Howard Fischer

Uppsala, Sweden

|

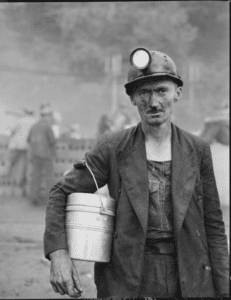

| Harry Fain, coal loader. Inland Steel Company, Wheelwright #1 & 2 Mines, Wheelwright, Floyd County, Kentucky. Russell Lee. September 1946. National Archives. Via Wikimedia. Public Domain. |

“I have written all I feel about the medical profession, its injustices, its hide-bound unscientific stubbornness . . . The horrors and inequities detailed in the story I have personally witnessed. This is not an attack against individuals but against a system.”1

–AJ Cronin

Archibald Joseph Cronin (1896–1981) was born in Scotland to a Scots Presbyterian mother and an Irish Catholic father. A good student and versatile athlete, he was awarded a scholarship at the University of Glasgow and started his medical studies in 1914. While a student during World War I, he served for two years in the Royal Navy. He got his medical degree in 1919 and started out as a general practitioner in Scotland. Later he moved to Tredegar, a mining town in southwestern Wales, where he worked long hours and saw the suffering and privation of miners’ families. Cronin managed, in his very limited spare time, to earn a diploma in public health. While in Tredegar he was appointed a medical inspector of mines and saw incompetence and corruption within and outside of the medical profession. He published articles describing the relationship between inhaled coal dust and the development of lung disease, and he was awarded an MD degree in 1925.

Dr. Cronin then turned his practice by 180 degrees. Becoming friendly in London with some wealthy Harley Street doctors, he joined them in “treating” their rich clientele. There he saw even more corruption, incompetence, and greed than in Wales.

In 1930 Cronin developed a duodenal ulcer. Treatment at the time consisted of a bland diet and strictly enforced rest. During this period of physical inactivity, Dr. Cronin became AJ Cronin, an author. His first novel, Hatter’s Castle, was published in 1931. After that he never returned to the practice of medicine. He wrote thirty-seven books, mostly novels and a few collections of short stories, the last book appearing in 1978. Nineteen films have been based on AJ Cronin’s books, as well as an equal number of television productions. During World War II he worked for the Ministry of Information. He lived in the United States for five years but spent the last twenty-five years of his life in Switzerland, where he is buried.

The Citadel2 (1937) was Cronin’s most acclaimed and best-selling novel. It is at least semi-autobiographical, the story of a newly qualified idealistic physician, Andrew Manson. He answers an advertisement for a physician to join a senior colleague in a Welsh mining village. Disappointment and deception start immediately upon his arrival. The senior colleague has been incapacitated by a stroke (even before the advertisement was placed), and Manson is expected to do the work of two, which he does for little pay. He later becomes a physician in a miners’ medical aid scheme—a sort of health maintenance organization or prepaid medical insurance. A serious problem with this type of scheme is that the doctors’ compensation is based on capitation, that is the more patients on one’s list the more money earned. This encourages destructive competition among the doctors, with insinuations and rumors about competitors’ behavior, morals, and competence.3 Moreover, having lay members (miners) on the board of a medical aid society gives them a voice in the hiring and firing of doctors. It also allows them to request “favors” from the doctors of the aid society such as work exemption excuses or medical requests for less demanding work.4

|

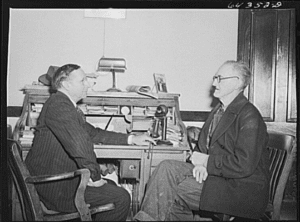

| Oran, Missouri. Farmer consulting doctor. John Vachon. 1942. Library of Congress. |

After six months as a miners’ medical society doctor, Dr. Manson finds himself in London, friendly with rich, unprincipled, and often incompetent Harley Street doctors. He makes money easily, treating pampered patients. Manson’s friend dies on the operating table because of an incompetent “society surgeon,” and Manson leaves his own practice.

Still interested in lung disease, Dr. Manson works with a scientist—who is not a physician—to treat a patient with pulmonary tuberculosis by injecting air into the pleural space surrounding the infected lung. This pneumothorax compresses the lung and lets it “rest,” while depriving the tuberculosis bacilli of oxygen. This was considered an unusual and non-traditional approach, and Manson’s numerous detractors saw the chance to cause him trouble.

It is worth noting here that the deliberate creation of a pneumothorax, one form of “collapsotherapy,” was first done in 1892 in Italy by Dr. Carlo Forlanini, and six years later in Canada.5 It became an accepted way of treating pulmonary tuberculosis by 1930.6,7,8

Manson is called before a medical board hearing, the charge being assisting a non-physician to perform a medical procedure. He eloquently defends himself, citing the valuable work of other non-physicians such as Pasteur, Ehrlich, and Metchnikoff, the latter two winners of a Nobel Prize in 1908 for research on immunity. The board decides in his favor, and he is not stricken from the medical register. He leaves to practice in the Midlands. The film The Citadel (1938) was faithful to the novel and won a number of Academy Awards.9

|

| Doorbell on doctor’s consulting rooms, Harley Street, London W1. 2011. Photo by Chemical Engineer. Via Wikimedia. CC BY-SA 3.0. |

The Citadel was a great hit with the public. Cronin, “a master of the popular novel,”10 became “a multimillionaire by today’s standards.”11 Less widely read in the UK than in the US,12 the novel received the National Book Award in 1937. A survey in the UK showed that The Citadel was thought to be “the most influential book after the Bible.”13,14 The book sold well in the Third Reich and later behind the Iron Curtain because it showed the defects in the medical capitalist system of the enemy.

