Richard Spicer

Bristol, United Kingdom

Bristol Children’s Hospital

The Children’s Hospital in Bristol began as the Free Institution for Diseases of Women and Children in 1857. In 1885 it moved to a purpose-built neo-Gothic building (Fig.1) and continued to treat women and children on the same site until 1940 when bomb damage caused by the Luftwaffe reduced the capacity of the hospital, after which only children were admitted. In 1948 the word “Women” was removed from the title.1

By the 1990s the building had been extended and modified, and in 2001 the hospital moved to a site adjacent to the other major city center hospitals and is now called Bristol Royal Hospital for Children. The old building is now occupied by the adjacent University of Bristol.

Esophageal atresia

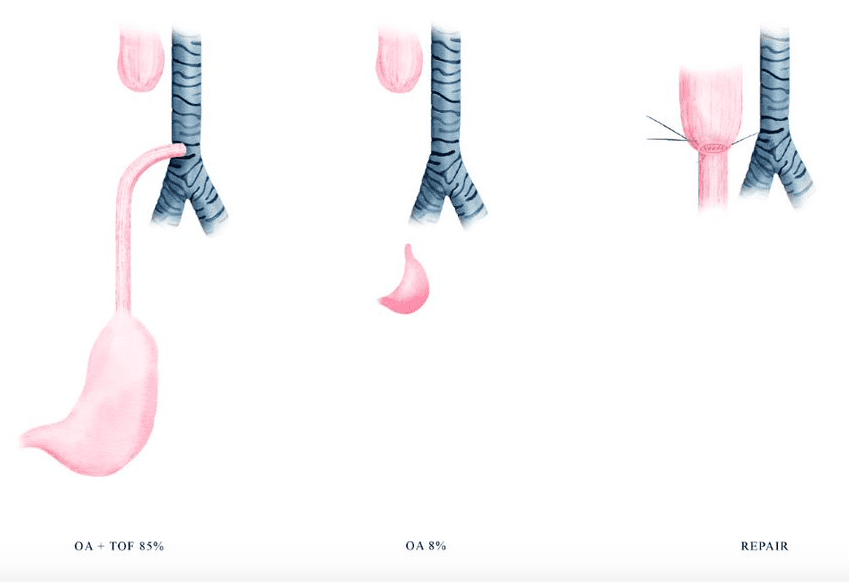

Esophageal atresia (EA) is a congenital abnormality, first described anatomically in 1670 by Durston and clinically in 1696 by Gibson.2 Babies with esophageal atresia have a blind-ending upper esophagus (Fig 2) so they cannot swallow their saliva and attempted feeding results in choking and regurgitation of feed. In 85% of cases there is a tracheoesophageal fistula (TEF), a communication between the lower esophagus and the trachea, so stomach contents reflux into the airway. This plus aspiration of feeds results in pneumonia, which is swiftly fatal if untreated.

After the initial description, more cases were described but the condition was untreatable. In 1888 Charles Steele, surgeon to the Children’s Hospital, was referred a baby twenty hours old and he described the typical history of esophageal atresia.3 He passed a sound and it encountered an impassable obstruction after five inches. He advised operation “. . . (so that) the parents might feel that every possible endeavour had been made to save their child’s life. This was agreed upon and the father willingly acceded.”

Steele operated under chloroform anesthesia. With his assistant pushing a bougie in the upper esophagus, the stomach was opened, and a bougie passed into the lower esophagus also encountered an obstruction. The distance between the tips was one and a half inches. Steele had hoped that there might be a membranous obstruction that could be perforated but this did not prove to be the case. This was the first recorded case of an attempted operation for esophageal atresia in the world.

In the early twentieth century, attempts were made to treat the babies by gastrostomies or jejunostomies, but reflux and aspiration were fatal. In the 1930s, various attempts were made to approach the esophagus by operating through the neck, abdomen, or chest, but they mostly ended in operative or postoperative mortality. Some babies survived but with significant functional impairment. It was realized that the only satisfactory treatment was going to be early repair of the esophagus by thoracotomy with closure of the fistula, and several surgeons in different centers attempted this but all resulted in early operative or postoperative deaths.2

Cameron Haight, a thoracic surgeon at the University Hospital, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA had attempted operations via the chest but had suffered the disappointment of ten successive babies dying and was uncertain whether he could go through the anguish of another failure. However, he was persuaded by his team to try again—which he did in 1941. The operation went well and the baby girl, though she suffered several postoperative complications, eventually fed, thrived, and went home. Haight had four more babies die before his second survivor in 1942. In May 1944, he presented his experience of seventeen operations with six survivors to the surgical community and thereafter surgical treatment of esophageal atresia worldwide was initiated.

