Mariella Scerri

Victor Grech

Malta

|

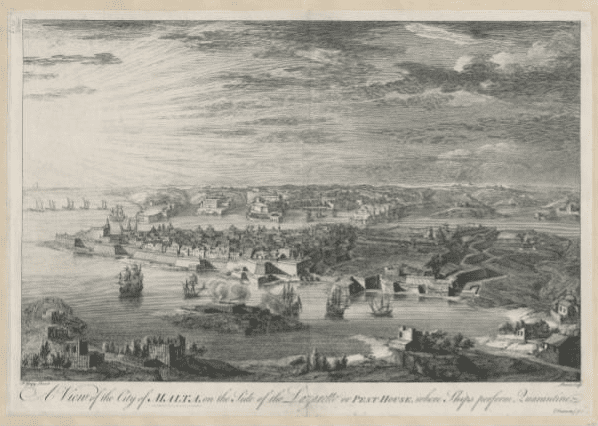

| A view of the city of Malta, on the side of the Lazaretto or pest-house, where ships perform quarantine, by Joseph Goupy, around 1740-1760. Public Domain. Source. |

Quarantine, from the Italian quaranta, meaning forty, is a centuries-old public health measure instituted to control the spread of infectious diseases by mandating isolation, sanitary cordons, and other mitigation measures.1 Though essential in preventing the spread of disease, such measures have often been controversial, as they raised “political, ethical, and socioeconomic issues and required a careful balance between public interest and individual rights.”2 The debates about “infectious disease surveillance in the years before the bacteriological revolution, are distinctly different from the years which followed” in that the germ theory transformed medical knowledge and public health policy.3

The first documented institutional response to an outbreak of a disease dates to the plague pandemic of 1347–1352, when officials began to prohibit contact with infected persons and contaminated objects. This rigid separation was initially accomplished by means of makeshift camps4 and laid the foundations for the practice of quarantine, first introduced in 1377 on the Dalmatian coast.5 The establishment of the first permanent board of health in Venice in 1486 marked the foundation of public health policy. By the nineteenth century, every major seaport in the Western world had a quarantine station where incoming ships, passengers, and cargo were inspected and could be quarantined if signs of disease were detected.6

Strict regulations during an outbreak, however, sometimes sparked a debate about the contagiousness of the disease. In the United States, recurring outbreaks of yellow fever that spread from Boston to New Orleans between 1793 and 1878 provide a classic example of such discord. When germ theory was still unknown, health officials disputed disease contagion. Some partisans fought for stricter quarantine measures, but their opponents blamed epidemics on the filthy conditions of the city and lobbied for thorough cleansing and sanitation.7

By the eighteenth century, rules about the use of quarantine had been established. During the first wave of cholera outbreaks, health officials endorsed strategies similar to those adopted in previous years.8 New lazarettos were planned at European ports, and ships were barred entry if they had “unclean licenses.”9 In cities, health authorities mandated self-isolation and quarantine. This often generated widespread resentment as it clashed with the affirmation of citizens’ rights and engendered political opposition, being seen as an abridgment of personal freedom,10 culminating in rebellions and uprisings in many European countries.11

Also questioned was the effectiveness and practicality of sanitary cordons and maritime quarantine against cholera. These measures had been successful against the plague,12 but the long duration of quarantine of forty days, which exceeded the incubation period for the plague bacillus, was seen as ineffective as a way to prevent yellow fever or cholera. Anticontagionists contested quarantine measures and argued that these past practices were useless and were damaging the economy. They also feared that quarantine would instill a false sense of security and was dangerous to public health by encouraging a laissez-faire attitude by the public.13

The debates in the International Sanitary Conferences reflected these controversies: “particularly after the opening in 1869 of the Suez Canal, which was perceived as a gate for the diseases of the Orient.”14 Despite the doubts about the benefits of quarantine, local authorities were disinclined to abandon mitigation measures, especially in times of chaos and public disorder. A historic change in quarantine regulations occurred between the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Pathogenic agents of the most feared epidemic diseases were identified, which led to separate prophylaxis strategies for cholera, plague, and yellow fever. This new knowledge activated a restructuring of international regulations, which were approved in 1903 by the 11th Sanitary Conference.15

