|

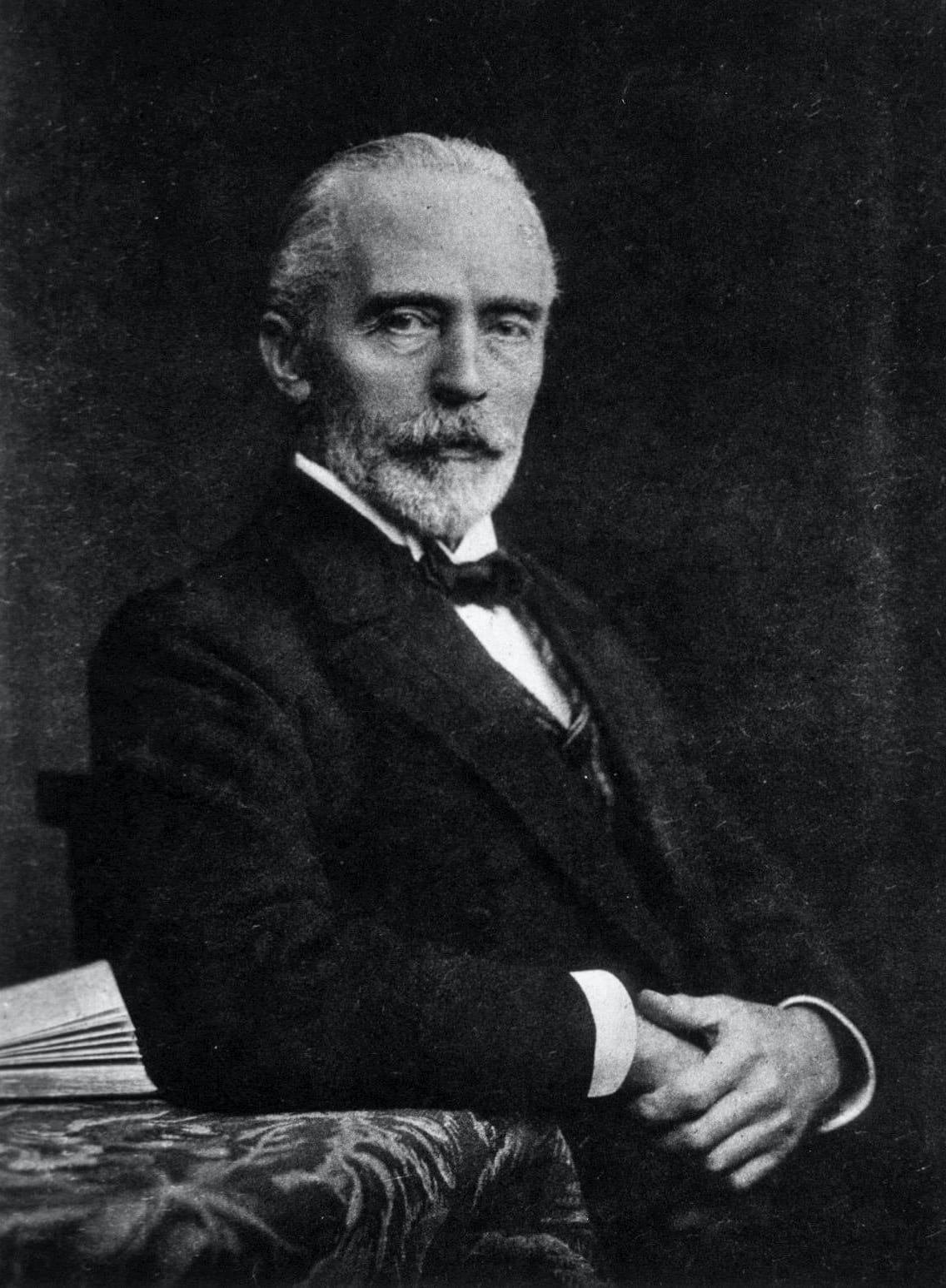

| Emil Theodor Kocher. Les Prix Nobel, 1909, p. 66. Via Wikimedia. Public domain. |