Literary critics were somewhat less enthusiastic than the general public. Frederick called The Citadel “dull and graceless in style, devoid of humor . . . frequently mediocre in characterization.” He does state, however, that it is a “truer” book than Arrowsmith.15 According to O’Mahony, Cronin was “a good writer, but not a great one.”16 Late in life, Cronin accepted the judgment of writers and critics that he was “a middle-brow writer.”17

And what did Dr. Cronin’s colleagues think of The Citadel? A group of physicians tried to get the book banned. He became persona non grata “with much of the medical establishment.”18 For a doctor to expose the deficiencies of his fellow physicians was “professional treachery.”19 These doctors were, as clearly spelled out in the novel, corrupt, venal, unscientific, self-serving, fraudulent, money-grubbing, and too lazy to keep up with scientific developments. General practitioners were ignorant and used useless, outdated drugs.20 The Journal of the American Medical Association (1937) criticized the book for portraying “a not fair picture of medicine either in Great Britain or the US.”21

However, Dr. Hugh Cabot, a former medical school dean, a senior physician at the Mayo Clinic, and an early advocate of group practice wrote, “This book appears to be so important that I should be glad to believe that it would be at the disposal of every medical student and practitioner under thirty-five in this country.”22

Were there any long- or longer-term effects from the publication of The Citadel? Clearly, a flawed system was exposed. The book may have motivated young people to identify with the idealistic doctor and seek medical careers.23 The need for continuing medical education was demonstrated (and eventually adopted). Perhaps the result of the British General Election of 1945 was influenced by the book. The electorate put a Labour government in power.24 It has been suggested that the need for a National Health Service in the UK—which started in 1948—was demonstrated by conditions described in The Citadel.25,26,27 The NHS, however, was not Cronin’s idea. He was not a socialist and did not want state control of medicine. He thought that people who received free health care did not value it. Such a system would be a “paradise for hypochondriacs and malingerers.”28

The Citadel is currently used as a teaching tool in the medical humanities, both in the US29 and abroad.30 Forty-four years after the publication of The Citadel, this short obituary ran in the Lancet, January 17, 1981:

“Dr AJ Cronin, the novelist and author of The Citadel, died on Jan. 6.”

References

- Roger Jones, “AJ Cronin: novelist, GP, and visionary,” Br J Gen Pract, 65, no. 638, 2015.

- AJ Cronin, The Citadel, Boston: Little, Brown and Co., 1937.

- Fredda Katcoff, “A battle cry for medical revolution: AJ Cronin’s The Citadel, Second Chances, 2016. Secondchances636.wordpress.com.

- NA, Coalfield Web Materials, ND. agor.org.uk.

- NA, “Collapse Therapies,” Museum of Health Care at Kingston [Ont., Canada], ND. Museumofhealthcare.ca.

- John Steele, “The early use of surgical procedures in the treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis,” Calif Med, 73, no.6, 1950.

- NA, “Review: Artificial pneumothorax,” BMJ, 1, no.3615, 1930.

- Lanfranco Lazzarini, “Progress in the surgery of the lung during the past ten years,” East and West, 2, no.2, 1951.

- Peter Dans, Doctors in the movies: Boil the water and just say aah. Bloomington IL: Medi-Ed Press, 2000.

- Edward Coyle, “Development of primary care in the valleys of South East Wales – Into the 21st century,” In Health in Gwent – Annual Report, 2002.

- Jim Murdoch, ”AJ Cronin – The man who invented Dr Finlay,” The Truth about Lies, July 2011. jim-murdoch.blogspot.com.

- John Frederick, “AJ Cronin,” The English Journal, XXX, no. 9, 1941.

- Katcoff, “Battle cry.”

- Ross McKibbin, “Politics and the medical hero: AJ Cronin’s The Citadel,” The English Historical Rev, 125, no.502, 2008.

- Frederick, “AJ Cronin.”

- Seamus O’Mahony, “AJ Cronin and The Citadel: Did a work of fiction contribute to the foundation of the NHS?” J R Coll Physicians Edinb, 42, 2012.

- Murdoch, “The man who invented.”

- Ian Campbell, “AJ Cronin,” Brit J Gen Pract, 65, no 639, 2015.

- Ruth Richardson, “The art of medicine: AJ Cronin’s The Citadel,” Lancet, 387, 2016.

- O’Mahony, “The NHS.”

- Dans, “In the movies.”

- Dans, “In the movies.”

- O’Mahony, “The NHS.”

- O’Mahony, “The NHS.”

- O’Mahony, “The NHS.”

- Jones, “Novelist,GP.”

- Coalfield Web Materials.

- O’Mahony, “The NHS.”

- Jaclyn Duffin, The Citadel, LitMed: Literature, arts, medicine database. Last revised 2007. Medhum.med.nyu.edu.

- Se Won Hwang, Hun Kim, Ae Yang Kim, and Kun Hwang, “Analysis of medical students’ book reports on Cronin’s The Citadel: Would young doctors give up ideals for prestige and wealth?” Korean J Med Educ, 28, no.2, 2016.

- NA, Obituary Dr AJ Cronin, Lancet, 317, no.8212, 17 Jan 1981.

HOWARD FISCHER, MD, was a professor of pediatrics at Wayne State University School of Medicine, Detroit, MI. He considers The Citadel as having influenced his choice of medicine as a profession.

Spring 2021 | Sections | Literary Essays

Leave a Reply