Contact tracing was another part of a multicomponent strategy used by public health officials. In the late nineteenth century, as bacteriology emerged as a new science, it established infectious disease surveillance systems of notification, isolation, disinfection, and case finding and recruited sanitary inspectors to channel the response to outbreaks of infectious disease.16 To secure employment, these inspectors had to pass an examination testing their knowledge in four key areas: the legal aspects of public health, physics and chemistry, basic statistics, and common municipal hygiene practices.17 According to Albert Taylor’s Sanitary Inspector’s Handbook, “the sanitary inspector should visit and inspect the home of each infected person, arrange for the patient’s removal, search for possible disease sources, schedule disinfection procedures, and inquire about contacts.”18 The rigorous training expected for these inspectors did not adequately prepare them with the skills needed to obtain information from people and convince contacts of the need to quarantine. Nevertheless, sanitary inspectors took on these tasks and had to cultivate the art of persuasion on the job.19 This surveillance strategy was initially seen as an infringement on human rights and was widely rejected. However, once contact tracing became a public health tactic for a wider range of diseases, the discourse shifted towards general acceptance.

This required a delicate balancing act to treat infected persons identified by tracing. In Scotland, statutory powers were granted for the maintenance of a “reception house” for people who had been in contact with positive cases and were living in overcrowded dwellings, often without adequate basic hygiene. If necessary, they were bathed and inoculated. They were also given free lodging at the reception house for at least two weeks and released only when clear of infection.20 Such laws were not available in England, where local authorities sought to control contacts by persuasion. While many agreed to willingly go to isolation houses, reticent ones were met with threats to lock them up at home or charge them with conveying infection in a public place.21 Threats and bribery were commonplace. One health officer in London confessed that his local authority “bribed them,” arguing that “the £40 or £50 which they had expended on ‘contacts’ had saved the ratepayers some hundreds of pounds they would otherwise have had to spend on patients.”22 It is difficult to ascertain how widespread compensation payments were, or if it was limited to certain diseases, yet they are “frequently referred to in the public health literature of the time, and the national authority sanctioned them for smallpox contacts throughout the country in 1902.”23 Unfortunately, contact management was a double-edged sword. According to the law it meant that legislation targeted working-class tenement dwellers. On the other hand, it tacitly declared that uneducated and poorer classes were “a menace to the public health,” who were thought to intentionally withhold information and make misleading statements.24

Quarantine and contact tracing proved to be effective in controlling communicable diseases. However, these policies were also debated, perceived as intrusive, accompanied by an undercurrent of suspicion and distrust, and raised a variety of political, economic, social, and ethical issues.25 Indeed, the use of segregation or isolation to separate persons suspected of being infected has frequently violated the liberty of outwardly healthy persons, most often from the lower social classes. Ethnic and marginalized minority groups were stigmatized and often faced discrimination. Such a historical perspective helps us to understand the extent to which panic, connected with social stigma and prejudice, hampered public health efforts to control the spread of disease. As a result, certain modes of communication might have risked the success of “test, track and trace.”26 Leaders in countries that understood this reality created laws to quarantine contacts, and in a time before the creation of a humane welfare net, gave people compensation to acknowledge their service to the community. Indeed, this historical analysis imparts valuable lessons to be learned from past medical history.

Notes

- Matovinovic J.. “A short history of quarantine”, University of Michigan Medical Center. 1969; 35:224–8.

- Tognotti E. “Lessons from the History of Quarantine, from Plague to Influenza A”, Emergency Infectious Disease, (2013); 19.2: 254-259.

- Farre A and Rapley T. “The New Old (and Old New) Medical Model: Four Decades Navigating the Biomedical and Psychosocial Understandings of Health and Illness”, Healthcare (Basil), (2017); 5.4: 84.

- Ziegler P and Platt C. The Black Death. 2nd ed. (London: Penguin; 1998).

- Grmek MD and Buchet C. “The beginnings of maritime quarantine”, in Man, health and the sea. (Paris: Honoré Champion; 1997), pp.39–60.

- “Municipality of Venice”, Venice and plague 1348/1797, Marsilio; 1979.

- Tognotti.

- Toner JM. “The distribution and natural history of yellow fever as it has occurred at different times in the United States”, Annual report of the supervising surgeon for the fiscal year 1873. (Washington (DC): United States Marine Hospital Service; 1873). p. 78–96.

- Tognotti E. The Asiatic monster. History of cholera in Italy, (Roma-Bari: Laterza; 2000).

- Tognotti, 2013.

- Evans RJ. “Epidemics and revolutions: cholera in nineteenth-century Europe”, Past Present. (1988);120: 123–46.

- Ackerknecht EH. “Anticontagionism between 1821 and 1867”, Bulletin of Historical Medicine, (1948) ;22: 562–93.

