Janet Ming Guo

Atlanta, Georgia, United States

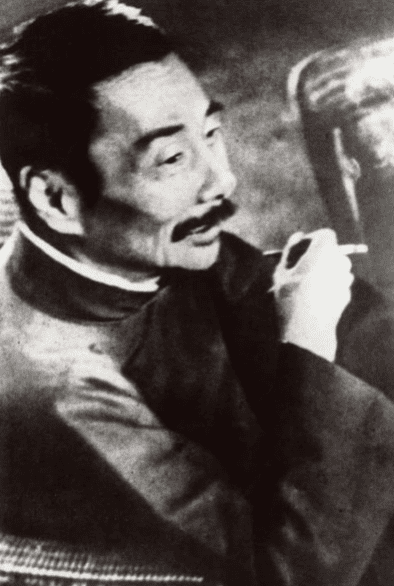

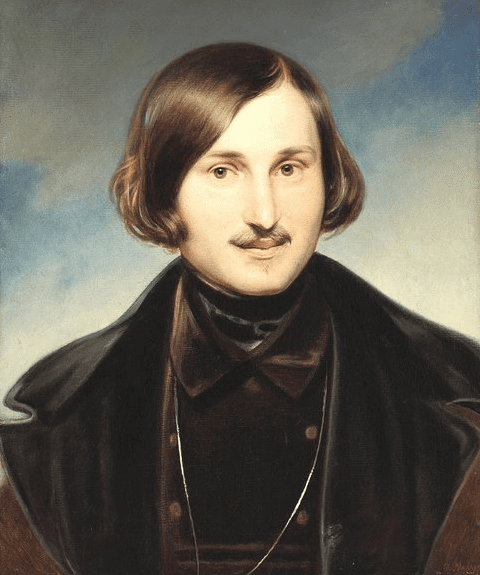

Lu Xun’s 狂人日記 (A Madman’s Diary; 1918)1 was inspired by Nikolai Gogol’s Записки сумасшедшего, Zapiski sumasshedshevo (Diary of a Madman; 1835).2 Both works reveal crucial information about schizoaffective disorder and schizophrenia, two psychiatric disorders that are often misdiagnosed3 but affect many people worldwide. In 2019 the World Health Organization estimated that twenty million people had a diagnosis of schizophrenia.4 There are few large-scale studies on the incidence and prevalence of schizoaffective disorder. Historical narratives may provide important clues about these psychiatric conditions.

The stigma associated with mental illness varies across sociocultural settings. In countries like China and Russia, mental illness is often hidden from the general public and even the person’s family, as there are heavy feelings of shame and disgrace attached to those who are affected.5-9 An epidemiological survey conducted by Phillips et al in 20095 found that as many as 92% of individuals with mental disorders in China had never sought any type of professional help. Likewise, Nersessova et al in 20196 found that the Russian participants were likely to try to deal with mental illness on their own without professional help.

Chinese citizens who are diagnosed with mental illness are often labeled as 不正常 (buzhengchang) or as a 残废 (canfei), which can lead to widespread discrimination in the workplace and in marriage and social opportunities.7 These views are rooted in many of China’s strict sociocultural norms and history that shape how mental illness is perceived. The first psychiatric hospital was opened in China by American medical missionaries in 1898, fourteen years before the beginning of the Republic of China, but many of these facilities were shut down during the Cultural Revolution.10 In fact, it has taken 114 years since the opening of the first psychiatric hospital for the first national mental health law of the People’s Republic of China to be adopted by the National People’s Congress.11

Before the Cultural Revolution, during the Republic of China (1912-1949), Lu Xun published A Madman’s Diary at a time when mental illness was an unspoken topic. This work became a cornerstone of China’s New Culture Movement of the 1910-1920s, which criticized traditional Confucian values and promoted Western ideals like democracy. This fictional narrative of a schizophrenic patient was widely read in its time and is still read by many today. The story begins from the point of view of the narrator, who had been close friends with two brothers during school. He is told that Younger Brother, the main character, suffered from a mental illness but has gotten better. The narrator is given Younger Brother’s diary from the time he was sick, and the entries revolve around the central theme that everyone around Younger Brother may be a cannibal, even Elder Brother. His paranoia increases with each entry, and he ends by asking someone to “save the children.” The treatment of Younger Brother and his condition provides some insight into how people with mental illness were treated during the Republic of China, and how these historical roots may affect the treatment of those with psychiatric disorders in modern day China.

