Jack E. Riggs

Morgantown, West Virginia, United States

Donald R. Newcomer

Glendale, Arizona, United States

|

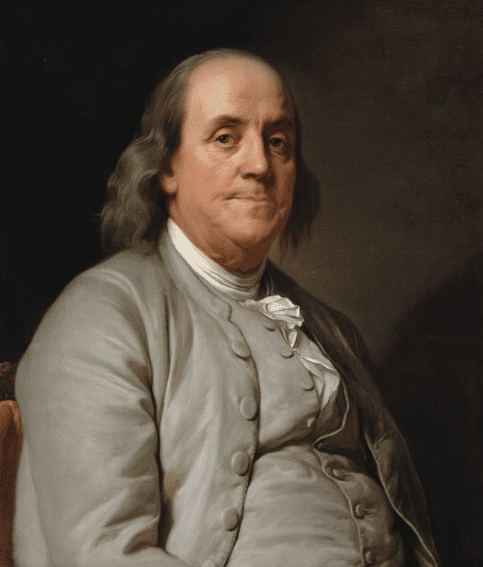

| Benjamin Franklin 1706–1790. Writer, publisher, philosopher, postmaster, scientist, diplomat. The Saying “An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure,” is commonly attributed to Franklin. Image credit: Painting by Joseph Duplessis, circa 1785. National Portrait Gallery NPG.87.43. Via Wikimedia |

Being old and lame of my Hands, and thereby uncapable of assisting my Fellow Citizens, when their Houses are on Fire; I must beg them to take in good Part the following Hints . . . In the first Place, as an Ounce of Prevention is worth a Pound of Cure

-Benjamin Franklin

The Pennsylvania Gazette, February 4, 1735

Benjamin Franklin’s famous quotes gave advice that often seemed intuitive, obvious, and true. “An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure” is certainly applicable in medicine.1 Was Franklin speaking strictly about “the protection of towns from fire”?1 His words would also seem to imply, “Your failure to prevent does not obligate me to assist in your cure.”

“Old and lame” Franklin, a founding father known for sarcasm and humor, was twenty-nine years old when he wrote that article. What would he have thought if his house burned down because of someone else’s failure to keep their chimney clean? Franklin, by his own words, was not averse to fines being levied against those who failed to prevent a catastrophe that affected others.1 The relationship between prevention and cure is far from simple, is always context dependent, and has varying applications in diverse situations.

Let us consider this in the context of crime, specifically with the example of a serial killer. Is there any rational individual who would not want to prevent future victims from a Jack-the-Ripper-style killer? These perpetrators frequently share similar life experiences thought to predispose them to becoming feared predators.2,3 However, most individuals with these life experiences do not become serial killers, and the number of active serial killers is very small compared to the number of crimes committed in the typical progression of a serial sexual killer (burglary, assault, rape, homicide). With this is mind, the city of Phoenix was sued for not preventing subsequent murder victims by the Baseline killer when it was later discovered that a piece of DNA evidence from a prior victim’s case had not been submitted for comparison in a DNA database, although other samples from the same case had been. (For more information regarding the Baseline killer, read here and here.)

As is so often the case with serial killers, the pieces of evidence seem to easily fit together in retrospect.4 But finding the killer (the proverbial needle in the haystack) from a plethora of often extraneous clues is always more difficult prospectively. The lawsuit on behalf of later victims of the Baseline killer against the city of Phoenix for failure to prevent was ultimately dismissed (1 CA-CV 15-0151.pdf (azcourts.gov)). In the situation of serial killers, prevention may not be a practical expectation. For the time being, cure (removal from society, one serial killer at a time) may be the most obtainable goal.

Covid-19 presents a different challenge with respect to the relationship between prevention and cure. Covid-19 is a viral illness without specific or definitive treatment. Cure, for the most part, means allowing the disease to run its natural course and hoping for survival without sequelae. However, a highly effective means of prevention exists in the form of vaccination.5 Who would not want to take advantage of a means of prevention that essentially equates to cure? Naturally occurring smallpox, long a human scourge, was eradicated by vaccination. However, Covid-19, it now appears, will continue to plague society and economies, in part because of vaccine hesitancy.6

Why is this so? Could it be that a counterintuitive truism is at play? If one believes that “the treatment is worse than the disease” (that is, the Covid-19 vaccination or even wearing a mask, is worse than the Covid-19 infection), then individuals will reject prevention. Where you stand on this medical, and now political, spectrum may be revealed by how you answer one question: “Am I my brother’s keeper?”

References

- Franklin B. On the protection of towns from fire. https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-02-02-0002.

- Warren JI, Hazelwood RR, Dietz PE. The sexually sadistic serial killer. J Forensic Sci 1996;41:970-974.

- Homant RJ, Kennedy DB. Understanding serial sexual murder: a biopsychological approach. In: Serial Crime, Theoretical and Practical Issues in Behavioral Profiling. Petherick W (Editor), 2nd Edition. Elsevier Academic Press, San Diego CA 2009;Chapter 13:311-349.

- Martin E, Schwarting DE, Chase RJ. Serial killer connections through cold cases. National Institute of Justice Journal https://nij.ojp.gov/topics/articles/serial-killer-connections-through-cold-cases.

- Bernal JL, Andrews N, Gower C, et al. Effectiveness of Covid-19 vaccines against the B.1.617.2 (delta) variant. N Engl J Med 2021;385:585-594.

- Machingaidze S, Wiysonge CS. Understanding COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. Nature Med 2021;27:1338-1339.

JACK E. RIGGS is a professor of neurology at West Virginia University.

DONALD R. NEWCOMER is a retired Phoenix Police Department homicide, sex crime, cold case detective who worked on the Baseline killer case.

Leave a Reply