Theodor Kocher was the first surgeon to ever receive the Nobel Prize. He was born in 1841 in Bern, Switzerland, went to school there, and was first in his class. He studied medicine in Bern and graduated summa cum laude, then went on to further his education in Zürich, Berlin, London, and Paris. At the young age of thirty-one he was appointed professor of surgery and director of the university surgical clinic at the Inselspital in Bern. He remained in that position for forty-five years.1

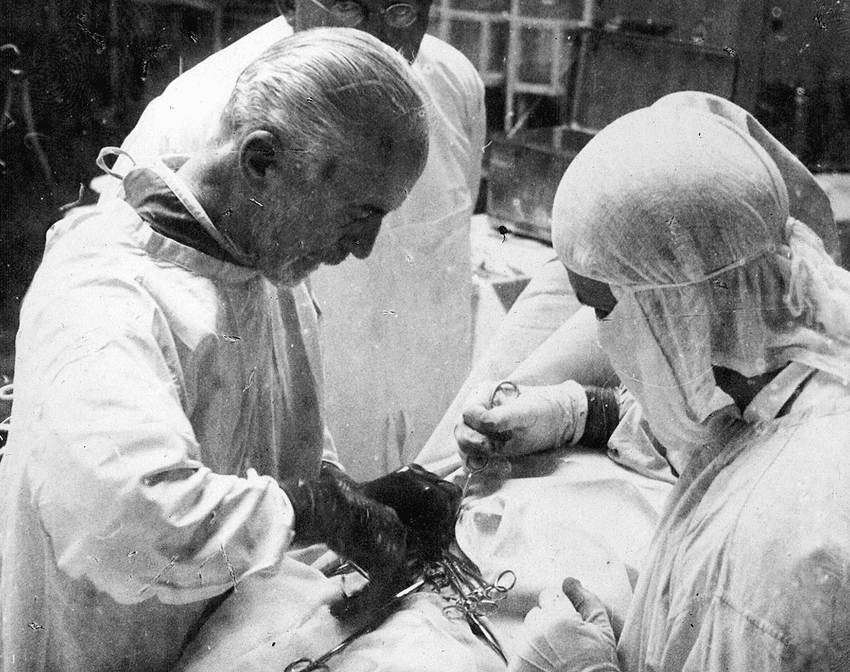

His major accomplishments, for which he received the Nobel Prize, were in the treatment of thyroid disease. This was so prevalent in Switzerland that in his time almost 90% of school children in Bern had goiters. Kocher’s surgical results were spectacular and by 1912 he had succeeded in lowering the mortality of thyroid surgery to less than 0.5%. This he achieved through strict implementation of antiseptic and later aseptic surgical techniques in the operating room and in postoperative wound care, the judicious use of general or local anesthesia, and the scrupulous avoidance of blood loss. During his career he performed over 5,000 thyroid excisions. He studied thyroid physiology and introduced thyroid hormone replacement for patients who had undergone total thyroidectomy.

Throughout his career Kocher remained a generalist and maintained an interest in other aspects of surgery. Quite early in his career he described a method for resetting the dislocated shoulder which could be done by one physician alone. He resected tuberculous foci in bones and joints, developed an interest in treating gunshot wounds, became a recognized authority in the effect of various missiles, was a colonel in the Swiss army, and gave lectures to Swiss soldiers. He made advances in the treatment of osteomyelitis, strangulated hernia, abdominal surgery, gallstones, peptic ulcer, ileus, and diseases of the male sexual organs. He pioneered methods for treating cancer of the tongue and jaw, and worked on injuries of the brain, vertebral column, and spinal cord.

Kocher’s interest in neurosurgery, and in particular in epilepsy, was stimulated by increasing understanding at the end of the nineteenth century that specific areas of the brain exerted definite functions. On the theory that such areas could also play a role in inducing seizures, he operated to remove these epileptogenic foci, but results were mixed. By 1893 he developed the theory that increased intracranial pressure, caused by fluctuations in the production or drainage of the cerebrospinal fluid, played a role in causing or worsening epilepsy. One of his pupils was Harvey Cushing, who spent five months in Bern in 1900 and 1901, and with whom he carried out various experiments to decrease the intracranial pressure. He then tried decompressing operations such as removing parts of the dura mater or inserting a drainage catheter or a valve, but results were also not satisfactory.2