Mental illness is also heavily stigmatized in Russia, which again has its roots in Russian history. The Ministry of Health of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) established the Psychiatry Commission in October 1917 with funds from the central government.8 While this should have been a monumental step in increasing mental health services, the reality is that efforts were widely curtailed because of limited funding and the sociopolitical isolation of the country during Soviet rule. Many people were forced into isolation for political reasons such as endorsing capitalistic ideals, rather than correctly diagnosing psychiatric diseases or learning disabilities.6,12 Patients were labeled with symptoms such as “reform delusions,” “struggle for the truth,” and “perseverance.”12 These practices set forth a delicate, unreliable, and problematic foundation for modern-day mental health practitioners in Russia, and as a result, more mental health facilities that employ unbiased practitioners are needed within the country.

Before the establishment of the USSR’s Psychiatry Commission, during the time of the Russian Empire (1721-1917) and Nikolai Gogol’s Diary of a Madman, psychiatric services had not been formally recognized by the central government. This work, considered to be one of Gogol’s best, is similar to Lu Xun’s work in that it is written in first-person through diary entries. It describes the innermost thoughts of Aksenty Ivanovich Poprishchin, a low-ranking civil servant, as he descends into what many describe as “madness” and is locked in a mental asylum. By the end of his series of diary entries, Aksenty believes he is the king of Spain. There was no formal acknowledgment of mental illness during the Russian Empire and a dearth of literature to examine how psychiatric patients were evaluated or treated during that time, which makes Diary of a Madman a landmark work.

Using the diagnostic criteria of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition (DSM-5),13 both Diary of a Madman and A Madman’s Diary would seem to have main characters with schizophrenic symptoms. Gogol’s story is more grounded in reality than Xun’s, which would be consistent with the allegorical use of mental illness with sociopolitical undertones. However, Gogol’s main character, Aksenty Ivanovich Poprishchin, also has extreme intermittent mood swings, which would be a presentation more consistent with schizoaffective disorder.14

Aksenty endorses symptoms consistent with schizophrenia, such as bizarre hallucinations and visual and auditory delusions that are in no way grounded in historical reality.15-18 However, in Lu Xun’s story, Younger Brother describes factual historical events, such as the presence of cannibalism at the time.19-21 He describes the way Elder Brother made him eat Younger Sister.19 Lu Xun was using mental illness to describe the traditional Confucian culture that drove the central government at the time22 as “man-eating,” oppressive, and backward. The society is depicted as one in which the strong overpower the weak and the weak cannot speak up. It is only when Younger Brother goes “mad” that he is able to see how bad the feudal society of pre-revolution China before the New Culture Movement really is.

This is both consistent and inconsistent with past scholarly analyses of the works. Many have found that Aksenty had symptoms consistent with schizophrenia,23-25 as did Younger Brother.26-30 However, Aksenty’s diary entries indicated extreme mood swings, which would be more in alignment with schizoaffective disorder.14 It is difficult to find evidence of major depression or mania that would indicate bipolar disorder. Neither Gogol’s main character nor Lu Xun’s main character have any evidence of suicidal ideation or self-harm. Gogol’s character does express mood-congruent delusions consistent with mania when he believes that he is the king of Spain, but besides that isolated entry, there is no evidence of other symptoms typically seen in a manic state. It is possible that Gogol’s character did have bipolar disorder, but from the text there is no way to assess all the symptoms required for this diagnosis. Other articles about Gogol’s work have proposed that the main character had features of dementia31 or schizoaffective disorder.22 Specifically, Holden writes that Gogol did a beautiful job in painting a “portrait of a bureaucrat’s descent into dementia.”31

These grand works of literature remind us that it is important to reach out and seek treatment for all mental health symptoms. In order for this to happen, the stigma must be removed from mental illness. One way to do this is through popular literature, as more narratives will help others to overcome feelings of isolation and encourage them to reach out to friends, family, and professionals for help.

Notes

- Lu Xun (1995), Selected Stories of Lu Xun (University of Hawaii Press). p. 29-41. Of note, this edition of Lu Xun’s work contains many footnotes that may be of interest to the reader related to the traditional Chinese references within the original text. Interestingly, Xun’s A Madman’s Diary was inspired by Gogol’s Diary of a Madman.

- Nikolai Vasilíevich Gogolí and Ronald Wilks (1991), Diary of a Madman (New York: Penguin). p. 1- 15. This recent edition of the short story has been translated from Russian into English and may contain some differences from the original Russian text published during the Russian Empire.

- T.J.P. Wy and A. Saadabadi (2020), “Schizoaffective Disorder.” Statperals. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31082056

- World Health Organization (2019), “Schizophrenia.” accessed September 1, 2020, https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/schizophrenia.

- M. R. Phillips, J. Zhang, Q. Shi, Z. Song, Z. Ding, S. Pang, X. Li, et al. “Prevalence, treatment, and associated disability of mental disorders in four provinces in China during 2001-05: An epidemiological survey.” Lancet 373 no. 9680, p. 2041-53.

