Andrew Yim

Hamden, Connecticut

|

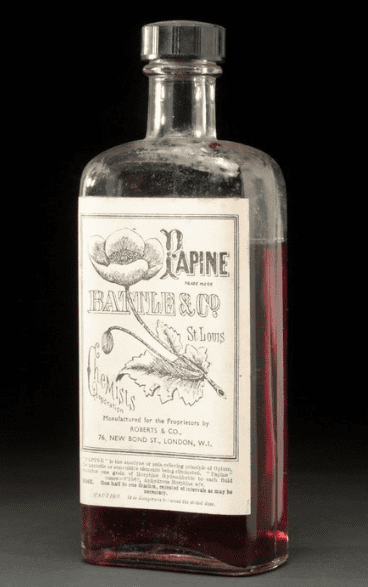

| Clear glass bottle containing ‘Papine’ brand liquid (opium and morphine hydrochloride). Science Museum Group Collection. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 |

Once a month, Ada tells me about her pain and then I write a script for oxycodone. When Ada tires of my Spanish or I of her English, we use a phone interpreter until the delays and pauses wear us down and we switch back to our pidgin Spanglish. Some days she is in tears as her arthritic, stenotic, herniated spine retracts, tightens, and then bears down on the fragile nerves like a dentist’s drill on soft enamel. Other days it relents by degrees, a point or two on our pain scale of 1 to 10.

In medicine, we love our clever scales. The number breaks complexity, all the different ways we feel and experience pain, down into a convenient, crunchable piece of data. One equals bliss, ten equals excruciating. But “10” does not tell the story of the pain. The leg fractured on descent from a high summit aches the same as the wrist inflamed by hours in the restaurant kitchen scrubbing pots. The pain cripples the mountain climber. It denies her the higher freedom and exhilaration of the summit. The pain immobilizes the wrist, prompting time off from work, financial stress, and conflict at home.

I have come to resent Ada’s pain. I know as her nurse and primary care provider, I am obligated to feel empathy and compassion. I feel powerless as she cries and asks for help. The pain now controls us both. She takes the highest dose of oxycodone per very strong recommendation of the various agencies that grant me license to prescribe. She has been to specialist after specialist and undergone two surgeries to fuse and sculpt the facets and discs of her cervical spine. I review the road she has traveled, all the referrals, medications, and therapies, and make feeble recommendations. Take a hot shower, apply a lidocaine patch, go for a walk, drink a cup of herbal tea to distract from the pain. But I resent her pain. The frustration grows without clear resolution. She senses my frustration. The tears flow again.

Pain is a biochemical construct. There is no pain, a priori. It does not exist until our mind wills it into existence. Specific nerves, the afferents, carry the message through the central nervous system. Like a well-tuned symphony, the signals range from deep and dark, basses and trombones, to high and shrill, violin and flute. The electric pulses slow or quicken through a variety of afferent nerves. Dot dot dash. Dot dash dot. Quick, sudden staccato beats signal a sharp heat at the fingertips that requires immediate action. Or we sleep under the cautious then precise surgeon’s knife. The shriek of afferent dismay is met with the indifferent silence of a neurological void.

Ada’s life revolves around the pain. It is her most constant companion. She negotiates with it each morning, asking for temporary respite to allow a walk or batch of laundry. The template of my electronic medical record prompts my questions. Does it disturb your sleep? Does it keep you from work? From walking? From sitting for extended periods of time? Yes, yes, yes, yes, she answers.

“You ask the same questions every time,” she protests. “It’s always yes.”

“I’m sorry, I have to ask.”

The computer demands data. But secretly I am thankful for this template. It shields me from long appeals for more medication, more opiate, and the full impact of her despair and frustration. Click, click, click, I check off boxes like a tinker tapping pewter back to form.

Opioids are ravishing, ravenous drugs. They seduce with promise of escape from pain and distress, then deliver near religious rapture, a biochemical eucharist that transforms pain into euphoria. The sweet flower has relieved pain and suffering since the Sumerians, some 8,000 years ago. Homer wrote that Helen, daughter of Zeus, used the bud to heal the grief of friends over the death of Odysseus. Other ancients used it to calm the colicky baby and then, in cocktail with hemlock, ease passage of the sick and infirm during euthanasia. Coleridge purportedly took its tincture with his claret, waking each morning in the sweat and tremor of withdrawal before his first hit and then lovely lines of poetry, “Here the Kubla Khan demanded a palace to be built.”

