Mariella Scerri

Victor Grech

Mellieha, Malta

|

|

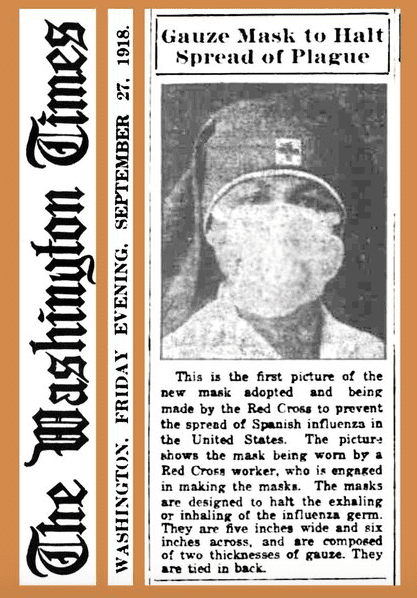

In September 1918, the Red Cross recommended two-layer gauze masks to halt the spread of “plague.” Image: Public Domain via Wikimedia. |

More than a century ago, as the 1918 influenza pandemic raged around the globe, masks of gauze and cheesecloth became the facial frontlines in the battle against the virus. However, in a volatile environment induced by a pandemic, the use of masks also stoked political division. Although medical authorities urged the wearing of masks to help slow the spread of disease, people were resistant to this simple and common-sense advice.

During the 1918 pandemic, mitigation measures such as school closures, use of masks, and no-spitting policies were instituted to try and halt the spread of disease. In Philadelphia, streetcar signs warned, “Spit Spreads Death.”1 In New York City, officials enforced no-spitting ordinances and encouraged residents to cough or sneeze into handkerchiefs—a practice that was encouraged even after the pandemic. People were also advised not to kiss “except through a handkerchief,” and wire reports spread the message around the country.2

Mask ordinances were adopted in many US states and mask wearing was considered to be a patriotic duty. In October 1918, the San Francisco Chronicle ran a public service announcement telling readers that, “The man or woman or child who will not wear a mask now is a dangerous slacker”—a reference to the type of World War I “slacker” who did not help the war effort. One sign in California even threatened, “Wear a Mask or Go to Jail.”3 Slogans such as “Wear a Mask and Save your Life” featured in San Francisco’s Chronicle newspaper, was signed by health officials, the mayor, and several other departments and organizations.4

Surgical masks made of gauze were used both by healthcare professionals and the general public. Red Cross volunteers made and distributed many of these, and newspapers—the main mode of sharing information—carried instructions for those who wanted to make a mask for themselves or donate to the troops. However, not everyone abided by the standard surgical design or material and some opted for a different design. Rules were lax in terms of what people could wear, in order to encourage mask adherence.5 While these fashionable masks made of dubious materials were not considered effective, there was also an ongoing debate among medical and scientific communities about whether multiple-ply gauze masks were effective. Detroit health commissioner J.W. Inches asserted that gauze masks were too porous and therefore limited in preventing the spread of disease. Moreover, masks needed to be worn properly for maximum effectiveness, but this was not always the case.6

Face masks became ubiquitous during this time, a vital part of disease prevention.7 However, many people still refused to wear them, claiming that government-mandated mask enforcement violated their civil liberties. An “Anti-Mask League” was even formed in San Francisco to protest the legislation.8 Men needed more convincing than did women to heed the advice of public health officials, as they associated masks with femininity.9 More worryingly, behaviors like spitting, careless coughing, and other dismissals of hygiene made men the “weak links in hygiene discipline” during the 1918 pandemic. Many of the advertisements and public health messages encouraging the public to practice good hygiene therefore depicted men and young boys.

In 1918, Americans responded to mask regulations with behaviors ranging from eager compliance, to indifferent neglect, to open defiance. The arrest of individuals for defying the mask ordinance in San Francisco received the most attention, highlighting the confrontation between policy mandates and individual actions.10 Newspaper reports claimed that defiance of the mask ordinance was justified because the masks themselves were unsafe or not healthy. Although the sources did not provide detailed information about the social status of those who resisted mask wearing, the available evidence suggests that while they probably represented a range of occupations, they were more likely to come from lower-middle social strata that included mechanics, conductors, and clerks.11 Prevention measures such as vigilant handwashing, donning facial masks, and extreme social distancing were difficult to adhere to, making it challenging for public health officials to create messages that were effective and motivational. Understanding the science of human behavior thus becomes crucial in this scenario.12