Early operations were done in the United States, but eventually successful operations were carried out in most countries. The first survivor in the United Kingdom was a baby girl operated on by Dick Franklin at the Hammersmith Hospital, London, in 1947. She is alive and well at the time of writing. Overall mortality in major centers has fallen from 100% in 1940 to less than 10% by 2000. It has remained at that level since. Almost all deaths in the last twenty years have been due to associated cardiac anomalies or chromosomal disorders. Even extreme prematurity does not preclude survival.5

What have been the factors leading to the dramatic improvement in results over the last eighty years? Refinement of surgical techniques and instrumentation played some part, though in fact the main surgical principles were generally decided in the 1940s. The major factors were:

- The development of pediatric surgery as a specialty from the 1950s. The early pioneers were all adult surgeons, often working in general hospitals.

- The development of regional networks of specialist children’s hospitals, centralizing expertise.

- The development of pediatric anesthesia in the 1950s.

- Advances in neonatal intensive care and ventilation in the 1960s and 1970s.

- Availability of intravenous fluids and antibiotics.

The hospital and esophageal atresia today

My interest in this piece of medical history is partly personal; I was born three years before the first successful operation in Britain and one month before Haight first presented his experience. By the time I saw my first atresia as a junior doctor in 1970, there was a strong expectation of survival. By the time I did my first supervised atresia surgery in 1980, success was more or less guaranteed in an otherwise healthy baby. When doing these operations I always reminded my trainees and students that I (and my surgical contemporaries) would not have been around to treat esophageal atresia if we had been born with the condition.

I moved from Leeds to the Children’s Hospital in Bristol in 1992 to join the pioneering pediatric surgeon Helen Noblett6 who established the specialty in Bristol single-handedly in 1976. She was the first female pediatric surgeon in Australia and came from the unit in the Royal Children’s Hospital, Melbourne, which arguably had the best results for esophageal atresia in the world.7 Before Noblett arrived in Bristol, babies with EA had been treated by an adult surgeon. After early failures with primary repair, that adult surgeon retreated into the multi-stage operations that had been tried and abandoned by surgeons in the USA in the 1940s. Noblett’s operations in Bristol, eighty-eight years after Steele, were a great success and Bristol, as a pediatric surgical center serving a population of over four million in the Southwest of England, flourished thereafter. Bristol treats an average of twelve babies with esophageal atresia each year and has particularly good results in long-gap atresia.8

Whether one looks at the story of this condition from a local, a national, or an international perspective, it is a fascinating one. The history of the development of surgical treatment for esophageal atresia is one of the great success stories of modern surgery.

Bibliography

- Ashworth, M., The Founding of the Bristol Hospital for Sick Children, in Dissertation for the Diploma in the History of Medicine of the Society of Apothecaries1998 London.

- Myers, N., The History of Oesophageal Atresia and Tracheo-Oesophageal Fistula. Progress in Pediatric Surgery, ed. Rickham. Vol. 20. 1986, Berlin: Springer-Verlag.

- Steele, C., Case of deficient oesophagus. The Lancet, 1888. Oct.20: p. 764.

- Nakayama, D., The history of surgery for esophageal atresia. Journal of Pediatric Surgery, 2020. 55: p. 1414-1419.

- Sfeir, R., Esophageal atresia: data from a national cohort. Journal of Pediatric Surgery, 2013. 48: p. 1664-1669.

- Spicer, R. Helen Rae Noblett Obituary,British Association of Paediatric Surgeons. 2021. DOI: www.baps.org.uk/news/obituary/obituary-helen-rae-noblett/.

- Myers, N., Oesophageal atresia: the epitome of modern surgery. Ann.R. Coll. Surg., 1974. 54: p. 277-287.

- Platt, E., Pedicled jejunal interposition for long gap esophageal atresia. Journal of Pediatric surgery, 2019. 54(8): p. 1557-1562.

RICHARD D. SPICER, BA (Hons), MB BS Lond., LRCP, FRCPCH, FRCS Eng., is a retired pediatric and neonatal surgeon. He was an undergraduate at Guy’s Hospital, London, trained in pediatrics and surgery in the UK, and then worked in Cape Town and Leeds and spent one year establishing pediatric surgery in the Sultanate of Oman. He is now retired from the Bristol Royal Hospital for Children. After retirement he studied literature and humanities and is a writer.