- K. S. Nersessova, T. Jurcik, and T. L. Hulsey, “Mental health reform in the Russian Federation: an integrated approach to achieve social inclusion and recovery.” Int J Soc Psychiatry 65no. 5, p. 388-98.

- J. Liu, H. Ma, Y. L. He, B. Xie, Y. F. Xu, Y. Tang, M. Li et al. (2011), “Mental Health System in China: History, Recent Service Reform and Future Challenges.” World Psychiatry 10 no. 3, p. 210-6.

- V. Reshetnikov, E. Arsentyev, S. Boljevic, Y. Timofeyev, and M. Jakovljevic (2019), “Analysis of the Financing of Russian Health Care over the Past 100 Years.” Int J Environ Res Public Health 16 no. 10.

- Y. S. Park, S. M. Park, J. Y. Jun, and S. J. Kim (2014), “Psychiatry in Former Socialist Countries: Implications for North Korean Psychiatry.” Psychiatry Investig 11 no. 4, p. 363-70.

- N. Blum and E. Fee (2008), “The First Mental Hospital in China.” Am J Public Health 98 no. 9, p. 1593.

- W. Xiong and M. R. Phillips (2016), “Translated and Annotated Version of the 2015-2020 National Mental Health Work Plan of the People’s Republic of China.” Shanghai Arch Psychiatry 28 no. 1, p. 4-17.

- R. van Voren (2010), “Political Abuse of Psychiatry–an Historical Overview.” Schizophre Bull 36 no. 1, p. 33-5.

- American Psychiatric Association (2013), Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition (DSM-5).

- Gogol, Diary of a Madman, 3-4.

- Gogol, Diary of a Madman, 6.

- Gogol, Diary of a Madman, 7.

- Gogol, Diary of a Madman, 10-11.

- Gogol, Diary of a Madman, 13.

- Xun, A Madman’s Diary, 32-34.

- Shizhen Li and Xiwen Luo (2003), The Compendium of Materia Medica. This is an updated version of the original text which was published during the Ming Dynasty. This is widely considered one of the most complete and comprehensive written in the history of traditional Chinese medicine, which states that human flesh can be eaten under certain circumstances.

- Guanzhong (2017), Guan Zi. This is an updated version of the original text published around 7th century BCE by philosopher and statesman Guan Zhong. Younger Brother also references this ancient Chinese text which depicts a ruler who boils his son and serves him as food.

- Arthur W. Hummel (1930), “The New-Culture Movement in China.” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 152, p. 55-62.

- Altschuler, E. L (2001), “One of the Oldest Cases of Schizophrenia in Gogol’s Diary of a Madman.” BMJ 323 no. 7327, p. 1475-7. Of note, AK Chopra’s Rapid Response to Altschuler’s article raises the possibility of Aksenty’s clinical presentation of possible schizo-affective disorder.

- Dean A. Haycock (2009), The Everything Health Guide to Schizophrenia: The Latest Information on Treatment, Medication, and Coping Strategies (Adams Media).

- Matthew David McWilliams (2017), “Burning Flames and Seeing Brains: Passion, Imagination, and Madness in Karamzin, Pushkin, and Gogol.” (M.A. Thesis, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign).

- Emily Baum (2018), “Madness and Modernity.” (Alec Ash ed).

- Brian Johnson (2016), “Two Tropes in Lu Xun’s Fiction: The Sick Man and the Crowd.” (M.A. Thesis, San Francisco State University).

- Ming Dong Gu (2001), “Lu Xun, Jameson, and Multiple Polysemia.” The Canadian Review of Comparative Literature 28. Of note, both Lu Xun’s A Madman’s Diary and Nikolai Gogol’s Diary of a Madman have the same title when translated back to their original language of composition (Chinese and Russian, respectively) which further shows the direct relation between the two texts. Additionally, Lu Xun has stated in past interviews that Gogol’s work directly influenced his own writing.

- Vincent Yang (1992), “A Stylistic Study of “the Diary of a Madman” and “the Story of Ah Q”.” American Journal of Chinese Studies 1 no. 1, p. 65-82.

- J. D. Chinnery (1960), “The Influence of Western Literature on Lǔ Xùn’s ‘Diary of a Madman’.” Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies vol. 23 no. 2, p. 309-322.

- Stephen Holden (1987), “Stage: Gogol’s ‘Diary of a Madman’.” The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/1987/12/17/theater/stage-gogol-s-diary-of-a-madman.html.

Bibliography

- Altschuler, E. L. “One of the Oldest Cases of Schizophrenia in Gogol’s Diary of a Madman.” BMJ 323, no. 7327 (Dec 22-29 2001): 1475-7. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.323.7327.1475. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11751362.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition (DSM-5). 2013. doi:https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596.

- Baum, Emily, “Madness and Modernity,” Alec Ash ed., 2018.

