JMS Pearce

Hull, England

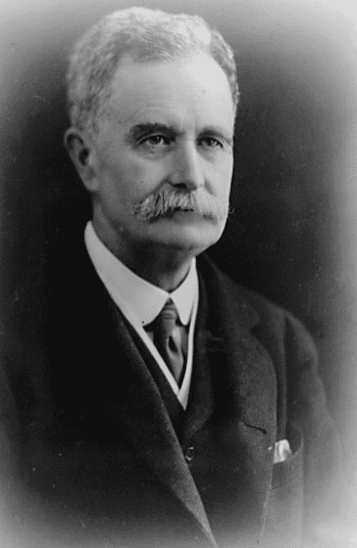

Howard Tooth (1856-1925) was one of many physicians who served well their patients and their profession, but who would be unknown save for a syndrome that bears and perpetuates their name.

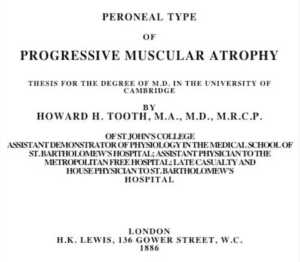

Howard Tooth (Fig 1) was born in Hove, Sussex, educated at Rugby School and at St. John’s College, Cambridge, where he qualified MRCS in 1880 and MRCP in 1881. He had his clinical training at St. Bartholomew’s Hospital, London, where he investigated hereditary peroneal muscular atrophy, culminating in his MD thesis read on 26 May 1886 to the University of Cambridge.1 (Fig 2)

After undergraduate studies in Cambridge (BA, 1877), Tooth trained in medicine at St. Bartholomew’s Hospital (qualifying in 1880) where he was subsequently on the consultant staff (1895–1921). He became physician to the London Metropolitan hospital in 1887. His neurological interest led to his appointments at The Hospital for The Paralysed and Epileptic, Queen Square, as an outpatient physician in 1900 and full physician in 1907, joining an array of eminent contributors to neurology.a He was awarded the esteemed Goulstonian Lecture of the Royal College of Physicians of London in 1889 on Secondary degeneration of the Spinal Cord, and became Censor to the college.2 His substantial paper on The Growth and Survival Period of Intracranial Tumour… was the definitive study at the time.3 Tooth was also a competent microscopist.4 He lived at 34 Harley Street until his retirement.

During the Boer War, with bravery and distinction, he served in South Africa for which he was awarded the Order of St. Michael and St. George (CMG) in 1901. And in the First World War he served in England, Malta, and Italy, reaching the rank of colonel; he was honored as Companion of the Order of the Bath (CB) in 1918. Ill health, from which he never fully recovered, caused him to return before the end of the First World War. However, he remained in active and much valued practice at Bart’s and published several important articles in Brain and elsewhere. Although colleagues believed that his early promise was not wholly fulfilled, patients and students appreciated his sympathy, thoroughness, and clinical skills. A Bart’s colleague, H. Morley Fletcher, remarked:

He had to an unusual degree a bright and sunny temperament which endeared him to all, and this was combined with a most transparent honesty of character to which the faintest touch of chicanery was abhorrent.

Like many Victorian doctors, he was a man of catholic interests: a talented musician, woodworker, and gardener. He was married twice, first to Mary Beatrice Price, then to Helen Katherine Chilver by whom he had a daughter and two sons. Whilst driving his car he suffered a cerebral hemorrhage and died three months later at home in Hadleigh, Suffolk in 1925. Ironically, with Samuel Jones Gee (1839 –1911), who first identified celiac disease, he had described pontine hemorrhage in an 1898 paper in Brain.

Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease (Peroneal Muscular Atrophy)

Tooth’s thesis on hereditary peroneal muscular atrophy was published in 1886 and in a review in 1887.5 In the same year, JM Charcot and Pierre Marie published a similar clinical account of five cases,6 so that the syndrome is justly remembered as Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease. Tooth had noted:

Since this thesis has been commenced, and some months after the lines, on which it was intended to work, had been laid down, there appeared in the Rev. de Médicine for Feb. 1886, a paper by MM. Charcot and Marie on the same subject illustrated by five cases. I take this opportunity at the same time, of acknowledging my indebtedness to M. Charcot for his able Revue Nosographique in the Prog. Médical, March 1885, which first directed my attention to the subject of amyotrophy.

