25, 1970, Rothko’s assistant Oliver Steindecker found his thin, pale figure lying face up on the kitchen floor in a large pool of congealed blood. He wore no glasses and was clad in an undershirt, long johns, and long black socks. His arms were outstretched with deep gashes in each arm. No note was found.39

Rothko needed help and had reached out to a friend who was a psychiatrist, but he refused to treat Rothko because of their long-standing friendship. He offered to refer him but Rothko refused.40

Schneidman asserts that suicide is the result of an interior dialogue in one’s mind where the self-analysis of one’s life accepts suicide as a solution to problems.41 Two months before his death, Rothko said, “They both would be better off if I got out of their lives.”42

The “what ifs” are endless, but what if Rothko’s friend had cast his medical degrees aside and simply acted like a friend? Perhaps, the most important question might have been, “Where do you hurt?”43

End notes

- Shneidman, Edwin S., The Suicidal Mind, New York City, New York, Oxford University Press, 1996, p. 17.

- Breslin, James E. B. Mark Rothko: A Biography, Chicago, Illinois, The University of Chicago Press, 1993, p. 4.

- Rothko Chapel, www.markrothko.org/rothko-chapel. Accessed September 12, 2021.

- Cohen-Solal, Annie, Mark Rothko: Toward the Light in the Chapel, New Haven, Connecticut, Yale University Press, 2013, p. 1.

- Ibid., p. 2.

- Ibid., p. 12.

- Ibid., p. 14.

- Ibid., p. 20.

- Ibid., p. 26.

- Ibid., p. 28.

- Ibid., p. 29.

- Ibid., p. 30.

- Ibid., p. 38.

- Ibid., p. 41.

- Ibid., p. 43.

- Ibid., p. 12.

- Ibid., p. 43.

- Ibid., p. 48.

- Breslin, James E. B., Mark Rothko: A Biography, Chicago, Illinois, The University of Chicago Press, 1993, p. 67.

- Cohen-Solal, Annie, Mark Rothko: Toward the Light in the Chapel, New Haven, Connecticut, YaleUniversity Press, 2013, p. 51.

- Ibid., p. 51.

- Breslin, E. B. Mark Rothko: A Biography, Chicago, Illinois, The University of Chicago Press, 1993, p. 81.

- Ibid., p. 86.

- Cohen-Solal, Annie, Mark Rothko: Toward the Light in the Chapel, New Haven, Connecticut, Yale University Press, 2013, p. 61.

- Ibid., p. 62.

- Ibid., p. 53.

- Breslin, E. B., Mark Rothko: A Biography, Chicago, Illinois, The University of Chicago Press, 1993, p. 146.

- Cohen-Solal, Annie, Mark Rothko: Toward the Light in the Chapel, New Haven, Connecticut, Yale University Press, 2013, p. 70.

- Ibid., p. 76.

- Ibid., p. 71.

- Ibid., p. 89.

- Breslin, E. B., Mark Rothko: A Biography, Chicago, Illinois, The University of Chicago Press, 1993, p. 160.

- Cohen-Solal, Annie, Mark Rothko: Toward the Light in the Chapel, New Haven, Connecticut, Yale University Press, 2013, p. 157.

- Ibid., p. 158.

- Ibid., p. 169.

- Ibid., p. 185.

- Ibid., p. 189.

- Schama, Simon, The Power of Art, Harper Collins, New York City, N.Y, 2006, p. 420.

- Breslin, James E. B., Mark Rothko: A Biography, Chicago, Illinois, The University of Chicago Press, 1993, p. 524.

- Ibid., p. 532.

- Sneidman, Edwin S., The Suicidal Mind, New York City, N. Y., Oxford University Press, 1996, p. 15.

- Breslin, James E. B., Mark Rothko: A Biography, Chicago, Illinois, The University of Chicago Press, 1993, p. 538.

- Sneidman, Edwin S. The Suicidal Mind, New York City, New York, Oxford University Press, 1996, p. 6.

MILDRED WILSON has a Masters of Teaching in Visual Arts and a Doctorate in Curriculum Development and Administration. She is a former high school art teacher and an education analyst for the Michigan Legislative Service Bureau. She currently spends her time as a caregiver for her mother who is 101 years old and writing fiction and nonfiction.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 14, Issue 1 – Winter 2022