Nicolas Roberto Robles

Badajoz, Spain

|

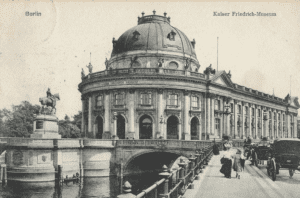

| Figure 1. Kaiser Friedrich Museum (currently Bode Museum) on the Monbijou Bridge in Berlin, 1905. Public domain. Via Wikimedia |

Un médico cura; dos, dudan; tres, muerte segura.

One doctor, health; two, doubt; three, certain death.

-Spanish saying.

Friedrich III of Hohenzollern was the second Kaiser of Germany and eighth King of Prussia. After completing his studies, which combined military training and liberal arts, he married Princess Victoria, daughter of Queen Victoria, in 1858. Because of his liberal ideas, the prince gradually moved away from his father, King Wilhelm I, and especially from the head of government, Chancellor Otto von Bismarck. Although he was the heir to the throne, the prince was removed from political affairs and relegated to a merely representative role. After twenty-seven years as Kronprinz (heir to the throne), Friedrich finally succeeded his father as King of Prussia and German Emperor on March 9, 1888. However, he suffered from advanced laryngeal cancer and died soon after taking the throne, unable to carry out his planned reforms.

Friedrich received contradictory medical advice about his cancer. In Germany, Dr. Ernst von Bergmann suggested that his larynx should be completely removed, while his colleague, Dr. Rudolf Virchow, opposed the idea because this kind of operation had not been completed without causing death to the patient. At the request of Friedrich’s wife, the famous British laryngologist Sir Morell Mackenzie, the most eminent throat specialist of the Victorian era, was consulted. He did not diagnose cancer, but advised a simple cure in Italy, a plan that was accepted by both the emperor and his wife. The diagnosis was one that had not only personal but also political importance since it was unsure whether anyone suffering from an incapacitating disease like cancer could, according to the family law of the Hohenzollerns, occupy the German throne. There had been talk of renunciation by Friedrich when he was still crown prince.

|

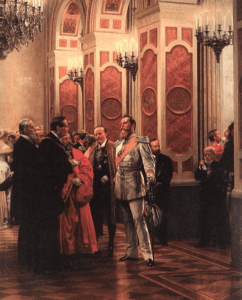

| Figure 2. Kaiser Friedrich III when he was the Crown Prince, in conversation with dignitaries at a court ball. Adolph von Menzel (1885). Public domain. Via Wikimedia |

On February 8, 1888, a month before the death of Wilhelm I, Dr. Bergmann surgically inserted a cannula in Friedrich to allow him to breathe, an operation that deprived him of speech. Dr. Bergmann almost killed the heir to the throne by making the incision in the windpipe and directing the cannula to the right side of the throat. Friedrich began to cough and bleed and Bergmann inserted his index finger—without any kind of protection—into the wound to position the cannula properly. The bleeding subsided after two hours, but the doctor’s action produced an abscess in Friedrich’s neck. Pus quickly accumulated, causing great discomfort in the last months of the emperor’s life. After the operation, the prince complained to his relatives about the bad treatment and wondered “why Bergmann put his finger down my throat.” A few weeks later, Dr. Thomas W. Evans performed a successful tracheostomy with a silver cannula. Friedrich III was only emperor for ninety-nine days. He died on June 15 and his eldest son, the young Wilhelm II, succeeded him on the throne. Friedrich was buried in a mausoleum attached to the Friedenskirche in Potsdam.

