Migel Jayasinghe

UK

This article was previously published by the author with EZineArticles in 2010. It has been edited by Hektoen International staff and republished here with the author’s permission.

|

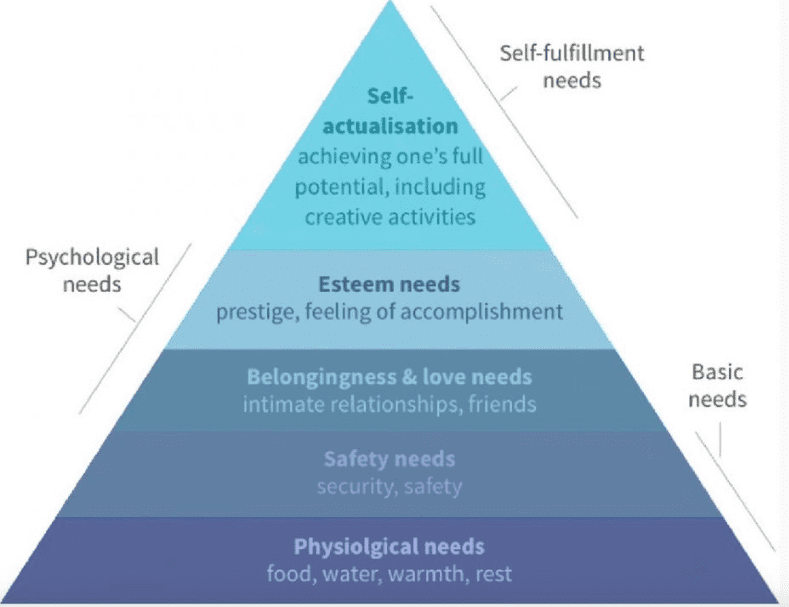

| Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. Art by Chiquo. CC BY-SA 4.0. Via Wikimedia. |

After the industrial revolution, large numbers of workers were needed in mills and factories to mass produce goods on sites that replaced agricultural and craft work in small, rural family or communal units. In the early days of industrialization in the West, slave labor or indentured labor at starvation wages, including child labor, could be harnessed at the behest of the capital-owning ruling classes.

After two world wars and a radically changed social, economic, and political environment, owners of capital could no longer treat labor as a disposable commodity. Trade unions, communism, the demand for universal education in Western and Western-style democracies, as well as the advent of worldwide markets meant that the old methods of forced, repetitive labor (“the dark satanic mills”) became a thing of the past. New disciplines like psychology, sociology, and economics sprang up. Unlike the natural sciences, theory building in the social sciences often followed practice. The resulting theories were uneven and far less cumulative, reliable, or universally valid and applicable.3 Organizational behavior and management science developed alongside advances in the social sciences.

The “carrot and stick” approach to early theories of management owe to the writings of Frederick Winslow Taylor.8 He coined the term “scientific management,” later simply called “Taylorism,” which sought to break down tasks to their simplest elements so that an assembly line robot could undertake the task without any need for thinking. All brain work was to be removed from the shop floor and handled by managers alone. This is the principle of separating conception from execution. This approach may have worked with early immigrants to the US, but its effectiveness was short-lived. However, in automated plants using very high-tech solutions for 24-hour routine work with little or no human input, the principle still applies.

Douglas McGregor7 called Taylorism and similar top-down command-and-control approaches to management of labor “Theory X” and proposed instead “Theory Y”: giving employees more autonomy and discretion at work so long as they met the overall organizational objectives. He was appealing to a more skilled and educated workforce as technology became more sophisticated over time. McGregor drew upon the work of Elton Mayo6 in what became known as the Hawthorne Studies conducted between 1927 and 1932 at the Western Electric plant in Cicero, Illinois.

Gillespie3 made a thorough review of Mayo’s Hawthorne plant experiments and questioned the whole ethos of regarding such work as objective science, although Mayo’s conclusions were widely discussed and accepted in the intervening years. Gillespie believes that there is “no purely objective scientific methodology” and that what is agreed as “scientific knowledge is manufactured and not discovered.”3 Everything that Mayo instituted in the factory, including changing the lighting and work hours, and giving more or less break time, ended with the workers producing more with each intervention. The “Hawthorne Effect” has been summarized as employees becoming more productive because they know they are being sympathetically observed. “Elton Mayo’s6 experiments showed an increase in worker productivity was produced by the psychological stimulus of being singled out, involved, and made to feel important.”2

Industrial relations have to be based on “human relations,” which was the term adopted by the Theory Y school of motivators. Their conclusions were that there was an informal group life among factory workers, and the norms they developed would affect productivity. In short, the workplace is a social system and managers ignore that fact at their own cost. Workers develop a sense of responsibility among themselves. Such an ethos was adopted by Japanese car makers, and until very recently it worked very well for them when they conquered the world car market.

