Stephen Martin

UK

Fig 1. Well-preserved walls of Rievaulx Abbey, 1225-40. Photo © author, 2021, permission for non-commercial and academic reuse.

North Yorkshire had many wealthy monasteries with infirmaries to care for sick monks or lay brothers.1 They were founded in the twelfth century with agricultural self-funding, and were finally dissolved by King Henry VIII. Their remains pose as many questions as they answer.

The designation of abbey, priory, or friary depended on the monastic order.

Cistercian Abbeys

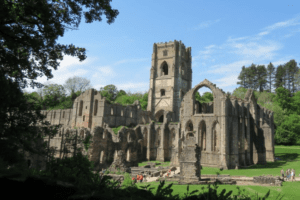

Cistercian monks selected North Yorkshire’s isolated locations. By definition, these were places of outstanding natural beauty and they remain so, framing glorious medieval architecture. To Cistercians, the physical environment was a window to God. Taming wilderness symbolized a soul’s return to God.2 They developed stricter rules than Benedictines, including the reintroduction of manual labor. Many strong Cistercian walls, though roofless, still stand to full height. (figs 1, 2)

Rievaulx Abbey Completed in the late 1100s, an aisle of rounded piers with pointed bay leaves or scallops on their capitals3 held up the vault of the now-ruined infirmary main chamber undercroft.4 (fig 3)

With its own arcaded cloister,5 (fig 4) Rievaulx shows how infirmaries replicated larger main cloisters and monks’ dormitories.6 This segregation probably embodied peace and asylum, and possibly control of putative noxious humors or the path to heaven. Rievaulx’s fifteenth-century Abbot’s lodging absorbed the infirmary as a grandiose development with lavish carvings including the Annunciation and cartoon-like carved stone friezes.

Henry VIII’s agents typically removed the roof lead and melted it into half-ton oval ingots bearing Henry’s stamp.7 After all that effort, they left one, only for Rievaulx’s roof timbers to collapse on it until modern archaeologists found it.8 We do not know if monastic hospital failure also stemmed from too little care, too little demand, or too much opulence. There is a gap in the record of the precise state of infirmaries at the dissolution, including how their functions were replaced and how far their loss was felt.

Fountains Abbey The name of this glorious abbey (fig 5) stems from natural springs.

Both the monks’ infirmary to the southeast and the southwestern lay infirmary were built in the early thirteenth century, their halls bridging right across the River Skell (fig 6) over large, multiple, barrel-vaulted water channels. (fig 7) There must have been a special reason behind the expense, time, effort, and risks of this engineering over a river. It was not from lack of space and they orientate away from the site axis to cross the meandering river at right angles.

As the theory of the second-century Greek doctor Galen rolled forward, air lifted melancholy and water dissolved irritability. Those highly psychiatric ideas may well have truth in them, in terms of relaxation, dispelling tension, and lifting mood, or the calming effect of activity in fresh air. Galen was widely taught in medieval times and healing processes were viewed as godly. Given all that, Fountains’ river culverts under the infirmary halls can be seen as continuous healing machines of Galenic science and divine intervention.

Fountains’ infirmary halls both had two aisles of pillars. The lay brothers’ black, octagonal column ruins remain. A superior design for the ordained monks included slender Nidderdale marble shafts quarried seventeen miles away, decorating varying columns of different stone. (fig 8) It must have looked stunning and suggests ideas of heavenly preparation. Nidderdale marble is a limestone, rich in crinoid fossils, picked for divine wonder. St. Cuthbert reputedly had crinoids as beads and St. Hilda was renowned for casting the Whitby serpents into the sea, creating fossilized ammonites. Surviving glazed floor tiles added to Fountains monks’ architectural privilege over lay brothers; monks were contacts to God, often sponsored to pray for souls of departed royalty, aristocrats, or saints.

The chapel was small, presumably reflecting the few patients too ill to pray in the main church.