The discrepancies between the initial diagnoses and the final outcome of the Kaiser’s disease created a never-ending medical controversy. Three biopsies of his laryngeal lesion were taken by Mackenzie in 1887 and diagnosed by Virchow as “pachydermia verrucosa larynges,” confirming Mackenzie’s assessment that the Kaiser’s disease was benign. A fourth specimen coughed up by the patient was considered by Virchow to be nondiagnostic. Another specimen expectorated by the patient three months before his death was diagnosed as carcinoma by Wilhelm Waldeyer. The autopsy revealed squamous carcinoma in the larynx with a cervical lymph node metastasis. It has been suggested that the neoplasm that challenged the diagnostic skills of the founder of pathology was hybrid verrucous carcinoma (HVC), an extremely rare, metastasizing variant of verrucous carcinoma (VC) composed of pure VC mixed with clusters of conventional squamous cell carcinoma.1

In addition to the political considerations, since laryngeal neoplasms operations had an extremely high mortality at that time, histopathologic examinations were made in order to decide for or against an operation. The first samples did not meet Virchow’s criteria for a carcinoma. Contrary to the present understanding of carcinoma progression, Virchow’s concept was based on the assumption that carcinomas were not derived from the epithelium but arise from a mesenchymal-epithelial transformation of connective tissue.2 Virchow strongly believed that the tumor, like any other physiological or pathological phenomenon, was always a part of the patient’s body, being strictly subject to the laws of biology. He consistently applied the concepts of cell physiology to all pathological processes, even cancer. This idea had been helpful in defining biological processes during the 1850s, but was losing much of its advantage with regard to the histopathological diagnosis of cancer towards the end of the nineteenth century. Virchow was convinced that he could only preserve his uniform cellular theory by doing without a specific characterization of the tumor cell.3

|

| Figure 3. Marble grave of Kaiser Friedrich III and his wife, the Kaiserin Victoria. Friedenkirche. Postdam. Via Wikimedia |

Bernhard Minnigerode had a different point of view.4 The German laryngologist M. Schmidt in November 1887 had expressed the view, based on his own examination of the patient, that the existing neoplasia had developed from underlying syphilis. Moreover, in the joint medical examination of the crown prince by Schrötter, Mackenzie, and Krause on November 9, 1887, the latter expressed the same view. Even more, Mackenzie said to a mutual friend that Friedrich had doubtless had syphilis before the cancer. The genesis of a carcinoma on the basis of a syphilitic gumma has often been observed, though the direct transition of the syphilitic lesion into carcinoma is not frequent. In 1869 Frederick had participated in the festivities on the occasion of the opening of the Suez Canal as representative of King Wilhelm I. The viceroy of Egypt gave the guests the experience of “oriental nights,” including sumptuous festivities and women whom he gave away to his visitors on all sides. It is supposed that the Kronprinz could be infected on this occasion. A lapse of ten to twenty years (and even longer) is usually observed for the occurrence of tertiary syphilis laryngeal manifestations after the primary infection. Still, this possibility cannot be absolutely excluded.

Scilicet hac tenui rerum sub imagine multum

Naturae, fatique subest, et grandis origo.

Fracastoro (Syphilis, I. 22-4)

“Be certain that beneath the slender appearance of this topic there lies concealed a vast work of nature and of fate and a grand origin.”

End Notes

- Cardesa A, Zidar N, Alos L, Nadal A, Gale N, Klöppel G. The Kaiser’s cancer revisited: was Virchow totally wrong? Virchows Arch. 2011; 458(6):649-57.

- Hussein K, Panning B. Rekonstruktion der Befundung des Larynxkarzinoms Kaiser Friedrichs III. durch Rudolf Virchow [Pathologe. 2018 Mar;39(2):172-177.

- Bauer AW. “… unmöglich, darin etwas Specifisches zu finden”. Rudolf Virchow und die Tumorpathologie. Medizinhist J. 2004;39(1):3-26.

- Minnigerode B. The disease of Emperor Frederick III. Laryngoscope. 1986;96(2):200-3.

NICOLAS ROBERTO ROBLES is a professor of Nephrology at the University of Extremadura, Spain.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 13, Issue 2– Spring 2021

Fall 2020 | Sections | History Essays

Leave a Reply