Mateja Lekic

Phoenix, Arizona, United States

|

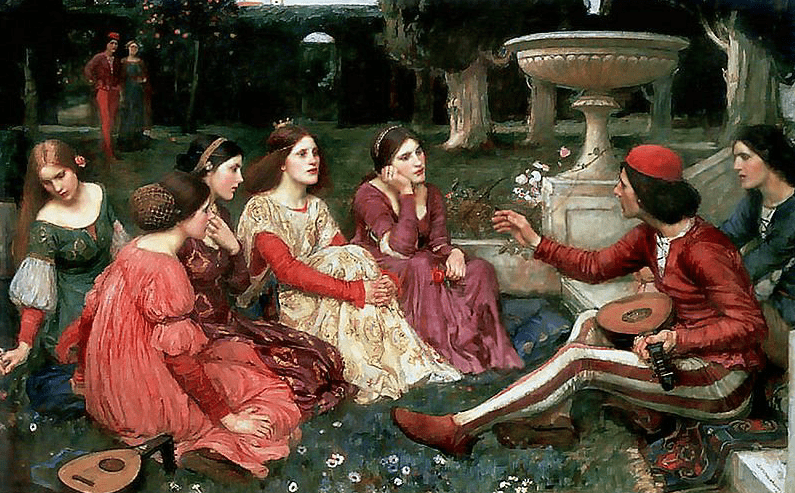

| A Tale from the Decameron, by John William Waterhouse, 1916. Source. Licensed for Public Use. |

Giovanni Boccaccio wrote the Decameron after the carnage of the bubonic plague in the late 1340s.1 Caused by the highly virulent bacterium Yersinia pestis, the bubonic plague, or Black Death, killed an estimated one quarter of the population of Europe and two-thirds of those living in Florence.2,3 What once occurred in the Middle Ages resembles in some respects today’s coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic.

In the midst of fear and terror, people responded to the outbreak with an assortment of choices. Some took all precautions, isolating in groups or withdrawing to the country. Others felt that illness and death were inevitable and indulged their cravings and desires. Yet to all, the plague was real, chronicled by Boccaccio with descriptions of the bubonic swellings, the cutaneous hemorrhages, and the dead bodies being removed from homes and left in the streets.

Today, the general population is sheltered from seeing this gruesome display in plain view. Death has been tucked away in hospitals, leading some people to question whether so many human lives have truly been lost. Meanwhile, COVID-19 patients all over the world have been suffering alone, unable to breathe and afraid, looking at the pixelated faces of their family members through video calls. Isolation is not limited to the hospitalized, as most people have been separated from family and friends. With visitor restrictions in nursing homes, many elderly have suffered physical and psychological effects.

As the pestilence of the bubonic plague spread, Boccaccio stated “. . . all the advice of physicians and all the power of medicine were profitless and unavailing. Perhaps the nature of the illness was such that it allowed no remedy. . .”1 Today, many have perished despite the many advances in modern medicine. Now overflow from morgues is being addressed by having refrigerated trucks outside hospitals; in Boccaccio’s time it was the sextons who took care of the corpses, who had the wretched job of disposing of the bodies, dropping them in open graves and trenches that often contained hundreds. Then as now, the wishes of the deceased, the funeral traditions and grief rituals have been discounted. During the current pandemic, services are often performed with few mourners physically present, but broadcasted and shared on a live stream to those at a distance. Yet at the heart of a nearly seven-hundred-year difference in time, there remains one very human impulse: to connect with one another.

As worlds are plunged into darkness and chaos, people find ways to bring joy and hope into their lives. In the Decameron, seven women and three men journey to the countryside to escape the sickness of the city and share one hundred tales over ten days. While today we are thrilled by entertainment offered through streaming services, the characters of the Decameron found amusement in their stories, which are inspirational, comic, frivolous, and tragic: characters hilariously reversing their fortunes through a series of mishaps, a wicked man mistakenly and shockingly proclaimed a saint by duping a gullible friar, vanquished love painstakingly being delivered in a golden chalice, ghosts dreadfully reliving their punishment amongst the living, and the romance of lovers secretly communicating through a crack in the wall. In our own way, we also have found more time for creativity, learning new skills, exercising, crafting, and baking. Artists have adapted by having virtual shows and drive-in concerts, and our social gatherings have evolved into video chats or masked and distanced get-togethers, allowing us to continue to share our experiences and stories.

Boccaccio states, “It is a matter of humanity to show compassion for those who suffer.”2 As a primary care physician today, I have found that the basic human instincts for empathy, affection, and concern have been constrained as sincerity through touch and facial expressions has been limited by the pandemic. The rituals of a handshake, holding a patient’s hand, or giving a hug have been removed from my daily practice. Often these actions alone would have alleviated my patients’ anxiety, apprehension, or anger. In order to slow the spread and minimize transmission of infection, clinics have limited in-person appointments and increased telemedicine. We have adapted with video-based visits, and despite their limitations, they allow for one of the important pillars of the physical exam: inspection. It is possible to evaluate, to an extent, the status of an ill patient, a simple skin rash, and identify obstacles to care. Seeing the patients’ home environments has been eye-opening: I have seen homes in disarray and patients living out of cars, allowing me to understand why compliance can be difficult. I have also met key family members, some of whom have a big impact on decision making, whom I would not otherwise have met because they work or live too far away. COVID-19 has forced doctors to grow and adapt in order to continue to provide the best care possible. These changes will allow for increased access for our patients well after the pandemic passes.

Boccaccio wrote during the most horrendous plague in European history, when suffering, sorrow, and death prevailed. The Decameron takes the reader through all of life’s emotions, disappointment, travail, and unfairness. Despite the grim surroundings, his characters find solace in telling stories, all the while practicing social distancing. Boccaccio reminds us to remain playful, optimistic, and imaginative. Physical distancing should not mean social isolation. In the end, the Decameron is a celebration of all that it means to be alive.

References

- Boccaccio, G. The Decameron 1972, 1995. Translated by G.H. McWilliam, Penguin Books,

- Boccaccio, G. The Decameron 2015. Translated by Wayne A. Rebhorn, W. W. Norton & Company.

- Ryan K.J.(Ed.). 2017. Sherris Medical Microbiology, 7e. McGraw-Hill. AccessMedicine

MATEJA LEKIC, MD, is part of the Department of Primary Care, Phoenix VA Health Care System, and the University of Arizona College of Medicine, Phoenix, Arizona.

Leave a Reply