James L. Franklin

Chicago, Illinois, United States

On May 23, 1785, Benjamin Franklin wrote from Passy on the outskirts of Paris to George Whatley that “at Fourscore the three contraries that have befallen me, being subject to the Gout and the Stone, and not yet Master of all my passions.”1 It is a long letter and touchingly addressed, “Dear old Friend.” The two were exchanging thoughts on the human condition and their mortality. Whatley was a London lawyer and Franklin had contributed to his book on the Principles of Trade. He was also an officer of the Foundling Hospital of London. Whatley would die in 1791, one year after Franklin. That Franklin suffered from “the Gout and the Stone” is well known. The meaning of his reference to “not yet being Master of all my Passions” is less certain. It could refer to his project to achieve moral perfection that he set for himself as a young man and famously described in his autobiography.2 Among the thirteen virtues he sought to perfect include: “Temperance, Eat not to Dullness. Drink not to Elevation,” and “Chastity, Rarely use Venery but for Health or Offspring Never to Dullness, Weakness, or the Injury of your own or another’s Peace or Reputation.” Surprising as it may be to read that Franklin, age seventy, widowed, and the Ambassador Plenipotentiary to the Court of France for the newly constituted United States, ranked “master of all my Passions” as one of his “three contraries,” as we shall see, they were all related.

Today, gout is understood as a disorder of uric acid metabolism associated with elevated serum levels of uric acid, the final breakdown product in human purine metabolism. The precipitation of uric acid crystals in the membrane surrounding a joint (the synovium), usually at the base of the great toe, initiates an inflammatory response known as podagra (a term meaning foot-grabber) characteristic of an acute attack of gout. Increased levels of uric acid in the blood may result from increased intake of foods rich in purines (meats), conditions associated with increased cellular breakdown releasing an increased load of purines from the nuclei of cells, or a decreased renal excretion of uric acid as a result of impaired kidney function. A combination of these three factors may exist in the same person. Uric acid may be precipitated in soft tissues, resulting in painless nodules known as tophi. An increased excretion of uric acid in the urine can lead to stone formation (kidney or bladder calculi).

Franklin kept himself well informed on advances in medical science through his personal reading and extensive correspondence with leading physicians of his day both in the colonies and throughout Europe. Thomas Sydenham (1624-1689), whose writings were known to Franklin, suffered from gout and famously described the symptoms of an acute attack in a Treatise on the Gout published in 1683. During Franklin’s lifetime there were important advances in the understanding of gout. In 1679, Antoni van Leeuwenhoek (1632-1732) of Delft first described the microscopic appearance of the solid chalk-like material in a gouty tophus that “consisted of nothing but long, transparent little particles, many pointed at both ends and about 4 ‘axes. . . .” The Swedish chemist Carl Scheele (1742-1786) discovered uric acid, and another Swede, Tobern Bergman, identified the same substance in a bladder stone. It would not be until sixty years after Franklin’s death that Alfred Baring Garrod (1819-1904) would demonstrate elevated levels of uric acid in the blood of patients with gout, as well as deposits of urate in the articular cartilage of patients with gout.

The earliest indications that Franklin suffered from gout is found in a note he sent to his sister, Jane Mecom, dated “Philadelphia, November 11, 1762.” He sends regards to various relatives and mentions, “I am well except a little Touch of the Gout which my friends tell me is no Disease.” In 1767, writing from London, Franklin thanks his Philadelphia friend and physician Cadwaller Evans for advice on treatment of gout and mentions that he had suffered from “touches of that Distemper.” He also notes that Lord Chatham (William Pitt the Elder 1708–1778) was severely afflicted “thro’ the violence of the Disease, and partly by his own continual Quacking with it.” By 1770 he was writing his wife Deborah that he had been free of gout for a five-year period, but it had returned and his foot was greatly swelled, confining him for a three-week period. In another letter to Deborah on May 5, 1772, he thanks her for her advice about “putting back a Fit of the Gout.” He also notes: “Indeed I have not much Occasion to complain of the Gout, having had but two slight Fits since I last came to England.”

At the time of this letter, Franklin had already been in England since December 1764 representing the interests of the colonies in London. He did not return to America until May of 1775, his mission to preserve diplomatic relations between Great Britain and the colonies having collapsed. By then Deborah had died of a stroke on December 14, 1774, having not seen her husband for ten years.

