Elie Najjar

St. Nottingham, United Kingdom

|

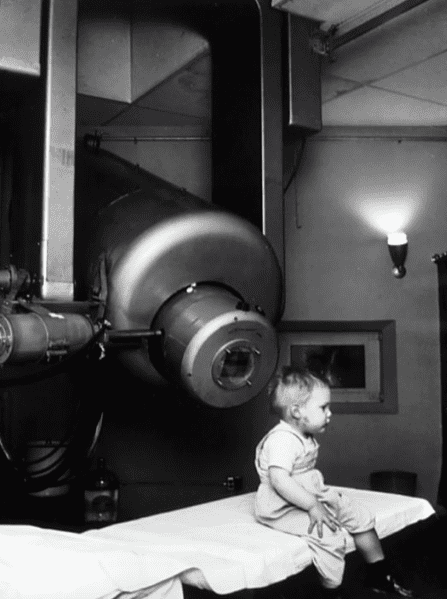

| Photo by National Cancer Institute on Unsplash |

I came to the pediatric floor to learn about medicine—the presentation, development, and resolution of diseases—but I found myself learning something that etched itself deeper into my soul. I learned about humanity and the great energy that even in the darkest of times still radiates from the faces of children.

I came to learn about sickness; instead, the children taught me about health. I came to stare death in the face, but life blossomed from them like spring. I came to learn about their maladies, but found those to be a small part of the whole. I was a blind man clinging to one withering rose while wandering in a garden of beautiful wildflowers and majestic trees.

The first lesson I learned on the pediatric floor was to overcome my ego. Helping sick children does not make one a hero or saint. Nothing compares to what they shared with me: their most private moments, tears, hopes, sadness, pursuit of better days, and even, sometimes, the last moments of life.

In the words of Khalil Gibran: “Who are you that men should render their bosom and unveil their pride, so that you may see their worth naked and their pride unabashed? See first that you yourself deserve to be a giver, and an instrument of giving.”1

When you learn to be a giver, a veil unfolds. Instead of treating a disease, you treat a patient. Through him you see all those in pain, hear all those in need. The patient no longer seems like a stranger but a brother, or even your own self. And why not? When humanity entwines us all and destiny is as blind as the night, one soul becomes all souls; one grain of sand becomes the whole desert.

“No medicine cures what happiness cannot,” wrote Gabriel Garcia Marquez.2 I learned that children smile because their eyes are still blessed with curiosity and magic. A simple idea, a small thing—a smile, a crayon and a piece of paper, a flower picked on the side of the road—expand into hope, strength, and kindness. It may even be the seed that germinates into a dream. Stories and poems, drawings, songs, the sound of laughter, friendship, and kindness are free to give and receive.

Listen well to children, but also learn the art of asking. Ask about their hopes, what they need, and how they feel. Let them express themselves any way they can. Plant dreams. Show them they are not alone in this world, not alone in their pain.

At the end of the day, many will improve and move on, but some will not. And if you feel you are going to break down, or that you have failed your beloved patients; have faith and wait. Even if you did not change the world, you have cast a stone into the waters that ripples and expands. When the world seems full of grief, pain, and death, love and life still prevail. If you do not believe me, take a walk on the pediatric floor.

Bibliography

- Gibran, Khalil. The Prophet. New York: Knopf, 1995.

- Marquez, Gabriel Garcia. Of Love and Other Demons. USA: Penguin Books, 1994.

ELIE NAJJAR comes from the land of Cedars. Professionally, Elie studied orthopedic surgery in Lebanon, worked for a while in Paris, then joined Queen’s Medical Center Spine Surgery Unit. On a more personal level, Elie is a full-time dreamer and a part-time spine surgeon. Elie hunts for dreams through literature, the faces of people, and the endless stories in the endless streets of cities. Writers like Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Amin Maalouf, and John Steinbeck among many others have shaped Elie’s life. Elie has already published several poems and won the Jane Austen Writing Competition.

Spring 2021 | Sections | Doctors, Patients, & Diseases

Leave a Reply