In the romantic world of eponymity, Kocher is remembered for several instruments he invented, including the Kocher clamp to stop bleeding in the operating room. He also developed or modified scissors, clips, and operating tables. Several surgical incisions in thyroid, abdominal, orthopedic, and brain surgery still bear his name, as does the method of resetting dislocated shoulders, the Kocher incisions for gallbladder surgery and for nephrectomy, the maneuver for mobilizing the duodenum, the Kocher methods of gastroduodenostomy, and that for inguinal hernia repair. He described a clinical syndrome of hypothyroidism in infancy or childhood and physical signs in the eyes in hyperthyroidism. Experimentally he implanted human thyroid tissue to correct the loss of thyroid function, thus becoming an early pioneer of organ transplantation.

Kocher’s voluminous textbook on surgery was translated into six languages. The first English edition, which appeared in 1895, went through several editions. In its pages, he enunciated many principles of care, the importance of asepsis, the need for making a precise diagnosis before operating, and the urgency to operate early in cases such as appendicitis before the infection had spread. He stressed the need for surgeons, and especially young surgeons, not to operate and certainly not undertake major procedures until they had gone through a long and rigorous period of training. He wrote that just as a physician is not allowed to prescribe drugs until he is thoroughly familiar with their action, so a surgeon should not be allowed to operate unless he is capable of making an accurate diagnosis. From his experience, he concluded that surgery should always be conducted under optimal conditions. If for some reason, related to the local surgeons or unwilling relatives, the patient could not be moved, he insisted that the surgeon should bring his own assistants and instruments.

Kocher initiated and oversaw the rebuilding of the famous Bernese Inselspital. He published 249 scholarly articles and books, trained numerous medical doctors, and treated thousands of patients. In 1905 he built a twenty-five-bed private clinic where he catered to wealthier patients, many from abroad. In 1913 he operated on the wife of Vladimir Lenin, Nadezhda Krupskaya. In Bern, an institute, a street, and a park bear his name. In Manchuria, a volcano has been named after him by one of his former patients on whom he had carried out a craniotomy and who was a Russian official. In 1903 Kocher was elected the first president of the International Society of Surgery and ten years later he founded the Swiss Society of Surgery and became its president. Sir Berkely Moynihan described him as the world’s greatest surgeon.

Through his friendship and connection with Halstead and Cushing, Kocher exerted a profound influence on the still-nascent American surgical profession. Halsted, a life-long friend who visited his clinic many times and whom he met on many other occasions, often in Berlin, constantly referred to him as the greatest technical surgeon of his time.3 Unlike their earlier predecessors, both Kocher and Halsted were slow, meticulous, “physiological” surgeons who treated tissues with great care and avoided excessive blood loss. After Kocher’s death, his son Albert continued his correspondence with Halstead and in one of his letters, dated August 1918, mentions that ”a very serious influenza epidemic has come from the front and does a great deal of harm in Switzerland. Since its beginning in July there are several hundreds of deaths here.”

Kocher remained active until July 23, 1917, when he performed strenuous work in surgery, developed a severe headache, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea, was forced to take to his bed, and died four days later, perhaps from uremia. In 1909 he had been awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his work on the physiology, pathology, and surgery of the thyroid gland, the eleventh person to be so honored since the prize was first instituted in 1909.

|

|

| Theodor Kocher wearing rubber gloves in July 1914. From Thomas Schlich, “Negotiating Technologies in Surgery,” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 2013;87(2):170-197. | The Theodor Kocher Institute. Source. |

|

| Architectural rendering for the new main building of the Inselspital, Universitätsspital Bern. ASTOC / PLAY-TIME, Barcelona. Source. |

References

- McGreevy, PS and Miller FA. Biography of Theodor Kocher. Surgery 1969:65:990.

- Surbeck W, Stienen MN, Hildebrand G. Emil Theodore Kocher – Valve surgery for epilepsy. Epilepsia 2012; 53: issue 12.

- Rutkow IM. William Halstead and Theodore Kocher. Annals of Surgery 1978;188:630.

GEORGE DUNEA, MD, Editor-in-Chief

Summer 2020 | Sections | Surgery

Leave a Reply