The day after Franklin arrived in Philadelphia on May 5, 1775, he was chosen as a delegate to the Second Continental Congress. In July he was appointed Postmaster General by the Congress and in June 1776 joined Thomas Jefferson and John Adams in drafting the Declaration of Independence. We know that an attack of gout limited his participation in this process and the drafting of the declaration fell to Jefferson, though Franklin participated in revising and finalizing the document.

As a member of a Committee of Secret Correspondence of the Continental Congress, Franklin was selected by John Hancock on September 24, 1776 “to press for the immediate and explicit declaration of France in our favor, upon a suggestion that a reunion with Great Britain may be the consequence of delay.” Franklin was to cross the Atlantic and lead a delegation to secure military aid and an alliance with France that was deemed essential if America was to prevail in seeking its independence from Britain. On October 27, 1776, about to turn seventy-one and already suffering from gout and bladder stones, he set sail aboard an American warship, the Reprisal, along with his two grandsons, the seventeen-year-old Temple Franklin who would serve as his aide and secretary, and the seven-year-old Benjamin (“Benny”) Bache. Franklin believed that the experience of Europe would be a benefit to them and their presence a comfort to himself. After enduring a harrowing ocean crossing living on a diet of salt beef and plagued by “boils and rashes,” he made his entrance into Paris on December 21, 1776. His fame in France was already such that people lined the streets to get a glimpse of him. Souvenirs with an image of Franklin in his famous beaver hat flooded the shops of the capital. Franklin established the first American foreign embassy in the village of Passy, midway between Versailles and Paris near the Bois de Boulonge. The embassy was situated on the estate of the wealthy merchant Jacques-Donatien Leray de Chaumont, initially at no rent.

Though his gout had been in remission when he sailed to France, by February 1777 he reported that a fit of gout had confined him for five days. Then in 1779, just when his associates John Adams and Arthur Lee were recalled and he remained as the newly appointed minister plenipotentiary, he was initially too ill with gout and fever to travel to Versailles and present his ministerial documents to Louis XVI.

Details of Franklin’s friendship with his neighbor in Passy, Madame Brillon de Jouy, shine a light on the third of his three contraries—not yet being “master of all my Passions.” Madame Brillon was thirty-three when she first met Franklin in 1777. Her husband was twenty-four years her senior, fourteen years younger than Franklin, wealthy, and unfaithful.

Madame Brillon artfully managed a warm and flirtatious relationship with Franklin until he returned to Philadelphia in 1785. The two enjoyed each other’s company on a bi-weekly basis. In the fall of 1780 Franklin was afflicted with a severe attack of gout and she was suffering from nervous upsets, forcing them to interrupt their meetings and resort to correspondence. Madame Brillon wrote, “Le Sege et La Goutte,” a “little fable in verse in the style of Fontaine, in which she adopted toward Franklin’s disease the usual attitude of good-humored chiding.”3

“Dear Doctor” said the Gout. “You must agree

Prudence is not your strongest point. I see

You eat too much, you pass the time with dames,

Your drinking and flirtations take up time

And dissipate your powers – it’s a crime,

In stopping this I’m doing you a favor.

You should say. ‘Thanks friend. You’re a life-

Saver!’

Lifestyles that predispose one to gout were recognized in Greek and Roman antiquity. Hippocrates, credited with the earliest description of podagra, recognized that rich foods and wines had something to do with its cause. Galen attributed it to rich diets and excessive drinking, but also asserted that venery (sexual excess) might cause it. The Greeks laid gout at the foot of Aphrodite and the Romans Venus as the etymology of venery suggests. Franklin did not dispute the role of overeating and drinking but he did challenge the role of sexual activity. He pointed out that as a young man he enjoyed more favors of the fair sex and was not troubled with gout. “Hence, if the ladies of Passy had shown more of that Christian charity that I have so often recommended. . . . I should not be suffering from the Gout right now.”

