Liam Butchart

Stony Brook, New York, United States

Samantha Rizzo

Washington DC, United States

|

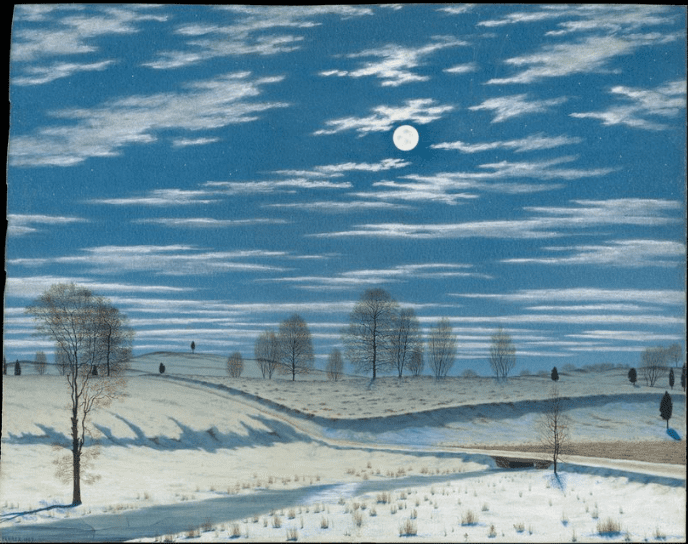

| Winter Scene in Moonlight. Henry Farrer. 1869. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. |

The COVID-19 pandemic has wrought a terrible toll upon all of us and has brought the medical system—and the providers who inhabit it—to its knees. There is a tradition in medicine, following Sir William Osler’s “Aequinimitas,” of compassionate detachment: as physicians or trainees, we must endeavor to put aside our own feelings and subsume our identities to that of the healer.1 But the COVID-19 experience is not just a physician treating a patient; for many, it has also included mourning the loss of a loved one, or supporting friends or family in their grief. If there were ever a time when the person inside of the white coat should be centered in our discourse, it is now.

In the past year, we have seen the development of a voluminous body of research on the medical aspects of COVID-19: new therapies have been developed, guidelines proposed, and clinical approaches refined. However, there has been much less consideration of how physicians may also be treated—medice, cura te ipsum. We know through experience that COVID-19 has cut many of us deeply; we are less sure about how we can address these pains. And this detracts from patient care across our medical system.

Rita Charon and the narrative medicine theorists make a strong case for why reading literature improves medical practice.2 But we suggest that literature can also be the balm for our anguish and offer insight into our own experiences. According to Aristotle, literature is mimetic—it mirrors life, in all of its beauties and trials. Sometimes, connections exist between texts and our existence that are evident, while others are more subtle. But always, if we pause to engage deeply with a text, we can find value in the way that art forces us to reflect on our shared narratives to find comfort and even healing. One such short story is Jack London’s “To Build a Fire” (1908).3

“To Build a Fire” concerns an anonymous man in the Yukon, a “newcomer in the land,” who chooses to hike in subzero temperatures, tempting fate and nature that he will make it to camp before succumbing to the biting cold. However, when viewed through the lens of our current epoch, we can appreciate a deep similarity with our experiences of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The story’s main character knows abstractly the dangers of the Yukon winter, but laughs at the old man at Sulphur Springs who urges caution. The protagonist is sure that he will return to camp by six o’clock to see the boys; accompanied by his dog, he feels prepared for nature’s onslaught. But as he intrudes on the pristine beauty around him, his reverie is shattered: first by his own lack of common sense—he forgets that he must warm himself to eat—and then by the uncaring world, as he crashes through the ice and must stop to build a fire.

After this, the dynamic between the man and nature becomes more bellicose. The man attempts, increasingly frantically, to light his fire. His first attempt is extinguished by the undisturbed snow; his subsequent efforts are stymied by the oppressive cold, which freezes his hands. He can no longer compel warmth from nature. Ultimately, the man runs, panic-stricken and desperate, but collapses into the snow: his only witness is the dog, who sits “howling under the stars that leaped and danced and shone brightly in the cold sky,” until it, too, abandons him.

