Frazer A. Tessema

Chicago, Illinois, United States

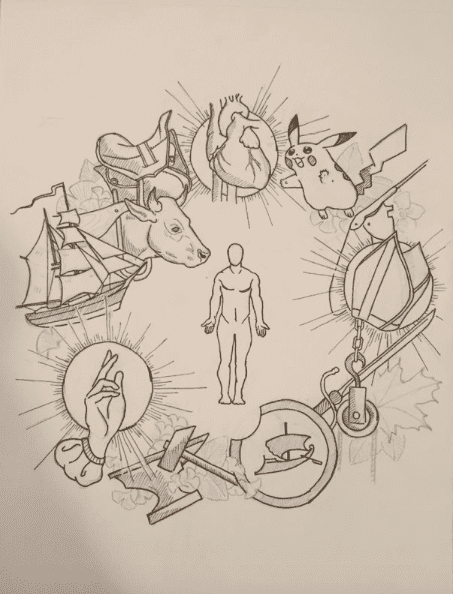

Anatomical terms often read as Latin or Greek gibberish whose main purpose is to be obscure trivia in the first-year medical school ritual called anatomy class. But a surprising trend emerges through the English translations of these archaic names: many parts of the human body are named not for the pre-modern anatomists who discovered them, but rather for the idioms, metaphors, and pop culture of their time. These culturally referential terms reveal uncanny details about the personal lives and familiarities of past scientists. From exploring the story behind these anatomical names, seemingly dull terms about the human body emerge as a time capsule of sorts, capturing the human preoccupations and socio-cultural touch points of generations past.

There are at least six categories of socio-cultural themes in anatomical naming, which include commentaries on: 1) social etiquette; 2) commerce and cultural exchange; 3) religion; 4) war and violence; 5) archaic, disproven medical thinking; and 6) the self-aware and self-referential.

1. Social etiquette

Anatomy is full of references to social customs—particularly details of long-gone rituals whose remnants linger in our bodies nonetheless. These behaviors, though mostly gone, still have modern analogs, suggesting that these terms offer insight into how our behavior and social interactions are both similar and different from the past.

The acetabulum, a divot in your hip bone, is named after a “little saucer for vinegar”—an Ancient Roman household object used for dipping bread during meals.1 Fibula, a bone in the lower leg, translates to the “clasp of a brooch” in reference to the clasp worn by Romans to hold their clothes together.1,2 Sartorius in the thigh is named for “tailors” after the cross-legged, sartorius-muscle-flexing position that French tailors commonly found themselves in as they mended clothes.1,2 The anatomical snuffbox refers to the once-common practice of “snuffing” smokeless tobacco from the divot under one’s thumb.1 The practice emerged because of its convenience (it required no instruments) and was likely used to discreetly snuff tobacco at times when the practice was socially taboo or forbidden: snuffing tobacco was once punishable by excommunication from the Catholic Church [if done in or near a church] or even execution in czarist Russia.1,3,4

2. Commerce and cultural exchange

Besides referencing social behaviors and considerations, anatomical names also discuss other anthropological phenomena like commercial trade and cultural exchange. Perhaps the clearest example is the sella turcica (“Turkish saddle”), named by a Flemish anatomist living in the Republic of Venice for a product of cultural exchange with the East.5 This name is notable for several reasons: it specifically mentions an ethnicity, it is linked to socioeconomics (these saddles were frequently an opulent, novelty gift), and the name came in an era when the Ottoman Empire tried twice to invade Europe using cavalry adorned with “Turkish saddles.”5 Thus, sella turcica is an encapsulation of many themes in cultural exchange and commerce: military anxieties, regional geopolitics, and the socioeconomics and cultural knowledge of anatomists exposed to “Turkish saddles.”