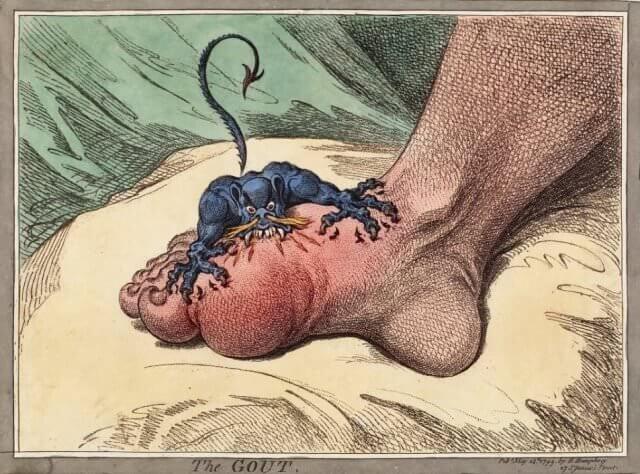

Inspired by Madame Brillon’s poem, Franklin composed a playful piece “Dialogue Between the Gout and Mr. Franklin, October 22, 1780.” With the help of a friend who corrected his French version, he sent the manuscript to Madame Brillon for her comments. The original manuscript, which still exists with her annotations, shows that she preferred his unorthodox French, finding it more pungent and more original. In this charming piece Franklin gives us a picture of his first contrary. Typical of an attack of gout, the sufferer, Mr. F, is awakened at midnight by The Gout personified as his enemy in person. The Gout makes it clear that he takes a quantity of meat and drink in excess of a man who takes no exercise. Mr. F protests, addressing his tormenter as “Madam Gout.,” making it clear he is responding to Madame Brillon’s poem (literary and visual images of “The Gout” are often satanic and gender-neutral). The Gout rebukes Mr. F for pursuing chess when opportunities for exercise in the lovely gardens and walks in “Passy, Auteuil, Montmartre or Sanvoy would be preferable,” the residences of lovely ladies in Franklin’s circle. The Gout insists that she is his physician and friend: “Is it not I who in the character of your physician, have saved you from palsy, dropsy, and apoplexy?” Franklin is invoking the belief prevalent among physicians of his day that gout afforded its victims protection from more serious and fatal maladies. This belief advised Franklin’s attitude toward the treatment of the disease, shunning “quacking” and questioning the wisdom of attempting a cure.

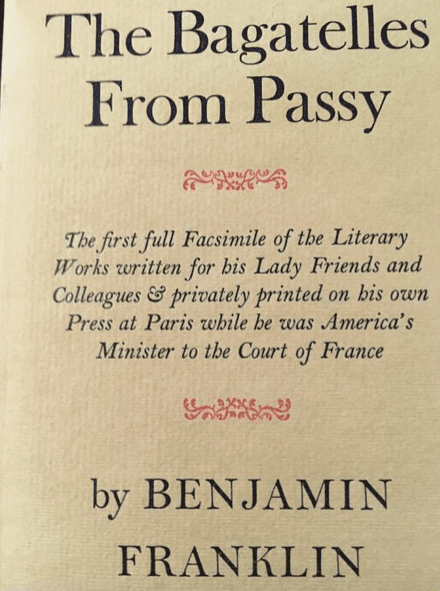

The “Dialogue Between The Gout and Mr. Franklin” was collected as The Bagatelles From Passy by Benjamin Franklin and “Written by him in French and English and printed on his own Press at Paris while he was America’s first Minister Plenipotentiary to the Court of France.” Franklin used his private press for both official documents and for his own pursuits. These playful interludes were not printed in many copies and are extremely rare. The Mason Copy at the Yale University Library is the most complete in existence. Madame Brillon’s “Le Sage Et La Goutte” included in this collection is the only selection not written by Franklin himself.4

Thomas Sydenham in the previous century was the source of the theory that one disease might prevent the occurrence of another deadlier disease. Franklin found that his personal physicians shared this belief or were unwilling to dismiss it. As noted in his dialogue, The Gout maintained that she was his true friend, citing this theory of protection. Franklin was unwilling to treat his condition aggressively although on several occasions he submitted to bloodletting and purging.