One issue related to compliance is understanding whether face masks are used for individual protection against contracting the virus or for the protection of others. The manner in which individuals in the community respond to the threat of a respiratory infection is influenced by their beliefs about the efficacy of an intervention and the perceived costs of protective behaviors.13 Behavioral change is highly contingent on the communication of risk, individual appraisal of risk, and the perceived ability to make changes.14 A central challenge to the use of masks is that many individuals view themselves as less vulnerable than others, generally underestimate health risks, or have only a limited awareness of actions that pose a health risk.15

Adherence is based on three concepts: individualism versus collectivism; trust versus fear; and willingness to obey social distance rules. Jay Van Bavel opines that some countries tend to be more individualistic,16 and therefore more likely to reject rules and ignore attempts by public health authorities to “nudge” behavior change with risk messages or appeals for altruism. In collectivist cultures, people are more likely to do what is deemed best for society. Trust and fear are also significant influences on human behavior.17 In countries with political division, people are less likely to trust advice from one side or the other and are more likely to form pro- and anti- camps. This may also undermine advice issued by public health professionals. The last and most difficult to attain is social distancing. Human beings are social animals with bodies and brains designed and wired for connection. A pandemic, in many ways, goes against our instinct to connect. Behavioral psychologist Michael Sanders argues that if everybody breaks the rules a little bit, the results are not dissimilar to many people not following the rules at all.18

Strategically, to bring about change, a new behavior must first ascend to the status of a social norm. Norms include both the perception of how a group behaves and a sense of social approval or censure for violating that conduct. Behavioral economist Syon Bhanot states that “the critical thing to lock in that norm is that you believe that other people expect you to do it.”19 Masks protect the wearers and others, hence evoking a sense of collective response. Such community-minded thinking fits with collectivist cultural norms; however, it can also serve as a powerful motivator in individualistic countries.20

Civil society and civil associations form the bedrock of democracies.21 The state’s role is merely a mechanism through which civil society can protect itself from external and internal insecurities, but it cannot function without the duties and responsibility of the individual. Margaret Thatcher’s claim that “it is our duty to look after ourselves and then also help to look after our neighbours and life is a reciprocal business […] there is no such thing as entitlement unless someone has first met an obligation”22 reverberates during a time when the whole cannot function without the duties and responsibilities of the individual. The question then remains: What can we learn from the current pandemic to strengthen our resilience in the face of ongoing adversity?

First, societies need to find renewed appreciation for freedom, law, civility, public spirit, the security of property, and family life, among other things; but do so in conjunction with “practical knowledge” and respect for traditions upon which a society is built.23 This means defending traditions, values, and all that is good in a society because they represent the core values and foundations of a society.

Secondly, there is a need to cultivate a sense of responsibility and public duty, rather than simply rely on regulations. To this end, there is an urgent need to preserve social order and institutions. As Elizabeth Braw noted, one reason why our levels of resilience have been mixed during this pandemic is the lack of preparedness, not simply by lacking materials, “but through the lack of responsibility and basic skill that arises by training in the fundamentals of preparedness and emergency response through schemes such as a voluntary national service.”24

Protracted debates during the current COVID-19 pandemic about face coverings as a medical intervention have delayed implementation of a valuable preventive tool. Now that most countries have shifted to support face coverings to reduce disease transmission, the focus needs to shift to implementation. Instead of continuing to debate technical specifications and efficacy, sociocultural framings should be explored to encourage their use. This can be done by emphasizing underlying values such as solidarity and communal safety. Drawing on knowledge of public behavior during earlier pandemics, such as the 1918 influenza outbreak, can also shed light on causes of non-adherence and dissent in facemask use. Such measures are likely to enhance the uptake of face coverings and continue to help curb the devastating impact of the pandemic.

Notes

- Becky Little. ‘Mask Slackers’ and ‘Deadly’ Spit: The 1918 Flu Campaigns to Shame People Into Following New Rules. History, (July, 2020). https://www.history.com/news/1918-pandemic-public-health-campaigns

- Little.

- Little.

- Little.

- Little.

- Little.

- K. Canales. “These surprisingly relevant vintage ads show how officials tried to convince people to wear masks after many refused during the 1918 flu pandemic”, Business Insider. July 2020. https://www.businessinsider.com/people-vintage-mask-ads-spanish-flu-1918-pandemic-2020-5

- M Tomes. “Destroyer and Teacher”: Managing the Masses During the 1918–1919 Influenza Pandemic, Public Health Rep. 2010; 125(Suppl 3): 48–62.

- Canales.

- World Health Organization. Transmission of SARS-CoV-2: implications for infection prevention precautions. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020 https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/modes-of-transmission-of-virus-causing-covid19-implications-for-ipc-precaution-recommendations

- World Health Organisation.