- Tognotti, 2013.

- Huber V. “The unification of the globe by disease? The international sanitary conferences on cholera, 1851–1894”, History Journal. (2006); 49: 453–76.

- Howard-Jones N. The scientific background of the international sanitary conferences, 1851–1938, (Geneva: World Health Organization; 1975). Accessed on 28 March 2021. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/1975/14549_eng.pdf

- Mooney G. “’A Menace to the Public Health’” — Contact Tracing and the Limits of Persuasion, New England Journal of Medicine, (2020); 383.19: 1806-1808.

- Crook T. Governing systems: modernity and the making of public health in England, 1830–1910. (Oakland: University of California Press; 2016).

- Taylor A. The sanitary inspector’s handbook. 4th ed. (London: H.K. Lewis, 1905).

- Crook.

- Crook.

- Knight J. “The control of the smallpox contact”, Journal of the Royal Sanitary Institute, (1904); 25: 773-82.

- Sykes JF. “Small-pox in London: suggestions as to executive and administrative measures”, Public Health, (1901); 14: 204-17.

- Mooney.

- Mooney.

- Cetron M, and Landwirth J. “Public health and ethical considerations in planning for quarantine”, Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine. (2005); 78: 329–34.

- Mooney.

References

- Ackerknecht E.H. “Anticontagionism between 1821 and 1867”, Bulletin of Historical Medicine, (1948); 22: 562–93.

- Cetron M. and J. Landwirth. “Public health and ethical considerations in planning for quarantine”, Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine. (2005); 78: 329–34.

- Crook T. Governing systems: modernity and the making of public health in England, 1830–1910. (Oakland: University of California Press; 2016).

- Evans R.J. “Epidemics and revolutions: cholera in nineteenth-century Europe”, Past Present. (1988);120: 123–46.

- Farre Albert and Tim Rapley. “The New Old (and Old New) Medical Model: Four Decades Navigating the Biomedical and Psychosocial Understandings of Health and Illness”, Healthcare (Basil), (2017); 5.4: 84.

- Grmek M.D. and C. Buchet C. “The beginnings of maritime quarantine”, in Man, health and the sea. (Paris: Honoré Champion; 1997), pp.39–60.

- Howard-Jones N. The scientific background of the international sanitary conferences, 1851–1938, (Geneva: World Health Organization; 1975). Accessed on 28 March 2021. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/1975/14549_eng.pdf

- Huber V. “The unification of the globe by disease? The international sanitary conferences on cholera, 1851–1894”, History Journal. (2006); 49: 453–76.

- Knight J. “The control of the smallpox contact”, Journal of the Royal Sanitary Institute, (1904); 25: 773-82.

- Matovinovic J. “A short history of quarantine”, University of Michigan Medical Center. 1969; 35:224–228.

- Mooney Graham. “’A Menace to the Public Health’” — Contact Tracing and the Limits of Persuasion, New England Journal of Medicine, (2020); 383.19: 1806-1808.

- “Municipality of Venice”, Venice and plague 1348/1797, Marsilio; 1979

- Sykes J.F. “Small-pox in London: suggestions as to executive and administrative measures”, Public Health, (1901); 14: 204-17.

- Taylor A. The sanitary inspector’s handbook. 4th ed. (London: H.K. Lewis, 1905).

- Tognotti Eugenia. “Lessons from the History of Quarantine, from Plague to Influenza A”, Emergency Infectious Disease, (2013); 19.2: 254-259.

- Tognotti Eugenia. “The Asiatic monster”, in History of cholera in Italy, (Roma-Bari: Laterza; 2000).

- Toner J.M. “The distribution and natural history of yellow fever as it has occurred at different times in the United States”, Annual report of the supervising surgeon for the fiscal year 1873. (Washington (DC): United States Marine Hospital Service; 1873). p. 78–96.

- Ziegler P, and C. Platt. The Black Death. 2nd ed. (London: Penguin; 1998)

MARIELLA SCERRI, BSc, BA, PGCE, MA, is a teacher of English and a former cardiology staff nurse at Mater Dei Hospital, Malta. She is reading for a PhD in Medical Humanities at Leicester University and a member of the HUMS program at the University of Malta.

VICTOR GRECH, MD, PhD, FRCPCH, FRCP, DCH, is a consultant pediatrician to the Maltese Department of Health, and has published in pediatric cardiology, general pediatrics, and the humanities. He has completed PhDs in pediatric cardiology and English literature. He co-chairs the HUMS program at the University of Malta.

Leave a Reply