Jervaulx Abbey The pleasure of Jervaulx today lies in the impressive remains of fine architecture. For Britain, it is an unusually romantic, overgrown, and under-conserved site, beckoning exploration. (fig 9) Parts of the infirmary hall stand to full height with fine window tracery bars in stone. (fig 10) Enough remains of the hall’s undercroft to picture its complex rib vaults. Like at Fountains, the lay brothers’ infirmary was to the southwest, and the monks’ to the southeast. Infirmary locations may have linked to sunset and sunrise as death and resurrection, besides geographical constraints. Symbolism, now forgotten, was rich in medieval times.9

Augustinian Infirmaries

Guisborough Priory (fig 11) This infirmary10 lay outside the unexcavated main cloisters, perhaps immediately south, an airy spot before the ground drops away. A rib-vaulted passage survives, which could have connected to it or supported an infirmary chapel above. It has pretty column capitals, a bit too good for a basic corridor to the nearby stores. In the early twelfth century, Adam de Brus allowed the sick of the infirmary to be acquitted of all tolls on North Sea fish caught at nearby Coatham. The Archbishop of York, William de Wickwane, inspected the priory in 1280, only a few months into his appointment. His report was damning. He criticized the monks for poor singing, drinking after dark, and malingering to gain care in the infirmary.11 The following year, Durham refused even to let Wickwayne in!

Henry VIII first announced his monastic reforms in 1537. Four years later, Prior James Cockerill of Guisborough,12 William Thirsk, penultimate Abbot of Fountains, and Adam Sedbar, Abbot of Jervaulx were all executed with more than two hundred others for protesting the dissolution a second time after the Pilgrimage of Grace. Henry appointed Hugh Whitehead, Durham’s last Abbot, as the first Cathedral Dean to reward his loyalty. However, no loyalty saved any monastic infirmaries.

St. Leonards Hospital, York This was the largest medieval public hospital in the northeast of England, with up to 240 beds, close to the River Ouse. Founded on Minster land for health care, social support, and orphanage, it was eventually run by Augustinians, with a probable woman physician, Anna Medica, in AD 1250. Its vaulted ruins and large gable window survive in the city center. With sparser population, Yorkshire lacked the outlying church-run public hospitals of County Durham.13

Kirkham Priory Like at Rievaulx, the infirmary joined the prior’s house in a separate block.

Premonstratensian Abbeys

The order condensed Augustinian and Cistercian codes. Their canons served nearby parishes.

Easby Abbey The infirmary was unusually north of the cloister. A long, high access passage survives. The infirmary had a lodging and the church was accessed by a spiral staircase.

Egglestone Abbey The infirmary’s location is not certain. The presence of a three-garderobe toilet over a twenty-foot-deep stone latrine channel suggests it was around there.14 The adjoining central room, (fig 12) now open to the sky, is over an impressive vaulted undercroft. Apparent stair ruins lead to another story, potentially the infirmary hall with staggered latrine positions over a different part of the channel.

It is a stunningly beautiful spot for an infirmary in the northwest corner, (fig 13) with wonderful views high above the River Tees and refreshing air, all very Galenic.

Franciscan Greyfriars

They had friaries in York and Richmond, the latter revealing an infirmary with its own cloister on excavation. Only the elegant perpendicular tower of Richmond remains of Yorkshire’s Franciscans.

Benedictine Abbeys

St. Mary’s Abbey, York The precinct boundary used the massive corner tower of the Roman legionary fortress of Eboracum, which still stands, with medieval upper courses. A massive timber-framed “hospitium,” of 1300-1400, also survives intact with its roof at St. Mary’s. It was not for health care, but a pilgrims’ lodging under the code of St. Benedict. Like at Guisborough, pilgrims also brought income.

One marvelous surviving artefact from this infirmary is its patinated bronze mortar (fig 14) cast by Brother William of Towthorpe, dated 1308, with his name around the base and that of the abbey around the top. Bold, blind quatrefoils contain heraldic, zodiacal, and evangelical symbols.15 It could have been used for preparations from a physic garden, but it is huge for modest quantities of medicines. It still had medical implications, because medieval doctors believed that pulverized food was easier to absorb, yielding more nutrients for the sick.

