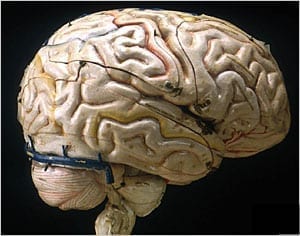

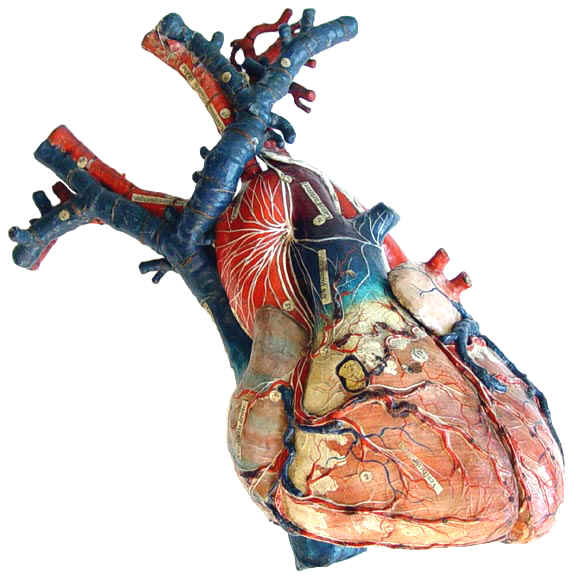

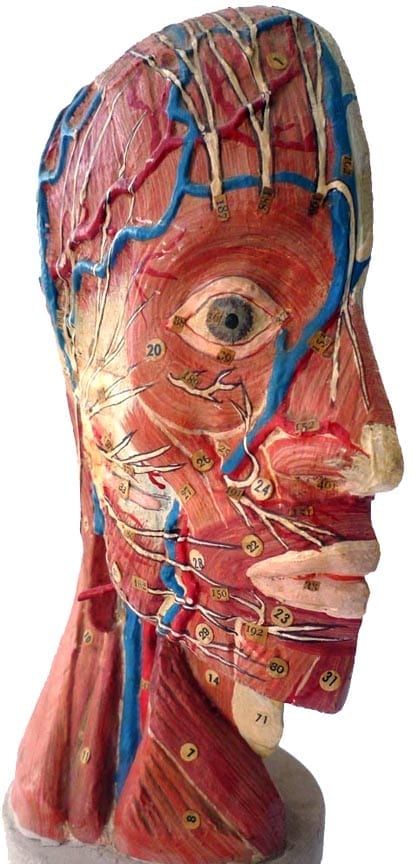

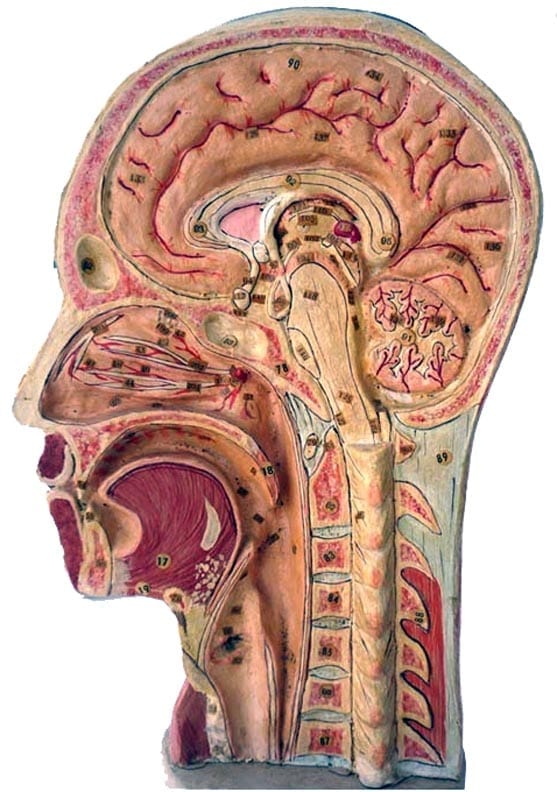

The teaching of anatomy has often been impeded by legal restrictions on dissection or by a shortage of cadavers. As drawings or paintings are generally inadequate for the purpose of instruction, some anatomists have resorted to using three-dimensional models made of materials such as wax, wood, or rubber.1-4 Thus in the early part of the eighteenth century the Sicilian clergyman Gaetano Zumbo produced anatomical models made of wax, followed by the celebrated female wax modeler Anna Morandi of Bologna, and in 1775 by the court physicist Felice Fontana of Florence. Around 1808 the French surgeon-physician Jean-François Ameline produced models that were more robust than those made of wax by taking advantage of the properties of papier-mâché and sculpting it onto real human skeletons.

