JMS Pearce

Hull, England

“. . . A man among the little band of whom are Aristotle and Newton and Darwin.”

-Gustave I. Schorstein (1863-1906), physician at the London Hospital

The magnitude of Hughlings Jackson’s contributions to medicine is almost impossible to encapsulate. He was the foremost figure of nineteenth-century British neurology. He has enjoyed numerous encomia, which he would have modestly refuted, and like Thomas Willis before him, and Jean-Martin Charcot, he has been named the Father of Neurology. These giants in very different ways dominated their world of clinical neurology and research.

John Hughlings Jackson (1835-1911) (Fig 1) was born in a house named Providence Green (Fig 2) in the pretty village of Green Hammerton near York, the son of Samuel Jackson, a brewer and yeoman, and Sarah Jackson (née Hughlings). The name Hughlings came from his mother. He first attended the village school in Green Hammerton, but details of his later schooling are unclear.

Aged just fifteen he was apprenticed in October 1850 to Dr. William Charles Anderson at 23 Stonegate, who lectured at York Medical School. He saw patients at the County Hospital in Monkgate, in the Public Dispensary, and in the humane Quaker asylum, The Retreat.

Medical training was just beginning to be regulated to separate doctors from unqualified quacks. The York Medical School was founded in 1834 and ceased in 1862. There he acquired knowledge and inspiration at the hands of Thomas Laycock (1812-1876), an accomplished physician who became Professor of Medicine at Edinburgh, and Dr. Daniel Hack Tuke (1827-1895), great-grandson of William Tuke, founder of The Retreat. He completed his training at St. Bartholomew’s Hospital in London. The Worshipful Society of Apothecaries accepted his training in York as a qualification for their license and on 10 April 1856, he passed their examination at the Apothecaries Hall. He promptly returned to the York Dispensary.

In 1859 he returned to London. He carried a letter of introduction and commendation from Dr. Proctor, his anatomy teacher, to the later famous Jonathan Hutchinson who had been seven years his senior at the York Medical School and who was established as a young surgeon at the London Hospital. He stayed with Hutchinson, a lifelong friend, at 4 Finsbury Circus. Hutchinson helped him to find work at the Metropolitan Free Hospital and at the London Hospital, where he met the influential and kindly Sir James Paget. Jackson furthered his career in 1860 by obtaining the MD at St. Andrew’s, and in 1861 the MRCP London. In 1862 he was appointed assistant physician to the National Hospital for the Paralysed and Epileptic, which had opened just two years earlier. He was elected FRS in 1878. His wide excursions in neurology were founded at the London and at the National Hospitals. With Hutchinson he was a reporter for the weekly Medical Times and Gazette. He eventually moved to live at 3 Manchester Square.

Cerebral localization

Some of his most important work was in localizing functions and diseases in the brain, based on his minute bedside observations, particularly of epilepsy. Fritsch and Hitzig in 1870, using Galvanic stimulation of the brain, had shown the localization of motor function in the hemispheres of the dog.1 Jackson’s clinical deductions stimulated David Ferrier,2 who carried out experiments at the West Riding Pauper Lunatic Asylum at Wakefield to establish the principles of cerebral localization. The Wakefield asylum was unique in its day for the combination of caring for the mentally ill and simultaneously carrying out scientific laboratory experiments and pathology. From it was issued The West Riding reports 1871-6, which had several eminent contributors. With Jackson’s guidance it became the journal Brain in 1878, still the most prestigious neurology journal in the world.

Amongst Jackson’s papers in the West Riding Lunatic Asylum Reports (1873–1876) were:

On the localization of movements in the cerebral hemisphere

On the anatomical, physiological’ and path’ investigation of epilepsies

Recovery from optic neuritis without defects of sight

On recovery from double optic neuritis

On epilepsies and after-effects of epileptic discharges

Temporary mental disorders after epileptic paroxysms

Such was his influence that Ferrier dedicated to him his book The Functions of the Brain, 1876:

“To Dr. Hughlings Jackson, who from a clinical and pathological standpoint anticipated many of the more important results of recent experimental investigation into the functions of the cerebral hemispheres. This work is dedicated as a mark of the author’s esteem and admiration.”

Epilepsy

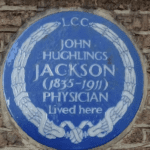

Fig 3. Blue plaque at 3 Manchester Square, London. Photo by Spudgun67. Via Wikimedia.

