Kaitlin Kan

Villanova, Pennsylvania, United States

|

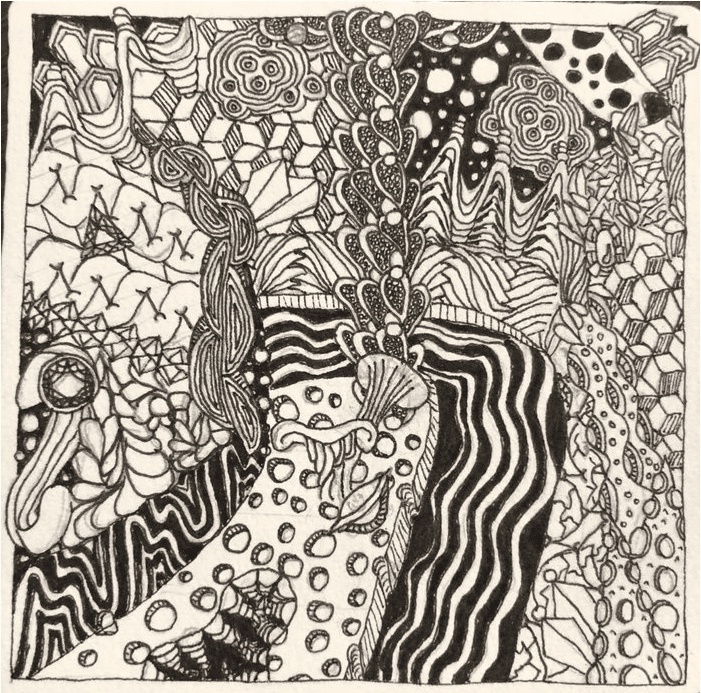

| Isle of Lethe, zentangle. Drawing by Kaitlin Kan. |

It was almost as if the neuromodulation clinic was the machine itself. The entire ward was U-shaped, with each arm housing preparation and recovery and the treatment suite nestled in the middle. Each patient was scheduled to the moment; nurses were on a constant cycle of ushering in and wheeling out like the stilted figures of a clock overlooking a European square.

I remember little from that time, but the cycles and procedures of the neuromodulation clinic are burned into my memory from sheer repetition. Specific moments are engrained too, like the chill of linoleum, the burn of fluorescent lights on sleepy eyes, and that last parting look in the mirror. It was a period of great desperation and great hope, a time in my life when I learned the power and price of sacrifice.

I was usually one of the clinic’s earliest appointments, ushered in between 7:30 and 8:00 in the morning. I would then immediately be labeled with a wristlet and thrown a clipboard with questions to test my sanity. (Who is the president? What year is it?) After my clipboard was taken by a nurse who knew me by name, she would invite me to use the bathroom. I soon came to learn that this was a euphemism for “put on a diaper,” which I learned to appreciate after wetting myself with the massive amount of liquid pumped into me through an IV while my body was under the influence of muscle relaxants. From then on, I made a habit of wearing loose-fitting clothing to accommodate the diaper.

Diapered and sufficiently sane enough to proceed, I was shown to a bed and sometimes given a warmed blanket if the nurse was in good mood. Otherwise, I simply got a sheet, and prepared for this possibility by wearing extra layers, since the neuromodulation clinic, like most clinical settings, had a distinct, sterile chill. Three or four of us were bedded in the ward, separated by blue plastic curtains we occasionally pulled back to talk to one another. After all, misery loves company. I was always the youngest person in the ward, or so I gathered. The next youngest was a man in his early thirties who was shipped over from a local psychiatric residential program. He also had tried everything else, but somehow ended up here, like me, in this place, for this treatment. I did not know him well, but I would say we shared an understanding.

Next, a nurse would come armed with tubes, needles, and saline galore. My favorite nurses were Gwen, a lanky Black woman with a bob and a voice of honey, and Julie, a neurotic Chinese fireball who walked much faster than the diminutive length of her legs suggested. Most of the nurses had their own quirks and kindnesses. I was given some Tylenol to take the edge off the post-treatment headache and a healthy dose of Zofran through the IV to ward off anesthesia-related nausea. Curiously, though, the slow trickle of Zofran into my bloodstream often slapped me with a few minutes of heavy nausea before drifting back to baseline.