- World Health Organisation.

- E. Teasdale et al. The importance of coping appraisal in behavioural responses to pandemic flu, British J of Health Psych. 2020; 17: 44–59. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8287.2011.02017.x

- D.L. Floyd et al. « A Meta-Analysis of Research on Protection Motivation Theory”, J of App Psych, (2020); 30: 407–429. (doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.2000.tb02323.x).

- Floyd.

- K. Mills. “Speaking of Psychology: How the social and behavioural sciences explain our reactions to COVID-19 with Jay Van Bavel, PhD”, American Psychological Association. 2020. https://www.apa.org/research/action/speaking-of-psychology/reactions-covid-19

- Mills.

- K. Kelland and M. Revell. “Explainer: Pandemic behaviour – Why some people don’t play by the rules”, Reuters (August 2020). https://af.reuters.com/article/worldNews/idAFKCN2590MQ

- I. Merheim-Eyre. “Coronavirus, Resilience and the Limits of Rationalist Universalism”, E-International Relations, (2020).

- Merheim-Eyre.

- D. Keay. “Margaret Thatcher: Interview for Woman’s Own”, Margaret Thatcher Foundation, (1987). https://www.margaretthatcher.org/document/106689

- R. Scruton. How to be a conservative. (London: Bloomsbury; 2015).

- E. Braw. “Resilience and the Coronavirus”, RUSI, (2020). https://rusi.org/multimedia/resilience-and-coronavirus

- H. Van der Westhuizen. “Face coverings for covid-19: from medical intervention to social practice”, BMJ, (2020); 370. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m3021

References

- Braw E. “Resilience and the Coronavirus”, RUSI, (2020). https://rusi.org/multimedia/resilience-and-coronavirus

- Canales K. “These surprisingly relevant vintage ads show how officials tried to convince people to wear masks after many refused during the 1918 flu pandemic,” Business Insider. July 2020. https://www.businessinsider.com/people-vintage-mask-ads-spanish-flu-1918-pandemic-2020-5

- Floyd DL et al. “A Meta-Analysis of Research on Protection Motivation Theory”, J of App Psych, (2020); 30: 407–429. (doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.2000.tb02323.x).

- Keay D. “Margaret Thatcher: Interview for Woman’s Own”, Margaret Thatcher Foundation, (1987). https://www.margaretthatcher.org/document/106689

- Kelland K. and Revell M. “Explainer: Pandemic behaviour – Why some people don’t play by the rules”, Reuters (August 2020).

- Little Becky. ‘Mask Slackers’ and ‘Deadly’ Spit: The 1918 Flu Campaigns to Shame People Into Following New Rules. History, (July, 2020). https://www.history.com/news/1918-pandemic-public-health-campaigns

- Merheim-Eyre I. “Coronavirus, Resilience and the Limits of Rationalist Universalism”, E-International Relations, (2020).

- Mills K. “Speaking of Psychology: How the social and behavioural sciences explain our reactions to COVID-19 with Jay Van Bavel, PhD”, American Psychological Association, (2020). https://www.apa.org/research/action/speaking-of-psychology/reactions-covid-19

- R. Scruton. How to be a conservative. (London: Bloomsbury; 2015).

- Teasdale E et al. “The importance of coping appraisal in behavioural responses to pandemic flu”, British J of Health Psych, (2020); 17: 44–59. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8287.2011.02017.x

- Tomes M. “Destroyer and Teacher”: Managing the Masses During the 1918–1919 Influenza Pandemic, Public Health Rep, (2010); 125(Suppl 3): 48–62.

- Van der Westhuizen H. “Face coverings for covid-19: from medical intervention to social practice”, BMJ, (2020); 370. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m3021

- World Health Organization. “Transmission of SARS-CoV-2: implications for infection prevention precautions”, Geneva: World Health Organization, (2020). https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/modes-of-transmission-of-virus-causing-covid19-implications-for-ipc-precaution-recommendations

MARIELLA SCERRI, BSc, BA, PGCE, MA, is a teacher of English and a former cardiology staff nurse at Mater Dei Hospital, Malta. She is reading for a PhD in Medical Humanities at Leicester University and a member of the HUMS program at the University of Malta.

VICTOR GRECH, MD, PhD, FRCPCH, FRCP, DCH, is a consultant pediatrician to the Maltese Department of Health, and has published in pediatric cardiology, general pediatrics, and the humanities. He has completed PhDs in pediatric cardiology and English literature. He co-chairs the HUMS program at the University of Malta.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 13, Issue 3– Summer 2021

Winter 2021 | Sections | Covid-19

Leave a Reply