Jackson began by emphasizing the focal lesion as the key to analyzing the origins of patients’ symptoms. His unrivaled appraisal of epilepsy in its diverse manifestations was a primary source. He defined epilepsy: “A convulsion is but a symptom, and implies only that there is an occasional, an excessive, and a disorderly discharge of nerve tissue on muscles,”3 a “sudden disorderly expenditure of force.”4

Epilepsy was a symptom, not a disease. The epileptic discharge was a “physiological fulminate like the gunpowder in a cannon. Just as gunpowder can store energy that is liberated when the gun is fired, so the energy stored in nerve cells can be explosively liberated in an epileptic discharge.”5 He used the patterns of focal epilepsy to show:

When the fit begins in the hand, the index-finger and thumb are usually the digits first seized; when in the face, the side of the cheek is first in spasm; when in the foot, almost invariably the great toe . . . In each of these varieties there must be some difference in the situation of the grey matter exploded.3(p. 68)

He described the spread or march of convulsive movements in a fit, called by Charcot5 “Jacksonian epilepsy.” Movements, rather than individual muscles, were represented in the cortex.6 His supposition was that although each movement is everywhere represented, there were points where particular movements were specially represented.7 The “Jacksonian March” developed from the successive recruitment of elements of different weighting.

Following Robert Bentley Todd, he regarded focal epilepsy and paralysis as reciprocal events; the nervous system was an exclusively sensorimotor machine, a purely physical mechanism, distinct from popular metaphysical conjectures. It was composed of a number of physiologically (not anatomically) discrete organs, each with a single function accessible to the physician. He distinguished the facts of localization from the concepts of function.

A convulsion was a positive phenomenon as opposed to the negative phenomena of paralysis. By observing the march of epileptic seizures he developed the crucial idea of somatotopic representation in the brain. Thus the analysis of the temporal development (march) of a focal neurological deficit proved an invaluable diagnostic principle. His lucid descriptions included the diverse intellectual, psychic, dreamy states, sensory, motor, and aphasic contents of various types of seizures, as well as the several post-epileptic states.8,9

Evolutionary hierarchy

The psychologist/philosopher Herbert Spencer (1820–1903) had provided the notion of dissolution and evolution of the nervous system.10,11 Based on his admiration for Spencer, Jackson developed his own notion that the nervous system represents an evolutionary hierarchy. It had three levels—a progression from simple to complex involving structure and functions, connected by the process of weighted ordinal representation.12 The lowest level consists of the anterior spinal horns and homologous cranial motor nerve nuclei. The middle level is composed of the motor cortex and the basal ganglia. The highest level consists of the premotor frontal cortex.

We shall be very much helped in our investigations of diseases of the nervous system by considering them as reversals of evolution, that is, dissolution. Dissolution is a term I take from Spencer as a name for the reverse of the process of evolution.13

Jackson extended Russell Reynolds’ idea14 of positive and negative symptomatology. Negative symptoms (paralysis, sensory impairments, dysphasia) related to dissolution of neural function,15 while positive symptoms (clonus and convulsions) resulted from excitation or release of lower levels from higher inhibitory control:11, 15,16

. . . There are degrees of loss of function of the least organized nervous arrangements with conservation of function of the more organized. There is in each reduction to a more automatic condition; in each there is dissolution, using this term as Spencer does, as the opposite of evolution.17

For Jackson, consciousness and mental states were the highest level of mental evolution. He applied this principle to aphasia, hemiplegia, and clonic movements; it also was applied later to psychiatry.18 From this, he developed his brain–mind theory, a form of “psychophysical parallelism,” which he called the Doctrine of Concomitance, which separated the psychiatric from physical disorders of the brain:

The doctrine I hold is: first that states of consciousness (or, synonymously, states of mind) are utterly different from nervous states; second, that the two things occur together—that for every mental state there is a correlative nervous state; third, that, although the two things occur in parallelism, there is no interference of one with the other. This may be called the doctrine of Concomitance.19

“All nervous centers are made up of nothing else than nervous arrangements representing impressions and movements . . .”20 Every mental state at the highest level of evolution correlated with a nervous [i.e. neural] state, but consciousness was the only mental function, which limited concomitance to consciousness—the highest level of neural evolution. He rejected the unconscious because empirically it was not observable at the bedside; any state of mind is by definition conscious.

From his minute clinical observations, he would spend much time in “armchair contemplation” of their significance in relation to normal and abnormal functioning of the brain. Like great thinkers in all disciplines, it was his passion and imagination that determined the originality of his ideas. He would critically test and re-test them by further observations, or he would seek confirmation or rejection in pathological anatomy and in the operating theater. He often refuted conclusions that were not demonstrable clinically. He would change his opinions, showing his intellectual honesty and his strict empiricism. Sir Francis Walshe observed that he used neither apparatus nor animal experiment, but that his contributions came through the application of a scientific imagination to the material of his observations.