Plenty of other commerce-related imagery exists in anatomical naming. Symbols of industrial technology are common: malleus and incus (“hammer” and “anvil”); trochlea (“pulley”); and trabecula (“timber beam”).1,2,6 Images alluding to farm production and agricultural output appear frequently as well: stapes (“horse stirrup”); frenulum (“little bridle”); jugular (“yoke”—i.e., the collar worn by oxen); vomer (“ploughshare”); and falciform (“sickle-shaped”).1,2,6 Together, these etymologies call to mind an active harvest.

To anatomists, the body was a vessel of sorts, too. The transport of cargo and personnel is alluded to with several references to boats and shipping: scaphoid (“boat”); navicular (“little ship”); carina (“keel of ship”); and gubernaculum (“boat rudder”).1,2,6

3. Religion

Christian imagery also features in anatomical naming. Perhaps the most prominent example is the mitral (bicuspid) valve of the heart, named for its resemblance to miter hats worn by bishops, particularly in the Catholic and Anglican traditions.2,6 A common nerve palsy is the “Pope’s Blessing Palsy,” which occurs when compression of the median or ulnar nerve in the forearm causes the fourth and fifth digits of the hand to flex, resembling a benediction.7

The historical origin of the gesture may in fact be related to the very pathology now named in honor of a papal benediction. Modern physicians and historians speculate that the first Pope, St. Peter (c. AD 30–c. 64), may have had the ulnar variant of “Pope’s Blessing Palsy” and had to position his hand this way to wave.7 Visual evidence from early Christian paintings of St. Peter points to this theory.7 After St. Peter’s death, his papal successors copied the benediction style out of respect for the deceased Pope.7 And in a full circle of cultural influence, later anatomists named the hand gesture in honor of the Pope.

4. War and violence

Built into the naming of what keeps life animated is also ironically that which can bring it to an end: war and violence. Many anatomical terms are extended analogies in military weaponry and defense.

The anatomy of the sternum is an extended metaphor about a sword: the manubrium is its “shaft”; the gladiolus (body) is its “sword”; and the xiphoid process jutting from the gladiolus is “sword-like.”2,6 The imagery of a defensive shield also features in anatomical naming. The thyroid is named after an oval-shaped Ancient Greek shield, the “thyreos,” in reference to the organ’s protective relationship with the trachea behind it.2,6 Similarly, umbilical refers to a “knob” or “projection,” especially the ornamental knob at the center of a warrior’s shield.1,2 Anatomists may have been intimately familiar with weaponry, in part because as medical professionals they were often the caretakers who treated the wounded in war.

5. Archaic, disproven medical thinking

Holdovers from earlier eras of medical thinking that have since been disproven can also be found in modern anatomical naming. There is one notable example.

The phrenic nerve, which terminates near the diaphragm, is named for the Greek word for “mind” or “thought.”1,2 The term originates from an Ancient Greek misconception that the diaphragm was the seat of emotions and the mind.1 Perhaps the misconception arose from equating the movement of the diaphragm during sighs and crying with the actual origin of the melancholic emotions behind these gestures.

6. Self-aware and self-referential

Occasionally anatomical naming is self-aware, showing a demonstrated interest in how terms are understood and interpreted by individuals. The innominate bone of the pelvis, for example, means “not-named”—an allusion to the fact that several smaller, named bones comprise the bigger innominate bone.2,6

Other body parts are named with an awareness of anthropological cultural norms and social observations. The pudendal nerve, which runs near genitalia, means “part to be ashamed of” in reference to the prudish cultural norms of those who discovered the nerve.2,6 The temporal bone on the side of the head is named for “time” since this is where hairs first tend to go gray.1 Such naming suggests an anatomist’s awareness of how time alters human tissue and changes the substance of which we are made.

