Henry Bair

Stanford, California, United States

|

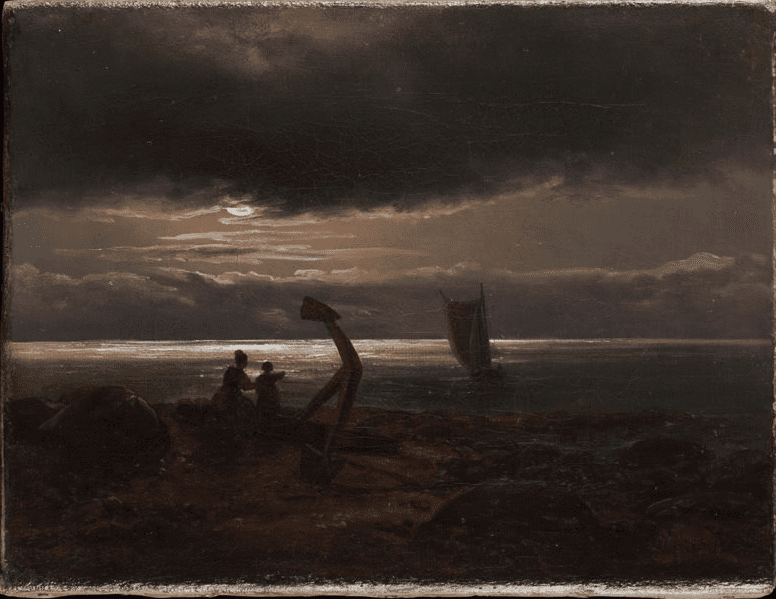

| Mother and Child by the Sea. Johan Christian Dahl. 1830. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Public Domain. |

The first time I saw a late-term abortion by dilation and evacuation, I was surprised that it was a fairly minor procedure. I was to observe the termination at twenty-three weeks of gestation as part of my obstetrics-gynecology rotation, and while the procedure can be performed in a clinic rather than an operating room, given the gestational age, considerable technique would be needed to minimize maternal harm. As the patient’s toxicology screen was positive for methamphetamine, the surgeon and anesthesiologist chose to use a spinal block rather than risk general anesthesia.

Whether or not we talk about it, offend each other, or advocate for or against one particular side, abortion remains a complex issue in a society seething with angst. The complexity and controversy are particularly intense in the case of late-term abortions, which are still illegal in many places.

Until I was involved in this patient’s care, abortion had been an abstract ethical issue for me. I had no personal or professional exposure to it and no strong value judgments per se, other than a wary curiosity about how someone could wait twenty-two weeks before deciding to have one. In retrospect, I most certainly also had some assumptions about the patient, about the “type” of person who would opt to have an abortion more than five months into a pregnancy.

My assumptions ballooned as I skimmed through her medical record and caught certain keywords leaping off the page. Chronic methamphetamine user. Homeless. Currently unemployed. Uninsured. Long-term victim of abuse by her partner. No prenatal care.

As the surgical team prepared the operating room, I wandered over to the preoperative holding area and looked for the patient. Her chart had not prepared me in any way for meeting her. Her skin was nearly covered in tattoos and she had a fresh-looking black eye, which, she told me, was from her partner. We slipped easily into conversation, and soon I learned far more about her than her medical record had revealed. Why wait twenty-two weeks? Because when you are homeless, underemployed, in an abusive relationship, and generally unwell, you might not know you are pregnant until seventeen weeks. And then you agonize.

You agonize over wanting to give your child a good life and a good chance when you know you struggle just to take care of yourself and have not been able to do so for a long time.

You agonize because you would not raise a child near illicit drugs and everything that comes with them, but you have yet to successfully pull yourself away from them for any real length of time, despite your best efforts and even though you can feel them killing you, bit by bit.

You are not certain you can protect your child from violence. You cannot even seem to stop subjecting yourself to it again and again.

She was scared to death, she said through her tears. She desperately wished abortion was not the answer, but she saw no other way forward.