Some days, before her visits, while charting on the previous patient, I hear the rapid riffs of Caribbean Spanish as Ada chats with Flor, one of the medical assistants. They have common friends and social circles and so indulge in small talk, even gossip. Caribbean Spanish is too quick for me to catch more than a phrase here and there. But from the tone and cadence of her voice I sense that Flor’s company and words provide more comfort and solace than mine and even my drugs. “Cuidese, mi amor,” take care, my love, Flor says as she sees my approach. Ada returns the affection before her face grows tense with my entrance.

Of all the signs and symptoms of disease, few are so entwined with emotional lives, how we feel about and perceive ourselves, as pain. A cough or bout of diarrhea are usually passing nuisances, easily remedied with drug or time. The stain washes quickly. But the sensations associated with pain enter our psyche through the ancient, reptilian brain and then quickly move upward for cognition and analysis. It becomes part of the master code that guides our most important and essential actions and decisions. Sometimes the brain rewards us for the pain. But without reward and meaning, chronic pain is only chaos.

Ada takes 15 mg of oxycodone four times per day. In the old pharmacy script, the ancient apothecary, it is 15 mg 1 tab QID. Quater in die, the Latin for four times per day. Prone to misinterpretation and medical error, regulatory agencies loathe the secret script. Secret languages create close covenants and exclude the uninitiated. I would like to keep this arrangement secret, between just the pharmacist, Ada, and myself. But the Drug Enforcement Agency and Department of Public Health disagree. Each script of oxycodone posts on a national database, accessible to all prescribers and pharmacists. Our transaction is neither tryst nor stolen kiss. It is a public marriage, on display for all to view and judge. I wear the scarlet letter, O for oxycodone, on my breast.

It is just one script a month, a hundred and twenty pills. The prescription of pills that help her live in some manageable level of pain seems an unremarkable event. But a thousand and then hundred thousand prescriptions, doctors, nurse practitioners, and physician’s assistants clicking away, feeds a raging river of opioids. I am caught between this patient, her pain and frustration, my desire to somehow alleviate her suffering, and then reports of mass overdose and addiction. As I care I kill. Oxycodone QID. Quater In Die. Die. Four will die, four thousand will die, four million are dead, from oxycodone QID.

My exam is more performance than medicine. Ada flexes and extends her neck then turns it left to right to test lateral rotation. It hurts in all planes of motion, with no change from the previous month. Arthritic joints pressure inflamed nerves, which trigger cramps in stiff muscles. I grow impatient as she pleads for a higher dose. My impatience causes more guilt and then anger at both of us. The guilt surrounds, guilt at not increasing the dose, guilt at prescribing the medication, guilt at feeling resentment of the patient who triggers all this guilt. Where is the penance for all this guilt? Ok, we’ll see you in thirty days, don’t forget to stop by the lab for your urine drug screen on the way out. It is a type of benediction. Go in peace with your oxycodone, offer up your urine for analysis, and please don’t call for an early refill.

I am alone in the exam room. The ambient riot of the clinic, babies in distress at sight of nurse and needle, patients in wait who chat with friends or family, and receptionists managing the flow of calls and arrivals filters through the door as I finish her note. The computer asks me for a special code to send off the script of oxycodone, as if to launch a missile or reveal state secret. I press the button on the fob and then copy its six digits into the computer’s prompt. Should this hand have reached out to hers, to touch or reassure, to provide some moment of connection? Or perhaps pressed a spot on her neck that might provide temporary release? I code the encounter for insurance and lock the note. I try to forget her and review the next chart. That is what they teach us. Move on to the next, put the previous out of mind. Do not let it linger. Move on.

ANDREW YIM, MSN, MPH, pivoted to a career in health care after 4 years of post-collegiate travel and work in the republics of the former Soviet Union. Since 2003, he has worked in community health as a primary care nurse practitioner. Andrew also writes between breakfast and commute.

Spring 2021 | Sections | Doctors, Patients, & Diseases

Leave a Reply