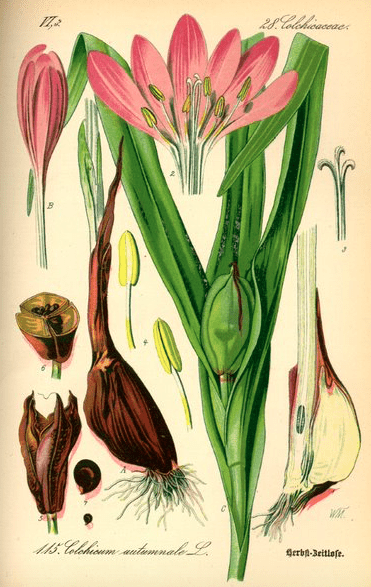

There has arisen an “interesting legend” that Franklin was the first to introduce the use of colchicine for the treatment of gout to America. Franklin was said to have observed the use of wine of colchicum in the treatment of gout, had tried it on himself with beneficial effects, and sent some back to the colonies.5 Colchicine was the only effective therapy available during Franklin’s lifetime, but it is doubtful that he ever used it.6 Knowledge of the drug dates back to antiquity. Alexander of Tralles (sixth century A.D.) recommended its use as gout specific referring to it as hermodactyl, a root used as a cathartic in the treatment of gout. It was derived from Colchicum autumnale, also known as the autumn crocus or meadow saffron. The plant was found in abundance in Colchis on the Black sea. Its toxicity was well recognized. Hildegard of Bingen (1098–1179) forbade its use as a deadly poison as did William Turner (1509–1568), the leading Tudor botanist. While colchicum was listed in the first edition of Pharmacopeia Londineris (1618), it disappeared from editions after 1650 and did not reappear until 1788. Modern usage resumed when Anton Stoerck of Vienna, physician to Marie Theresa, used it as a diuretic for dropsy, anasarca, and ascites but not for gout.7

A French army officer, Nicholas Husson, reintroduced colchicum for gout in a secret concoction he called Eau Médicinale, which he promoted as a cure for gout and a host of other maladies, a polychrest. This aroused opposition to the preparation and its sale in Paris was banned in 1778; remarkably the ban was lifted after five days, presumably because of the beneficial effects in gout. Recognition of its effectiveness continued into the early decades of the nineteenth century when in 1814 Mr. John Want, Surgeon to the Northern Dispensary of London, identified colchicum as the active ingredient in Eau Médicinale and demonstrated the effectiveness of infusions of colchicum corn in acute gout.8 While Franklin might have been aware of d’Husson’s medication, which was in use during the years he was living in Paris, the record is silent as to his ever using the remedy.

Benjamin Franklin’s medical history reveals a number of clearly recognized risk factors for gout and associated bladder stones.9 Included in this list are his age, diet, and alcohol consumption, all clearly satirized in Madame Brillion’s poem and Franklin’s dialogue. To this list can be added gender, family history (genetics), lead toxicity, and psoriasis (which Franklin referred to as “scruf”). Psoriasis is now known to be associated with elevated levels of uric acid and is a risk factor for gout.10

As Franklin ruefully noted, as a young man he did not suffer from gout. It first appeared in middle age and his attacks became more painful and of even longer duration as he grew older. What he did not know when he playfully placed the blame on his amorous deprivations is that kidney function predictably decreases with age, resulting in an elevation of blood uric acid levels and an increased predisposition to attacks of gout. Kidney function, as measured by glomerular filtration, is known to decrease steadily after the age of forty-five and more rapidly after the age of sixty-five.11

That gout spared the “fairer sex” was well recognized in Franklin’s day. Relatives of patients suffering from gout are known to have elevated uric acid levels. Stanley Finger notes that “Franklin’s papers do not suggest a family history of gout, but they show that at least one of his relatives suffered from kidney stones.”

The possibility that his illegitimate son, William Franklin, suffered from gout is suggested in a letter Franklin wrote to Alexander Small in 1780. Responding to an inquiry by Small about his own case of gout,12 Franklin describes putting his “naked” foot out from under the covers during an attack, falling asleep, and achieving relief from his pain. He credits his son, William Franklin, who first gave him an intimation of this practice and “found ease by it.” That he “found ease by it,” seems to suggest that perhaps his son also had personal experience with gout.