“I wouldn’t be able to live with myself if I delivered this baby because I can’t provide, can’t mother, can’t even start him off with his own clean slate.” She had continued to use methamphetamines during her pregnancy, and even now could feel the effects of her most recent use. I had expected that someone making this choice would be callous or careless, but she did not seem that way at all. It was quite the opposite: she seemed tortured, haunted, and deeply thoughtful.

The patient was transported into the operating room and I supported her in a sitting position as the spinal anesthetic was placed. She was trembling, and I knew that even as the physical numbness set in, she was wracked with emotion. As the nurses laid her down, the surgeon, Dr. Hart—a tall, reserved, prayer bead-wearing man—pulled me aside and warned me to brace myself, whispering that late-term abortions can be “rather shocking” to newcomers.

He was correct. As the resident began applying the cervical dilators, Dr. Hart maneuvered the ultrasound transducer. Soon the fetus, with its distinct head and limbs, popped into view on the monitor; at the center of the body, the heart flickered in motion. The little limbs twitched. After the amniotic sac was broken, the resident swiftly reached into the uterus with a clamp and started manipulating the fetal body. I was transfixed.

Dr. Hart leaned over and remarked, “You see how gentle we are?”

The patient began to cry. The anesthesiologist looked at Dr. Hart, who shook his head, then gestured to me. “Go hold her hand.”

I did. She grasped it tightly and looked into my face.

After a few moments, the resident was able to quickly remove all products of conception from her uterus. The whole procedure was over in less than thirty minutes.

After we wheeled the patient to the recovery area, Dr. Hart offered to debrief with me. He mentioned that he had done thousands of these procedures all over the world, often in settings vastly more under-resourced than the hospital we now were in. I asked about the prayer beads around his neck, to which he chuckled and replied, “I was raised Catholic . . . but let’s just say I’m now more spiritual than religious.” I was surprised, and even more curious as to how his personal beliefs had shaped his calling.

He told me about the many women he had met in his career in similar or worse circumstances than this patient—women who saw their decisions as the only viable way to spare their babies lifetimes of misfortune and suffering. He wished, he said, that no one ever had to go through an abortion, late-term or otherwise, but saw himself as the most capable person to help individuals experiencing these terrible situations. It eventually made sense to me, a doctor doing what he could to alleviate torment.

As he stood up and got ready to see his next patient, he asked, “So how are you feeling?”

“I’m still a bit shaken, and maybe also a little conflicted. Seeing the surgery . . . affected me far more than I could have imagined.”

“Good. You know, even after all this time, I’m still affected by every single case, every patient. It keeps me grounded and reminds me of the solemnity of my work.”

Instead of helping to clarify how I feel about abortion, as I had assumed this experience would, I now find it impossible to discuss the morality of the issue in dichotomies. I had been troubled by how violent the procedure appeared, based on my technical understanding of it, and by my presuppositions about patients who make the choice to proceed with it. But having fathomed the mother’s predicament and having finally witnessed the procedure, I believe that she was right in her assessment: she would be bringing her child into a life of misery. Could she have placed the baby for adoption? Possibly. If her amphetamine use, or the physical abuse, or her lack of prenatal care and self-care did not result in miscarriage, there was still a high risk of significant birth complications, and of a medically, physically, or emotionally compromised child. The adoption prospects for these infants are generally not promising.

My empathy for this patient and the complexity of her decision have not galvanized me to be unequivocally supportive of abortion. I find myself more lost about what I think and feel, though I am comforted by my conviction that the decision she made was—as she understood it—the most compassionate thing she could have done for her unborn child.

Perhaps this is applicable to all aspects of healthcare: for many patients, the justification of our recommendations depends not just on a constellation of symptoms, but on a collection of personal judgments about a patient’s personal worldview. But understanding the nuanced ambivalence of our patients’ inner worlds means also being willing to engage with our own.

HENRY BAIR is a medical student at Stanford University School of Medicine. Born and raised in Taiwan, he is interested in cross-cultural communication in medicine as well as the intersections between medical care and literature. In addition, he is passionate about medical education, especially in end-of-life care and in improving the patient-physician relationship.

Fall 2020 | Sections | Doctors, Patients, & Diseases

Leave a Reply