Several body parts are named in reference to other body parts, too. This self-referential naming is poetic in some ways: we can best describe parts of ourselves only in reference to other parts. The condyle prominences in the knee come from the word for “knuckle.”2,6 The genu bend of Cranial Nerve VII means “knee.”2 The crus of the diaphragm means “leg.”2,6 The mastoid process jutting from the side of the head means “breast.”2,6 The lingula on the side of the lung gets its name from the word for “tongue.”2,6 The auricles in the heart translate to “little ear.”2,6 The ventricles in the heart and the brain mean “little womb.”2,6 The renal pelvis, the inlet of the ureter into the kidney, is fittingly situated near or in the very pelvis with which it shares its name.

Conclusion

These meanings and histories are inside of us all, disguised in Latin and Greek. Together, they contain a fascinating historical record of the foibles and preoccupations of the humans who discovered the parts they describe. Anatomists had a tendency to express what is inside of us in terms of what is outside of us. And in this way, we carry within ourselves symbols of our world and worlds past.

Today, we continue to add newer symbols to our body of knowledge as recent discoveries in molecular biology are too named for socio-cultural references: patients can now have malformation of “sonic hedgehog gene” or the retinal protein “pikachurin” named after the Pokémon character, Pikachu.8,9 Our world outside, just as it has for millennia, continues to influence the names we choose for scientific, supposedly objective descriptions of ourselves. And as a result, the tapestry of socio-cultural influence in our bodies grows. Our time capsules add new keepsakes—blurring the line between who we are and what we are, one description at a time.

References

- Basic Human Anatomy – O’Rahilly, Muller, Carpenter & Swenson: Etymology with particular thanks to Jack Lyons, MD. Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth. Accessed August11, 2021, https://humananatomy.host.dartmouth.edu/BHA/public_html/resources/etymology.htm

- Online Etymological Dictionary. Dictionary. [Composed of source material from: A) Weekley E. “An Etymological Dictionary of Modern Language,” Murray J, 1921; reprint 1967, Dover Publications; B) Klein E, “A Comprehensive Etymological Dictionary of the English Language, Amsterdam: Elsevier Scientific Publishing Co., 1971; C) Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd ed., Clarendon Press, 1989; D) Barnhart RK, ed., Barnhart Dictionary of Etymology, H.W. Wilson Co., 1988; E) Holthausen F, Etymologiscches Worterbuch der Englischen Sprache, Leipzig: Bernhard Tauchnitz, 1927]. Accessed August 15, 2021, https://www.etymonline.com/

- Jack E. An Old-Fashioned Addiction. Chelsea House Publishers; 1985.

- Romanielle M. Muscovy’s Extraordinary Ban on Tobacco. In: Romaniello M, Starks T, eds. Tobacco in Russian History and Culture: From the Seventeenth Century to the Present. Routledge; 2009.

- Tekiner H, Kelestimur F. A Cultural History Of The Turkish Saddle. Turkish Studies. 2015;10(5):319-328. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.7827/TurkishStudies.8071

- Merriam Webster. Dictionary. Accessed August 16, 2021, https://www.merriam-webster.com/

- Futterman B. Analysis of the Papal Benediction Sign: The ulnar neuropathy of St. Peter. Clin Anat. Sep 2015;28(6):696-701. doi:10.1002/ca.22584

- NIH US National Library of Medicine. SHH gene: Sonic Hedgehog. https://medlineplus.gov/genetics/gene/shh/

- DiMola N. Discovered Vision Protein Named After Pikachu. https://www.nintendoworldreport.com/news/16493/discovered-vision-protein-named-after-pikachu

FRAZER A. TESSAMA is an MD Candidate at The University of Chicago Pritzker School of Medicine, where he is a Medical Student Scholar at the UChicago Bucksbaum Institute for Clinical Excellence. From 2017-2020, Frazer researched at the Harvard Medical School and Brigham & Women’s Hospital Program on Regulation, Therapeutics, and Law—publishing peer-reviewed articles on medical history and finding solutions to lowering prescription drug prices. Frazer graduated with a BA in History from Yale University in 2017.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 13, Special Issue – Fall 2021

Leave a Reply