They all acknowledged several earlier descriptions that were later collected by Schultze.7

They described a disorder mainly affecting adolescents and young adults, characterized by slowly progressive wasting and weakness of the lower legs, resulting in pied en griffe with the classic champagne-bottle configuration of the legs and pes cavus. Sensory loss was absent or mild, and progression to the hands was a late feature. Scoliosis and other skeletal deformities were common. Charcot and Marie thought it was a myelitic disease, whereas Tooth correctly suggested a peripheral neuropathy.5,8

Later writers recorded several variants, including the Roussy-Lévy syndrome with tremor and, Dejerine-Sottas syndrome with hypertrophy of peripheral nerves.

More recently, other variants have been identified within this pleomorphic syndrome.9 The descriptions in 1886 were followed by a period of nosological confusion. This was partly clarified by the advent of nerve conduction studies and the classification of hereditary motor and sensory neuropathies (HMSN) types I and II10 and an X-linked form. The classification has changed with the identification of underlying mutations in genes (most commonly a duplication of a region on the short arm of chromosome 17) encoding myelin proteins;11 more than ninety “causative” genes of CMT have been identified.12

End Note

- His contemporaries there included some famous names: H. Charlton Bastian, W. R. Gowers, David Ferrier, J. A. Ormerod, Charles E. Beevor, James Taylor, J. H. Risien Russell, W. Aldren Turner, Frederick E. Batten, and Felix Semon.

Reference

- Tooth HH. The Peroneal type of Progressive Muscular Atrophy. London, HK Lewis 1886.

- Munk’s Roll. Lives of the Fellows of the Royal College of Physicians of London, Vol IV (1826-1925). Compiled by GH Brown. London: Published by the College. 1955. pp. 331

- Tooth HH. Some observations onthe Growth and Survival Period of Intracranial Tumours, based on the records of 500 cases, with special reference to the pathology of gliomata. Brain 1912-13;35:61-72.

- Pearce JMS. Howard Henry Tooth C.B., C.M.G., M.D., FRCP. J Neurol 1999; 196-7.

- Tooth H H. Recent observations on progressive muscular atrophy. Brain (July) 1887; 10 (part XXXVIII): 243–253;

- Charcot JM, Marie P. Sur une forme particulière d’atrophie musculaire progressive souvent familiale débutante par les pieds et les jambs et atteignant plus tard les mains. Rev Med 1886; 6:97

- Schultze F. Über den mit Hypertrophie verbundenen progressiven Muskelschwund und ähnliche Krankheitsformen. Wiesbaden (1886)

- Compston A. From the Archives. Brain 2019;142 (8): 2538–2543,

- Thomas, P.K., Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease – Historical Perspective and Overview, published in Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disorders: A Handbook for Primary Care Physicians, Charcot-Marie-Tooth Association, 1-4, 1995.

- Dyck PJ, Lambert EH. Lower motor and primary sensory neuron diseases with peroneal muscular atrophy. I. Neuron- logic, genetic and electrophysiologic findings in various neuronal degenerations. Arch Neurol 1968; 18:619-25

- Rossor AM, Polke JM, Houlden H, Reilly MM. Clinical implications of genetic advances in Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease. Nat Rev Neurol. 2013 Oct; 9(10): 562-71.

- Harding AE. From the syndrome of Charcot, Marie and Tooth to disorders of peripheral myelin proteins, Brain, 1995; 118, (3): 809–818, https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/118.3.809

JMS PEARCE, MD, FRCP, is an Emeritus Consultant Neurologist Department of Neurology, Hull Royal Infirmary, and an author with a particular interest in the history of science and medicine.

Leave a Reply