A similar type of investigation was undertaken by the Tavistock Institute in London to study the work of coal miners. Trist et al9 showed that job simplification and specialization did not work under conditions of uncertainty and non-routine tasks. They advocated semi-autonomous groups. Meanwhile, there had been extensive work done outside the organizational framework that would influence motivational theory. This was the seminal work of Abraham Maslow,5 who identified a hierarchy of human needs from the lowest level of basic physiological needs up the scale to creativity and self-actualization. According to Maslow, “a need once satisfied, no longer motivates. The company relies on monetary rewards and benefits to satisfy employee’s lower-level needs. Once those needs have been satisfied, the motivation is gone . . . employees can be most productive when their work goals align with their higher-level needs.”2

Although McGregor used Maslow’s theory to bolster his Theory Y, this more complex hierarchy has been labeled Theory Z. In brief summary form and visualized as a pyramid of needs:

- Physiological (Lowest)

- Safety

- Love

- Esteem

- Self-actualization (Highest)

Another influential theory of motivation is Herzberg’s “two-factor” theory of motivation. “The theory was first drawn from an examination of events in the lives of engineers and accountants. At least 16 other investigations, using a wide variety of populations, (including some in the Communist countries) have since been completed, making the original research one of the most replicated studies in the field of job attitudes.”4 Herzberg hypothesized that the “factors involved in producing job satisfaction (and motivation) are separate from the factors that lead to job dissatisfaction . . . The opposite of job satisfaction is not job dissatisfaction, but, rather, no job satisfaction; and similarly, the opposite of job dissatisfaction is not job satisfaction, but no job dissatisfaction.”

Herzberg’s lower level factors may be listed as security, status, workplace relationships, personal life, salary, supervision, and company practices. His higher order motivators are growth, advancement, responsibility, work itself, recognition, and at the very top, a sense of achievement, which corresponds to self-actualization in Maslow’s hierarchy. All social science theorizing is contingent on many factors, so recent theories such as total quality management (TQM) and business process reengineering (BPR) account for changing current organizational concerns and deserve further exploration.

References

- Accel-Team (2010) http://www.accel-team.com/motivation/index.html . Retrieved 17/02/2010

- Envision Software, Incorporated (2009). http://www.envisionsoftware.com/articles/Theory_X.html . Retrieved 18/02/2010.

- Gillespie, R. (1993) Manufacturing Knowledge: A History of the Hawthorne Effect (Studies in Economic History and Policy: USA in the Twentieth Century). Cambridge University Press.

- Herzberg, F. (1968) One More Time: How Do You Motivate Employees? Harvard Business Review; January 2003.

- Maslow, Abraham (1943) A Theory of Human Motivation, Psychological Review Vol, 50 # 4 pp 370-396.

- Mayo, Elton (1933) The Human Problems of an Industrial Civilization, Amazon Books.

- McGregor, Douglas (1960) The Human Side of Enterprise, New York, McGraw-Hill.

- Taylor, F.W. (1911) The Principles of Scientific Management. Harper & Brothers, N.Y.

- Trist, E.L. & Bamforth, K.W. (1951) Some Social and Psychological Consequences of the Longwall Method of Coal-Getting; Sage Social Sciences Collection.

MIGEL JAYASINGHE, BA Hons, MSc, AFBPsS, C. Psychol., emigrated to the UK in 1963, and qualified in Psychology (1971) and Occupational Psychology (1982). Starting as a research assistant at the Industrial Training Research Unit, Cambridge, he worked as an occupational psychologist with the Educational and Occupational Assessment Service in Lusaka, Zambia (1975–1978), then he was an occupational psychologist with the Manpower Service Commission (1981–1995). He established the vocational assessment and rehabilitation facility for ex-service personnel at Royal British Legion Industries (1996–2001), gained distinction from UK Life Coaching Academy (2002), and ran a workshop at the First Russian Life Coaching Conference held in St. Petersburg (November 2002).

Summer 2021 | Sections | Psychiatry & Psychology

Leave a Reply