As a younger man, Franklin followed the advice on eating moderately that he had given through his alter ego, Poor Richard, in the yearly Almanack he published from 1733–1758. While learning the printing trade in Philadelphia he experimented with a vegetarian diet and consumed a simple diet so as to save funds for the purchase of books. Living for extended periods in Europe, twice in London (1757–1762 and 1765–1775) and then in France (1778–1785), he was by custom and in his diplomatic capacities forced to adopt the dietary practices of his hosts. The prodigious quantities of cold meats regularly consumed by the English gentry during the eighteenth century has been well documented. This was also true in France but perhaps to a lesser extent. Both Madame Brillon and “The Gout” of his famous dialogue reproach him for eating too much for a man who gets no exercise:

. . . Yet you eat an inordinate breakfast, four dishes of tea with cream,

and one or two buttered toasts, with slices of hung beef which I fancy

are not things the most easily digested.

From the writings of Sydenham and others, Franklin knew that his meaty diet made him a target for gout.

Franklin was well aware that wine (alcohol) predisposed to gout. In the 1734 edition of Poor Richard’s Almanack he councils:

Be temperate in wine, in eating, girls and sloth;

Or Gout will seize and plague you both.

The Duc de Croÿ notes in his account of a visit with Franklin in 1779 that “he washed down his foods with two or three bumpers of wine.” He was known to be particularly fond of Madeira and would often consume a second bottle in conversation with a friend. His wine cellar in France contained 216 bottles of Madeira and only 153 bottles of table wine. Today, byproducts of the metabolism of alcohol are known to inhibit the excretion of uric acid by the kidneys and raise the blood level of uric acid. Madeira is one of the fortified wines that contain fifty percent more alcohol than ordinary table wines. These wines also posed a second risk, which was the exposure to lead. Lead is toxic to the kidneys, impairing the excretion of uric acid and causing gout. Franklin was well informed about the effects of lead poisoning and had written on this subject as a young man in Philadelphia. Poor Richard’s Almanack of September 1734 counsels:

Drink Water, Put the money in your Pocket,

And leave the Dry-bellyach in the Punchbowl.

The contamination of lead in rum and resulting lead poisoning (dry-grippes or dry-bellyach) resulted from the use of lead in the distilling equipment and was well recognized in the colonies.

He had collaborated with Dr. George Baker on an important treatise about an epidemic of lead poisoning in Devonshire, England. Sir George Baker (1722-1809) made numerous contributions through papers presented to the Royal College of Physicians from 1767 and 1785 and cautioned against “thickened wines” from Southern Europe. He attributed the source of lead to the distilling equipment, lead-glazed storage vessels, and in some instances the addition of lead sulfates as a sweetening agent. A small sample of fortified wines imported into England during the late eighteenth century and early nineteenth century revealed lead levels of 1.9 mg per liter in Old Canary Wine (1770-1810), 0.83 mg per liter in port from 1805, and 0.16 mg in a bottle of “new port.”13

The second of the “three contraries” that Franklin noted in his letter to George Whately was “the stone”: a bladder stone. In late August 1782 while conducting delicate negotiations for peace between Britain and the United States culminating in the treaty of Paris of 1783, he became seriously ill with symptoms related to a stone. Writing to David Harley, Esqr., Golden Square, London from Passy on September 17, 1782 on the subject of treaty negotiations, he offers an explanation for his delay in answering prior communications: “I have been a long time afflicted with the Gravel & Gout, which have much indispos’d me for writing: I am even now in Pain.” For many weeks during this time, he was ill and unable to attend in-person meetings with the negotiators. From this time forward, Franklin would suffer increasingly severe symptoms from the enlarging stone in his bladder. His symptoms included pain on riding in a carriage followed by bloody urine, stoppage of his “water” in full stream, and eventually pain on changing position in bed because of further enlargement of the stone. When the time finally came for him to depart France and return to Philadelphia in the summer of 1785, he could not endure a carriage ride to the port of Le Havre and the level of the Seine was too low to allow him to travel by barge. To ease his travel, Queen Marie-Antoinette sent her personal litter to be carried by “surefooted Spanish Mules.”14

Franklin was well aware of the problem of stones and as noted above, he had written his parents in 1744 with information for his “Br. John,” the first son of his father’s second marriage to Adiah Folger. He provided medical advice and recommended the use of lime water. His brother’s problem led him to immediately design and have manufactured by a silversmith a flexible catheter, which he forwarded with detailed instructions.15