Although his writing is often recondite, its contained ideas remain profound syllogisms that have proved valid, and of immense importance to the practicing neurologist. They are difficult to read because they teem with hitherto unknown ideas, jostling one another. Henry Head noted that anxious not to overstate his case, almost every page is peppered with explanatory phrases or footnotes.

Eccentric but courteous in his habits,23 he was a modest, gentle, shy man who sedulously avoided publicity. Sir Edward Farquhar Buzzard described him as a generous, kind-hearted, but rather grave family friend or pseudo-uncle whose mind seemed to be in a state of constant conflict between his desire to give pleasure and his fear of being bored or bound.

In 1865 he married his cousin Elizabeth Dade Jackson, but in May 1876 she died childless of cerebral thrombophlebitis with frequent focal seizures. He was inconsolable but died of pneumonia on 7 October 1911 and was buried at Highgate Cemetery in London.

Of many biographies and accounts of Hughlings Jackson’s works,7,13,21 the book by Macdonald and Elaine Critchley is unrivaled as the prime source of reference.22 James Taylor collected his many papers with commentaries.3

References

- Fritsch G, Hitzig E. Über die elektrische Erregbarkeit des Grosshirn [On the Electrical Excitability of the Cerebrum], Archive für Anatomie, Physiologie und wissenschaftliche Medicin, 1870(pg. 300-32)

- Pearce JMS. Sir David Ferrier MD, FRS. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2003 Jun;74(6):787.

- Taylor J (ed). Selected writings of John Hughlings Jackson. Staples Press, London 1931.

- Jackson JH. Note on the comparison and contrast of regional palsy and spasm, Lancet, 1867, vol. i (pg. 295-7).

- Charcot JM. , Leçons du mardi à la Salpêtrière [Lectures at the Salpêtrière], Paris, Delahaye & Lecrosnier, 1887

- Phillips CG. Cortical Localization and ‘Sensorimotor Processes’ at the ‘Middle Level’ in Primates. J Roy Soc Med 1973;66:987-1002.

- Jackson JH. Remarks on the disorderly movements of chorea and convulsion, Med Times Gazette, 1867, vol. ii (pg. 669-70)

- Jackson JH (1881) On temporary paralysis after epileptiform and epileptic seizures: a contribution to the study of dissolution of the nervous system. Brain 3:433–451.

- Jackson JH (1870) A study of convulsions. Transactions of St. Andrews Medical Graduates Association, 1870; 3: 162–204.

- Spencer H. Principles of psychology. London: Longman, Brown, Green, 1855.

- Spencer H. First principles. London: Williams & Norgate, 1911.

- Swash M. Kennard C, Swash M. John Hughlings Jackson. A historical introduction, Hierarchies in neurology: a reappraisal of a Jacksonian Concept, London Springer Verlag, 1989

- Jackson JH. Evolution and dissolution of the nervous system. Croonian Lectures delivered at the Royal College of Physicians, March 1884. Lancet 1884;1:555-8,649-52,739-44.

- Russell Reynolds J. Epilepsy: its symptoms, treatment and relation to other chronic convulsive disorders. London: John Churchill; 1861

- Jackson JH. The Croonian Lectures On Evolution And Dissolution Of The Nervous System. Delivered at the Royal College of Physicians. Lecture I. British Medical Journal. 1884;591-3.

- Pearce JMS. Positive and negative cerebral symptoms: the roles of Russell Reynolds and Hughlings Jackson. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2004; 75: 1148.

- Jackson JH. Remarks on dissolution of the nervous system as exemplified by certain post-epileptic conditions. Medical Press and Circular 1881;329.

- Andreasen NC, Olsen S. Negative v positive schizophrenia. Definition and validation. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1982;39:789–94.[Abstract]

- Jackson JH. The Croonian Lectures on Evolution and dissolution of the nervous system. Lecture III British Medical Journal 1884;1:703-707.

- York GK, Steinberg DA. Hughlings Jackson’s neurological ideas. Brain 2011, 134 (Pt. 10): 3106-13.

- [Anon] An Introduction to the Life and Work of John Hughlings Jackson: Introduction. Med Hist Suppl. 2007;(26):3-34.

- Critchley M, Critchley EA. John Hughlings Jackson: Father of English Neurology. Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1998.

JMS PEARCE, MD, FRCP, is emeritus consultant neurologist in the Department of Neurology at the Hull Royal Infirmary, England.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 13, Issue 3– Summer 2021

Leave a Reply