Papier-mâché is an ancient technique originating from the emperors of the Han dynasty in China (BC 20–AD 220), who used it, among other things, for making helmets for their soldiers. From China, its use spread to Japan and Persia, and then to the rest of the world. It literally means chewed or mashed paper, and it consists of pulp (boiled wood) mixed with other materials such as glue, starch, cork, chalk, or textiles to produce a hard compound that can be molded into various forms. It was these properties that led the French physician Louis Thomas Jerôme Auzoux (1797-1880) to attempt to construct more resilient models.

Auzoux was the son of farmers living in the town of Saint-Aubin in Normandy. He studied medicine at the Hotel Dieu in Paris under the famous Guillaume Dupuytren and early on developed an interest in anatomy. During his training a lack of sufficient cadavers for his studies, difficulties in preserving cadavers, and the fragility of wax models stimulated him to find a better way to make anatomical models. The solution is said to have come to him when he met a woman in the street selling papier-mâché dolls; thereupon he went to Caen in 1819 to look at the work of Professor Amelie. But rather than sculpt the material on cadavers, he used it to fabricate the entire model. By 1820 he had developed a new kind of paper paste as well as a serial production process using molds. The material he used was light, not easily broken, and resistant to weather changes. The models could be easily taken apart and displayed as anatomy specimens, with added structures such as nerves and blood vessels painted by hand.2

In 1822, Auzoux displayed his first anatomical model to the French Academy of Medicine.2,3 It was a triumphant success. The government granted financial support to his modeling project, and in January 1824 put in an order for teaching anatomy in the colonies.1 In 1827 Auzoux opened a factory in Saint-Aubin to manufacture human, veterinary, and botanical models. In 1840 he even became mayor of the town.

In the following decades, Auzoux mechanized paper production and developed wood-based paper, which meant that printed matter could be produced more rapidly and cheaply, and in greater quantity, than ever before. Throughout his career, he would continually strengthen his reputation by presenting new models and submitting them to the academies of medicine and science. He followed each new model with an official report. He produced a textbook for a general audience and sent out promotional printed letters and mass mailings, reprints of favorable academy reports, prize citations, and catalogs. He also pursued more specific audiences with lectures, addressing ladies, lyceum pupils, and the military. Audiences both local and foreign flocked to his lectures, which became a must-see for Americans on their visits to Europe and also for educated Parisians like writer Jules Michelet, who considered Auzoux’s Sunday lectures the modern equivalent of attending church.4

By 1868 his factory employed more than eighty workers. A shop was opened in Paris and hundreds of pieces were sold worldwide each year. In 1832 King William IV bought a human model for King’s College London. Later Auzoux successfully lobbied for an audience with the French king; and in 1873, the Brazilian emperor made him a Knight of the Order of the Rose.4

When Auzoux died in 1880, his anatomical models had become internationally known. They remained popular and were widely used until they were replaced by more modern methods of instruction—photography and eventually computers.

sculpted by Auzoux.

Photo by Alex Peck. Source.

References

- Olry R, Wax, Wooden, Ivory, Cardboard, Bronze, Fabric, Plaster, Rubber and Plastic Anatomical Models: Praiseworthy Precursors of Plastinated Specimens J Int Soc Plastination 2000; 15, No 1: 30-35.

- Alpen Ortug A, Yuzbasioglu N. Tracing the papier maché anatomical models of Ottoman Turkish medicine and Louis Thomas Jerôme Auzoux. Surgical and Radiologic Anatomy 2019; 41:1147.

- Jarkin M. Anatomy without the gore. Lancet 2002;359:453

- Anna Maerker. Anatomizing the Trade: Designing and Marketing Anatomical Models as Medical Technologies, ca.1700–1900 Technology and Culture 2013; 54: 531. Published by The Johns Hopkins University

Leave a Reply