The association of stones and gout was noted in antiquity. Franklin was aware that Thomas Sydenham had first experienced gout and a decade later was incapacitated by renal calculi. In the eighteenth century the Scottish physician George Cheyne (1671-1743), who himself suffered from gout, established that the chalk taken from the joints of gouty patients was identical to the gravel recovered from their bladders. In An Essay of the True Nature of Treating the Gout in 1724, he noted: “They both have the same colour, taste and smell, . . . and same outward shape.”16

What treatment was available to Franklin for bladder stones and how was his condition treated? In Poor Richard’s Almanack of 1736, he offered this advice to his readers if they were sick: “But if you can get Dr. Inclination, Dr. Experience and Dr. Reason to hold a Consultation together, they will give you the best Advice that can be given.”17 While still in Paris, Franklin prepared a detailed report of his condition and in July 1785 sent it to his friend and physician, Benjamin Vaughn (1751-1835) in London. Vaughn submitted this document to five of the most eminent physicians and surgeons in London. They included the great anatomist and physiologist John Hunter (1728-1793) who signed a letter of advice along with William Heberden (1710-1801), William Watson (1715-1795), and Adair Crawford (1748-1795). Vaughn gathered these documents together and returned them to Franklin with his endorsement. George Corner and Willard Goodwin have documented and discussed these reports in detail, including Franklin’s own case report.18 Their paper provides a fascinating look into medical practice in the eighteenth century.

These consultants, along with the patient himself, were all in agreement that surgery was not to be considered. The Hippocratic Oath affirms: “I will not use the knife, not even, verily, on sufferers from stone, but I will give place to such as are craftsmen therein.” While surgical removal of a bladder stone or lithotomy had been performed in antiquity and the procedure saw improvements during the seventeenth century, it carried a frightful mortality even in younger patients. The prospect of a perineal incision without anesthesia, sterile technique, or the benefit of antibiotics in a man in his middle-to-late seventies was not to be contemplated.

Of the medical therapies available to Franklin at the time, one was lime water (calcium carbonate). In 1752, Franklin mentioned to his older brother John that he had been reading Robert Whytt’s article “On the Virtues of Lime Water in the Cure of Stone” (1752). On January 6, 1784, Franklin in a letter to John Jay confirmed that he had a stone, but that it caused him no pain except when walking or in a carriage. He continued, stating: “You may judge that my Disease is not very grievous, since I am more afraid of the Medicines than the Malady.” What medicines did Franklin take to dissolve the stone and reduce his symptoms? In a letter to Dr. Jan Inenhousz, he mentioned taking Blackrie’s solvent, which he hoped “will have some effect in diminishing the Symptoms, and Preventing the Growth of the Stone.” In a letter to Benjamin Vaughn, he mentioned the receipt of “a bottle of Blackie.” He had also requested from a nephew in London a copy of Blackrie’s Disquisition upon Medicines that Dissolve the Stone. Blackrie’s Solution, or Lixivium, was initially the secret remedy for urinary calculi of a physician in Bath by the name of Chittick. Alexander Blackrie, a Scottish apothecary, identified it to be “a solution of alkaline fixed salts combined with quicklime, or soap lye.” Another approach that Franklin had tried for some time was a prescription of honey, molasses, and jellies. This practice was aimed at increasing the buoyancy of the urine and preventing the further aggregation of stone-forming elements. This mistaken notion reflected a school of iatro-chemical thinking that evolved during the seventeenth century.

Franklin left France on July 12, 1785 while the London doctors were still considering his case. The stone continued to enlarge and torment him. Despite his advancing age and increasing discomfort, following his return to Philadelphia he remained amazingly active and involved politically. He was elected President of the Council of Pennsylvania, took an active part in the Constitutional Convention of 1787, supervised the erection of five houses, and corresponded with friends in Europe and America. He authored a number of philanthropic and political papers.