- Blum, N., and E. Fee. “The First Mental Hospital in China.” Am J Public Health 98, no. 9 (Sep 2008): 1593. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2008.134577. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18633073.

- Chinnery, J.D. “The Influence of Western Literature on Lu Xun’s ‘Diary of a Madman’.” The Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 23, 2 (1960): 309-22. https://doi.org/10.2307/609700.

- Gogolí, Nikolai Vasilíevich, and Ronald Wilks. Diary of a Madman, and Other Stories. New York: Penguin, 1991.

- Gu, Ming Dong. “Lu Xun, Jameson, and Multiple Polysemia.” The Canadian Review of Comparative Literature 28 (2001).

- Guanzhong. Guan Zi. Hang zhou: Zhe jiang da xue chu ban she, 2017.

- Haycock, Dean A. The Everything Health Guide to Schizophrenia: The Latest Information on Treatment, Medication, and Coping Strategies. Everything Series. Original Edition ed.: Adams Media, August 18, 2009.

- Holden, Stephen. “Stage: Gogol’s ‘Diary of a Madman’.” The New York Times (1987): 28. https://www.nytimes.com/1987/12/17/theater/stage-gogol-s-diary-of-a-madman.html.

- Hummel, Arthur W. “The New-Culture Movement in China.” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 152 (1930): 55-62. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1016538.

- Johnson, Brian. “Two Tropes in Lu Xun’s Fiction: The Sick Man and the Crowd.” Master of Art in Humanities, San Francisco State University, 2016.

- Li, Shizhen, and Xiwen Luo. Compendium of Materia Medica. Beijing: Foreign Languages Press, 2003.

- Liu, J., H. Ma, Y. L. He, B. Xie, Y. F. Xu, H. Y. Tang, M. Li, et al. “Mental Health System in China: History, Recent Service Reform and Future Challenges.” World Psychiatry 10, no. 3 (Oct 2011): 210-6. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2051-5545.2011.tb00059.x. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21991281.

- Lu, Xun. Selected Stories of Lu Hsun. Doylestown, Pa.: Wildside Press, 2011.

- McWilliams, Matthew David. “Burning Flames and Seeing Brains: Passion, Imagination, and Madness in Karamzin, Pushkin, and Gogol.” M.A., University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2017.

- Nersessova, K. S., T. Jurcik, and T. L. Hulsey. “Differences in Beliefs and Attitudes toward Depression and Schizophrenia in Russia and the United States.” Int J Soc Psychiatry 65, no. 5 (Aug 2019): 388-98. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764019850220. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31159634.

- Park, Y. S., S. M. Park, J. Y. Jun, and S. J. Kim. “Psychiatry in Former Socialist Countries: Implications for North Korean Psychiatry.” Psychiatry Investig 11, no. 4 (Oct 2014): 363-70. https://doi.org/10.4306/pi.2014.11.4.363. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25395966.

- Phillips, M. R., J. Zhang, Q. Shi, Z. Song, Z. Ding, S. Pang, X. Li, Y. Zhang, and Z. Wang. “Prevalence, Treatment, and Associated Disability of Mental Disorders in Four Provinces in China During 2001-05: An Epidemiological Survey.” Lancet 373, no. 9680 (Jun 13 2009): 2041-53. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60660-7. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19524780.

- Reshetnikov, V., E. Arsentyev, S. Boljevic, Y. Timofeyev, and M. Jakovljevic. “Analysis of the Financing of Russian Health Care over the Past 100 Years.” Int J Environ Res Public Health 16, no. 10 (May 24 2019). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16101848. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31137705.

- van Voren, R. “Political Abuse of Psychiatry–an Historical Overview.” Schizophr Bull 36, no. 1 (Jan 2010): 33-5. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbp119. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19892821.

- World Health Organization. “Schizophrenia.” 2019, accessed September 1, 2020, https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/schizophrenia.

- Wy, T. J. P., and A. Saadabadi. “Schizoaffective Disorder.” In Statpearls. Treasure Island (FL), 2020.

- Xiong, W., and M. R. Phillips. “Translated and Annotated Version of the 2015-2020 National Mental Health Work Plan of the People’s Republic of China.” Shanghai Arch Psychiatry 28, no. 1 (Feb 25 2016): 4-17. https://doi.org/10.11919/j.issn.1002-0829.216012. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27688639.

- Yang, Vincent. “A Stylistic Study of “the Diary of a Madman” and “the Story of Ah Q”.” American Journal of Chinese Studies 1, 1 (1992): 65-82. https://doi.org/10.2307/44289180

JANET MING GUO is an avid reader and loves all things neuroscience related. She is a recent graduate of Emory University and is currently working as a full-time medical scribe at a primary care clinic in rural Kentucky.