The seriousness of food was evident in the medieval inventory of kitchen equipment at nearby Sherburn leper hospital, Durham.16 It had a “lead,” implying a bronze cauldron, two brazing pots, a table, a washing or wine-making vessel, a “laver” basin for washing hands, two ale vats, and two baths that could be filled with warm water. Hygiene was prominent; though people did not know why, weak alcohol in medieval times was important anti-microbially in drinks.17

Fig 14. Bronze Mortar, 1308, St. Mary’s Abbey Infirmary, York. Top frieze shows the names of John, the Abbot, and King Edward II. De Towthorpe is immortalized on the bottom. Image courtesy of York Museums Trust, via https://yorkmuseumstrust.org.uk CC BY-SA 4

Whitby Abbey had Anglo-Saxon origins with St. Hilda and the mid-seventh-century poet Caedmon. After the conquest it revived, becoming a large monastery of the black friars around 1220. It must have had an infirmary. Not unusually, this has not been located. After all, pots broke and were discarded, clothes perished, and furniture was not left in place for archaeologists. Medieval documents leave patchy administrative details, not site plans. Whitby lacks Cistercian prettiness, but its austere sense of divine might on the clifftop above the North Sea was deliberately second to none.18

Epilogue

North Yorkshire’s monastic infirmaries are a tribute to medieval building and the sense of religious importance in housing and caring for the sick. The evidence for forgotten Galenic theory looks persuasive when you encounter air and water, again and again. Despite being ruined or overgrown, the graceful stones never fail to bowl you over. That was no coincidence in the intentions of the abbots, who must have had a sense of therapeutic esteem from architectural beauty. You can still see it all, with a bit of imagination.

End notes

- https://hekint.org/2021/05/14/the-medieval-hospitals-of-county-durham/ Their history paralleled County Durham’s infirmaries. Those considered here are not quite an exhaustive list, but for this short account we are omitting smaller or equivocal sites. The Yorkshire moorland Cistercian nunneries of Basedale and Rosedale, for example, were doubtless too small for infirmary provision. Byland Abbey developed, obliterating clear evidence of the infirmary, which probably lay in the southeast.

- Burton J, Kerr J. The Cistercians in the Middle Ages. Monastic Orders. Vol IV. Boydell and Brewer, Boydell Press, Melton, 2011, p. 56.

- The slender pointed leaves resemble rare, healing bay (laurel) leaves. Scallops still symbolize the survival of St. James, shipwrecked or begging.

- By Tudor times the vault appears to have been collapsing, because the arcade was filled in and a massive stone support was built in the east end.

- The design of a cloister as a walled area with a circumferential shelter over a path offered all-weather fresh air, protected from rain, wind, and sun, as well as peace and sunlight. They were an ancient concept; the Emperor Hadrian built several at Tivoli for exercise and impression.

- Cassidy-Welsh M. Monastic spaces and their meanings. Turnhout, 2001.

- When Little Jack Horner pulled out a plum in the nursery rhyme, it probably symbolized Henry taking the plumbium, the lead.

- Dunning G C. A lead ingot at Rievaulx Abbey. Antiquaries’ Journal, 1952, 32, pp. 199-202. At Jervaulx, Henry’s agent asked formal permission to delay transporting the lead during the winter, as the carts would sink into the mud. Reviewed in VCH, Vol 3, pp. 138-142. Many thousands of these ingots were taken overall. Once removed, ruination followed.

- A fabulous painted oak screen, which may have come from Jervaulx, is in Aysgarth church, Wensleydale, replete with Christian animal symbols. It bears the initials MH, which only fits Marmaduke Huby, Abbot of Fountains, 1495-1526, and builder of the great tower. This was previously interpreted as HM. Our measurements and estimates of choir column spaces in Rievaulx and Fountains for this article failed to prove or disprove its origin, but Huby had an earlier link to Aysgarth.