By the summer of 1789, his resistance to pain had reached a limit and he resorted to taking opium. William Heberden had recommended the use of opium for people with large inoperable stones. In September 1789, he wrote to his friend and neighbor at Passy, Louis-Guillaume Le Villard (1733-1794), that having been afflicted with constant and grievous pain he had resorted to opium, which afforded him relief but took away his appetite, leaving him emaciated. He did have some periods when he was free of pain. On March 24, 1790, less than a month before he died, he was able to write his sister, Jane Mecom, that he had been free of pain for three weeks and not “obliged to take laudanum.”

His torment from the stone ended on April 17, 1790. George W. Corner and Willard E. Goodwin posit that the stone may have enlarged to occupy most of the bladder and weighed possibly 400 to 500 grams. His kidneys may have been damaged and uremia (renal failure) may have contributed to his death.19

Franklin to the end was philosophical about his “contraries.” Perhaps he expressed this best in words he penned to Louis-Guillaume Le Villard in the spring of 1787:

People who live long, who will drink of the cup of life to the very bottom, must expect to meet with the usual dregs and when I reflect on the number of terrible maladies human nature is subject to, I think myself favoured in having to my share only the stone and the gout.20

References

- Benjamin Franklin, Autobiography, Poor Richard, and Later Writings, The Library of America, 1997, On Annihilation and Bifocals, To George Whatley, pp. 364 – 370

- Benjamin Franklin’s Autobiography: Authoritative Texts, Background, Criticism, edited by J.A. Leo Lemay and P.M. Zall, Norton Critical Edition, 1986, p. 67

- The Bagatelles from Passy, Benjamin Franklin, Text and Facsimile, The Eakins Press, New York Publishers, 1967. p. 81. The informative notes and background to this elegant publication were prepared by Claude-Anne Lopez, the Assistant Editor, The Franklin Papers, Yale University.

- F. B. Adams, Jr., Franklin and His Press at Passy, The Yale University Library Gazette, 30 (4) 133-138, April 1956. For those interested in details about how Franklin established and used the private press he established at Passy, this article provides a delightful summary.

- Maurice A. Schnitker, A History of the treatment of Gout, Bull. Hist. Med., 1936, 4:89-120,

- Stanley Wallace, Benjamin Franklin and the Introduction of Colchicum into the United States, Bulletin of the History of Medicine, 42 (4): 312-320, July 1968

- Roy Porter and G.S. Rousseau, Gout: The Patrician Malady, Yale University Press, 1998, pp. 17-18, 131-132.

- Gerald P. Rodnan and Thomas G. Benedek, The Early History of Antirheumatic Drugs, Arthritis and Rheumatism, 13: (2), March-April 1970. The authors provide a comprehensive history of Eau Médicinale. They also tried to learn more about Mr. John Wan and only can identify that he was a member of the Royal College of Surgeons in 1809.

- Stanley Finger and Ian S. Hagemann, Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, 152: No. 2, 189-206, June 2008

- Stanley Finger, Doctor Franklin’s Medicine, University of Pennsylvania Press. Chapter 16 Skin and “Scruff” is devoted to this subject.

- John W. Rowe et. Al., The Effect of Age on Creatinine Clearance in Men: A Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal Study, Journal of Gerontology, 31 (2): 155-163, 1976

- Treatment of Gout, to Alexander Small, Passy, July 22, 1780. The Ingenious Dr. Franklin, edited by Nathan G. Goodman, University of Pennsylvania Press, 1931, p. 23

- Erik Skovenborg, Lead in Wine Through the Ages, Journal of Wine Research,6:49-64,1995.

- Walter Isaacson, Benjamin Franklin: An American Life, Simon and Schuster, 2003, p. 433

- Houston M. Kimbrough, Jr, Investigative Urology, 12 (6): 509-508, 1975.

- Ibid, Stanley Finger, p. 301

- Ibid, Benjamin Franklin, Poor Richard: The Alamacks, p. 41 (November)

- George W. Corner and Willard E. Goodwin, Benjamin Franklin’s Bladder Stone, Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences, 359 – 377, 1953

- Ibid Corner and Goodwin, p. 376

- To Louis-Guillaume Le Veillard (unpublished), Philadelphia April 15, 1787

JAMES L. FRANKLIN is a gastroenterologist and associate professor emeritus at Rush University Medical Center. He also serves on the editorial board of Hektoen International and as the president of Hektoen’s Society of Medical History & Humanities.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 13, Issue 3 – Summer 2021