|

| William Jones by John Linnell (1792–1882) after the original of Joshua Reynolds. Via Wikimedia. CC BY-SA 4.0. |

Somewhere around 3,000 to 7,000 years ago there lived in the steppes of southern Ukraine, or perhaps in northern Anatolia, a group of people whom we now call Indo-European but about whom we know very little. They left a few burial mounds, some pottery and skeletons, but their history is obscure. They spoke a presumed language known as Proto-Indo-European. From certain roots of words that have come down to us, we believe they tilled the land and drank strong mead, chased wolves and bears, felled beech trees, domesticated cattle, had horses and dogs but not cats, navigated rivers but did not live by the sea, and may have created the first wheeled vehicles. They are the forefathers of almost any language currently spoken in Europe, and beyond. To learn about them in school or college would greatly enhance the perspective of young people seeking an education, and doctors would benefit from a cursory exposure to the discipline of linguistics because most of the words used in their practice come from them.

The modern story of the Indo-Europeans begins in Calcutta, where, in 1786 at the meeting of the Asiatic Society of Bengal, Sir William Jones, High Court judge of India, delivered a paper in which he noted many similarities between ancient Sanskrit and modern European languages. He wrote that Sanskrit was “of a wonderful structure; more perfect than the Greek, more copious than the Latin, and more exquisitely refined than either,” a perfect language, with which many linguists may disagree, and that it was the common ancestor of most European languages, which is generally agreed upon.

|

| Wilhelm and Jacob Grimm, 1847; daguerreotype by Hermann Blow. Via Wikimedia. |

Indo-European was a highly inflected language that had eight cases, six tenses, and the so-called ablaut, meaning a change in the vowel from present to past tense (write-wrote, hang-hung). From their language, or rather from its surviving roots, one may also surmise that they buried their dead (sepulcher—sepelio), worshiped gods and perhaps money (Pluto—plutocrat, Jupiter—deus-pater), and gave us the word credo (cor heart, do to give). They had names for body parts, and agricultural terms for the stars, moon, sun, and snow. The word law is derived from legge or lego, to bind. Likewise, the Indo-European root rix is clearly closely related to the German “Reich,” to being rich, or to the rix in Vercingetorix, meaning the king of the Gauls. Words ending in inth such as Corinth, hyacinth, plinth, and labyrinth are not Indo-European but represent another linguistic group.

At some time the Indo-Europeans split into two large groups, one moving west, the other east. These are designated by the respective designations of “hundred” as centum or satem languages, those moving west having retained an N in words such as in “cent,” and those in the east having dropped the N, such as in Farsi. The centum languages include the large Germanic and Romance languages, as well as Greek, Celtic, Albanian, and the extinct Hittite, Tocharian, old Prussian, Thracian, Dacian, Macedonian, Illyrian, Venetian, and several others. The Eastern branch includes Iranian, Indian, Slavic, Baltic, and Armenian.

Linguistic history indicates that the Western group further split into two large groups, Germanic in the north and Romance or Mediterranean in the South. Their languages diverged from one another, and the major letters of one group were often replaced by others in the other group. These changes have been subject to the studies of many linguists. Predominant among these were the two brothers Grimm, more widely known as authors of fairytales designed to amuse the good children and scare the bad ones into obedience.

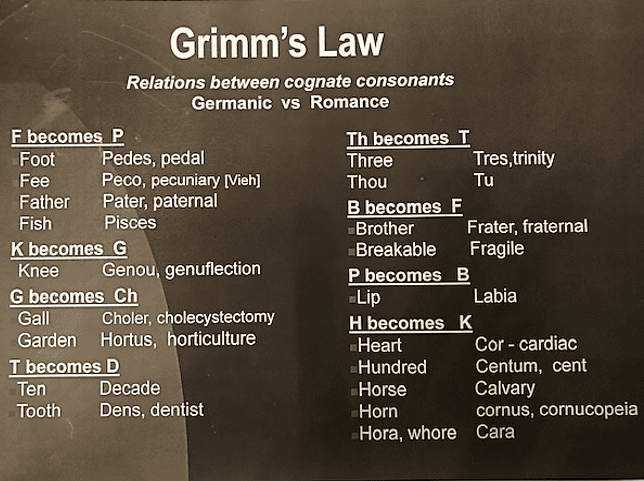

The Grimms’ findings have been promulgated into “laws,” and here is where the fun starts. Podiatrists treat feet because the letter P becomes the cognate Romance F. When you genuflect, you get on your knees, it is the dentist who treats your teeth, fraternal means brotherly, and labial refers to the lips. A cardiac arrest means your heart has stopped because no cardiologist was around, but had you liked riding horses you might have been in the cavalry and perhaps might the been a cavalier. In a strange change of meaning, what we held close became a pejorative, so cara, meaning dear, becomes hora and in ancient English whore. A table is enclosed for guidance and to remind us that language, like civilization in general, goes back longer than we ever imagined.

|

|

| Approximate locations of Indo-European languages in contemporary Eurasia. Image: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. | Chart explaining Grimm’s Law. |

Further reading

- Anatole V. An introduction to the languages of the world. Oxford University Press, 1997.

- JP Mallory. In search of the Indo-Europeans. Thames and Hudson, 1989

- John McWhirter. The story of human language. The Teaching Company. Chantilly Virginia, lectures eight and nine.

GEORGE DUNEA, MD, Editor-in-Chief

Fall 2020 | Sections | Literary Essays

Leave a Reply