- Burton, op cit, p. 184. St. Godric the healer had visited Guisborough Priory in the twelfth century. See: Reginald. (Stevenson J, Ed.) Libellus de vita et miraculis S. Godrici, heremitae de Finchale. Surtees Society, London and Edinburgh, 1847, Vol 20, pp. 451, 454. Cistercians also made several visits to Godric (Reginald, 185, 246 & passim), revealing a network of religious medical thinking. Godric could easily have advised Aelred on Rievaulx infirmary undercroft’s bay leaves and Santiago scallop motifs after his Spanish pilgrimage. There is also evidence that the idea of Cuthbert’s crinoid beads being miraculous originated around Godric’s time, see Lane N G, Ausich W I. The Legend of St. Cuthbert’s Beads; A Palaeontological and Geological Perspective. Folklore, Vol. 112, No. 1 (April 2001), pp. 65–73.

- english-heritage.org.uk/visit/places/gisborough-priory/history/ Guisborough was earlier spelled Gisburn, surname of the Sheriff of Nottingham’s henchman, Guy of Gisburn, in Robin Hood. This was probably made up in the 1400s for a play or story, drawing on Guisborough Priory’s famous name. The Viking/Saxon root Guy-his-burn suggested a Guy at some time. No such name as Guy or its reasonable variant occurs in the well-documented local lords or the list of priors; disappointingly, Guy of Gisburn was not connected to health care.

- Smith D M, London C M (Eds). The Heads of Religious Houses: England and Wales. Vol 3, 1377-1540. CUP, Cambridge, 2001. The local college is named after Henry’s appointed successor to manage the dissolution, Prior Robert Pursglove.

- Hospitals were densest in London, which had hundreds by the fourteenth century. See: Poole A L. Medieval England. OUP, Oxford, 1958, p. 597.

- Rievaulx and Fountains infirmaries were deliberately near latrines (the reredorter) with similarly deep, washed channels. The monks did not know about fecally-transmissible infection, but they did see water balancing excess yellow bile.

- The repeated motif clockwise is a scorpion, probably zodiacal as rare in heraldry and unidentifiable in Yorkshire, lion rampant, arms of Gilling, John de Gilling being St. Mary’s Abbot 1303-1313, a winged animal, head unclear, probably the bull of St. Luke representing eponymous St. Mary’s obedience and a lion passant gardant, from York and Royal arms.

- Quoted from Sherburn archives by Robert Surtees in The History and Antiquities of the County Palatine of Durham. Nichols, Son, and Bentley, 1816-1823. Republished by E P Publishing, 1972, vol 1, p. 129.

- While medieval medicine had a completely different model from today, knowledge was often impressive. The importance of knowing anatomy and keeping instruments clean was emphasized in the 1200s (Poole, op cit, p. 597). The Persian physician Ibn Sina (Avicenna), 980-1037, was studied extensively. He laid out impressive scientific standards for using medicines. We know from Reginald of Durham (op cit, pp. 427-428) of suturing on medieval battlefields.

- Caedmon in Whitby around AD 670 put it beautifully in Anglo-Saxon, with divine and earthly double meaning: “metudæs maecti end his mōdgidanc,” viz. the might of the architect and his purpose.

Suggested further reading

- Fleming P. The Medical Aspects of the Medieval Monastery in England. Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine, Section of the History of Medicine, Nov 7, 1928, pp. 25-36.

- Page W, Ed. A History of Yorkshire North Riding. The Victoria History of the Counties of England. London, 1914.

- Pevsner N et al. The Buildings of England series. Volumes on Yorkshire The North Riding, Yorkshire West Riding, York and The East Riding. Yale University Press, earlier editions in Penguin books. Fountains was in the West Riding, but is now in North Yorkshire.

For more histories and current information on individual sites:

- historicengland.org.uk

- english-heritage.org.uk

STEPHEN MARTIN is a retired psychiatrist. He is interested in medieval history and the long eighteenth century.

Leave a Reply