Half of the treatment is waiting, anyway. Out of nerves and boredom, I would curate music playlists that oscillated between empowering and soothing. Despite being no stranger to treatment, I was still afraid every time and comforted myself with any available method. Jasha Heifetz often made the list, as did Mozart, ABBA, Ariana Grande, Jefferson Airplane, Led Zeppelin, and Beethoven, though sometimes I would follow nurses’ orders and put my phone under my bed where the rest of my belongings were stored. When my time slot neared, my bed was pushed to the narrow hallway outside the treatment room where I was left to stew in my own anxiety before the moment finally arrived. There was a sort of emptiness there, just me and my poisonous thoughts sizzling under the bars of fluorescent light. I contemplated the manner in which I was ruining myself through treatment, and the choices I had made that placed me in this nippy hallway, IV’d and diapered. Sometimes I would squirm about as I envisioned pulling the IV from the crook of my elbow and tossing it to the floor in disdain before knocking my way through the double doors of the clinic to a broken sort of freedom. Though sensible enough to stay, I nestled into the bed in apprehension, lamenting the atrophy that waited behind the door of the treatment room.

After a seeming infinity, an anesthesiologist maneuvered my bed into its appropriate dock in the treatment room, which was lined with great machines that spat out mysterious metrics. There was a good amount of business conducted between nurses, a team of anesthesiologists, and one stoic psychiatrist who perched at a laptop in the corner giving orders. The fluorescent lights on the ceiling were covered with translucent panels, which illuminated a tranquil beach scene at some tropical destination, the neuromodulation team’s attempt at patient comfort. Everyone was perfectly polite, greeting me by name, which they learned from double checking my wristband. Sometimes they even complimented me on my socks, which usually were patterned with dogs or flowers or some quirky motif.

The psychiatrist would then announce to the room: “Kaitlin Kan, bitemporal,” followed by some number I assume was the voltage. This was usually the moment of panic, the moment I knew that I could not run away. The anesthesiologist would place a stuffy oxygen mask around my nose and mouth, imploring me to breathe deeply as I began to wheeze.

“We’re going to put you to sleep, now. You might feel a little burning. Goodnight . . .” A sharp sting seared through the vein in my arm, and I would feel the movement of people behind my head. Petrified that they might begin the treatment before I was sufficiently asleep, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest style, I would scream into the mask in a frenzied attempt to let them know that I was still awake. During one of these episodes, a South-American psychiatrist with blown-out hair who looked as if she had stepped off the red carpet, caught my hand and squeezed it tightly in reassurance until the world darkened in a pendulous, hazy slumber.

I awoke to sounds of vague business on the other side. Often it was the anvil-like crush of a headache that broke the haze, though it could also be a glaze of apple juice on my lips with an order from the post-treatment nurse to drink. Activity in the post-treatment wing seemed to move slower, though perhaps that was my post-anesthetic perception. The nurses learned to take my distended bladder full of saline seriously and continued to shake me out of my daze.

While still in this blurry state, the staff would deposit me in a wheelchair and hurry me outside where my parents waited to collect me. It was an anticlimactic end to a dramatic morning, though I would repeat the cycle again in two days. The rest of the morning, needless to say, was spent in bed.

It has been a year since I completed my fifteen treatments of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), and today I sit with a tender vengeance. Shock therapy was not my first choice, but in many ways, it was promised as my only choice. I was assured that it was a safe, comfortable process. And yet, ECT hides its own pains and damages that emerge long after they bid you a final goodbye at the neuromodulation clinic.

As the treatments ended and the months marched by, memories began to slip away. There are the photographs taken at places I cannot remember, of mountains and cities I swear I have never seen, of foods I have never tasted. Moments dissipated as if they had not happened at all, and I was angry as my past became muddled and incomplete. I wanted vengeance for my moments thieved, though I failed to identify who deserved my wrath. I then turned to a cyclical self-anger, where I bitterly berated myself for suffering from a condition that necessitated such drastic and destructive measures.

And yet, even though my memories had been zapped out of me, so had the unbridled desire to die, leaving me empty for now but somehow imbued with renewed potential for another step towards a better life. I do not know how to feel the vengeance and gratitude within me, for they froth with love and hate for the damage I endured. Yet perhaps it is the shock treatment itself that set me free. I am a different woman now, resentful and beholden, wrathful and celebratory, fragmented and patched, insane and coherent, forever in search of pasts stolen and futures yet unwritten. This is the woman I have become; this is the woman the machine has made.

KAITLIN KAN studies literature and psychology at Yale University. Hailing from the suburbs of Philadelphia with Chinese ancestry, her writing draws from rich cultural ties, as well as from her extensive experiences with mental illness. She is currently working on a poetry chapbook exploring the intersections between storytelling and corporeality.

Winter 2021 | Sections | Psychiatry & Psychology

Leave a Reply