This story’s man-versus-nature theme illuminates our own experience with COVID-19. We are not told why the protagonist is in the Yukon; all we know is that he is investigating whether logs could be floated downriver in the spring. Like the man, we have no answer as to why we are afflicted by COVID-19. Instead, all that we can do is actively survey the world and anticipate our post-pandemic future, committing to research to lead us toward the other side.

There is an amusingly concrete connection between the text and our past year, seen when the man notes his foolishness for failing to wear a mask: “he was sorry he had not worn the sort of nose guard Bud wore when it was cold. Such a guard passed across the nose and covered the entire face.” The parallel to our own time is clear. But the folly of failing to wear his mask is just a symptom: the real tragedy of the story is the pain and loss inflicted by nature. Initially, the man’s failures suggest that he will “be likely to lose some toes.” But, as the overpowering chill envelopes him, we realize there is nothing to be done: he will die in the snow. The assumption of suffering and mortality, brought into sharp relief by COVID-19, shows that our experience runs in agonizing parallel to the man’s.

Additionally, the story makes amply clear the man’s fundamental vulnerability to the cold. The narrator explicitly states as much, but the recurring contrast between the stubborn man, who blindly trudges onward, and his dog, whose animal instincts drive it to escape the weather, emphasizes the point: we are limited, finite beings, susceptible to the world around us. This fact feels inescapable today, as we witness the suffering wrought by a virus that often renders us powerless to treat, even with all of our modern technologies.

As the pandemic drags on, many of us have found ourselves numbed to the experience, just as the man’s repeated factual assertions that “It certainly was cold” imply a striking mundanity. After so much carnage, death can become constant and unexciting. After so long sheltering and social distancing, it feels like a new normal. “To Build a Fire” suggests an inexorable submission to despair that can feel awfully prescient, and sadly familiar to many providers.

But all is not lost. London actually published an earlier version of the same story with a vastly different outcome (1902).4 Instead of inevitably succumbing to the cold, the man is invigorated by a “love of life,” and succeeds in igniting his fire. He endures significant pain as he fights the frost, but survives his ordeal and arrives back to camp. He is marked forever, but he is alive, and wiser.

So, we suggest that “To Build a Fire” can teach us hope, even in the face of immense suffering. Hope not just for society writ large, but for the physicians and other front-line medical professionals who have given of themselves for the healing of others, even at the expense of accepting emotional pain beyond what we could have imagined before the pandemic.

Yes, we can draw practical wisdom—adhering to mask mandates and learning the limits of our dominance over nature—from the text, but its deeper value lies, to borrow again from Aristotle, in its pathos. This story, and literature in general, allows providers an outlet and a way to see their pain reflected in the characters. It allows them to feel seen, to be human, beyond the tight confines of the white coat and the role they assume each day. “To Build a Fire” exemplifies the value of narrative, not just for the physician, but for the person inside. And its theme is profound: rather than despairing in our lot with COVID-19, we can continue to fight, and, when we find the light on the other side, be stronger for it.

References

- Halpern, Jodi. What is Clinical Empathy? J Gen Int Med. 2003;18:670-674.

- Charon, Rita. Narrative Medicine: A Model for Empathy, Reflection, Profession, and Trust. JAMA. 2001;286(15):1897-1902.

- London J. To Build a Fire. Century Magazine. 1908;76(4):525-534.

- London J. To Build a Fire. Youth’s Companion. 1902;76:275.

LIAM BUTCHART is a fourth-year medical student at the Renaissance School of Medicine at Stony Brook University. He is an MD/MA candidate, pursuing a master’s degree in Medical Humanities, Compassionate Care, and Bioethics in addition to his medical degree. His research interests include psychoanalysis and mental health, literary theory and analysis, and medical education.

SAMANTHA RIZZO is a second-year medical student at Georgetown University School of Medicine where she is participating in the Health Justice scholarly track. Her research interests include the prevention and management of venous thromboembolism, infertility and thrombophilia, and acute aortic syndromes.

Leave a Reply