John Raffensperger

Fort Meyers, Florida, United States

Conjoined twins have fascinated humans since earliest times. Artists illustrated twins in clay, stone statues, wood carvings, and portraits. They were exhibited on stage, in freak shows, and the circus. The worldwide news media, especially the intrusive television camera, has now replaced the circus as a means of exhibiting these children and their families to the public. The surgical separation of conjoined twins has raised ethical issues: Who decides to treat severely malformed infants? Is it right to sacrifice one twin to save the other or to allocate shared vital organs to the stronger twin?

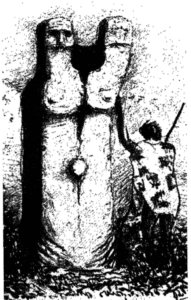

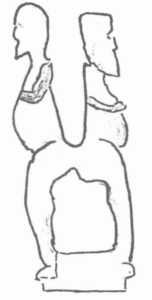

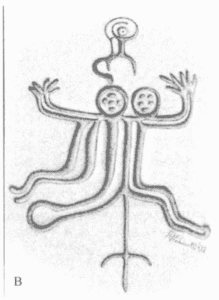

The earliest illustrations of conjoined twins were found on clay tablets in a mound near the Tigris River. These records, assembled by the Assyrian King Ashurbanipal, belonged to the Royal Library of Nineveh. A double-headed twin goddess dating from 6500 BC was also found in Turkey.1,2 There is a terracotta figure from Mexico with two heads, two arms, and two legs joined side by side in the Museo de Colón on Gran Canaria in the Canary Islands. The Museo Anthropológico on Easter Island has a two-headed figure and one of the great stone statues on Easter Island had two heads until one was taken to the British Museum.3 (fig.1) The Canterbury Museum in Christchurch, New Zealand has a wood carving of two-headed, female twins joined side by side from Easter Island. (fig.2) The wood surface has a sheen and smoothness suggesting care and long handling. The details of the carved spine are anatomically correct. The Museo de Tahiti et Des Isles has a crude wood carving of two men joined back-to-back in a sitting position, an accurate depiction of twins joined at the sacrum (pyopagus twins). A pictograph on a large stone in the courtyard of the museum shows a small woman above two-headed twins, as if she had just given birth. The twins are joined side-by-side. There are six fingers on one hand and one foot appears to be clubbed. According to an island legend, a warrior returned home to find his wife dead, probably from a prolonged labor. He carved the pictograph in memory of his wife and children. A two-headed man with a broad chest and one foot pointing backward was found in the same area as the pictograph.4* (fig. 3, a,b,c)

During the Middle Ages, physicians considered conjoined twins as monsters to be neglected or killed. They excited religious interest and many thought conjoined twins were omens of the future or God’s punishment for man’s wickedness. The first autopsy in the New World was performed on twins joined at the abdomen on the island of Hispaniola in 1553. They lived for eight days. The priest asked for an autopsy to determine which twin had the “soul” so he would know which one to baptize.5

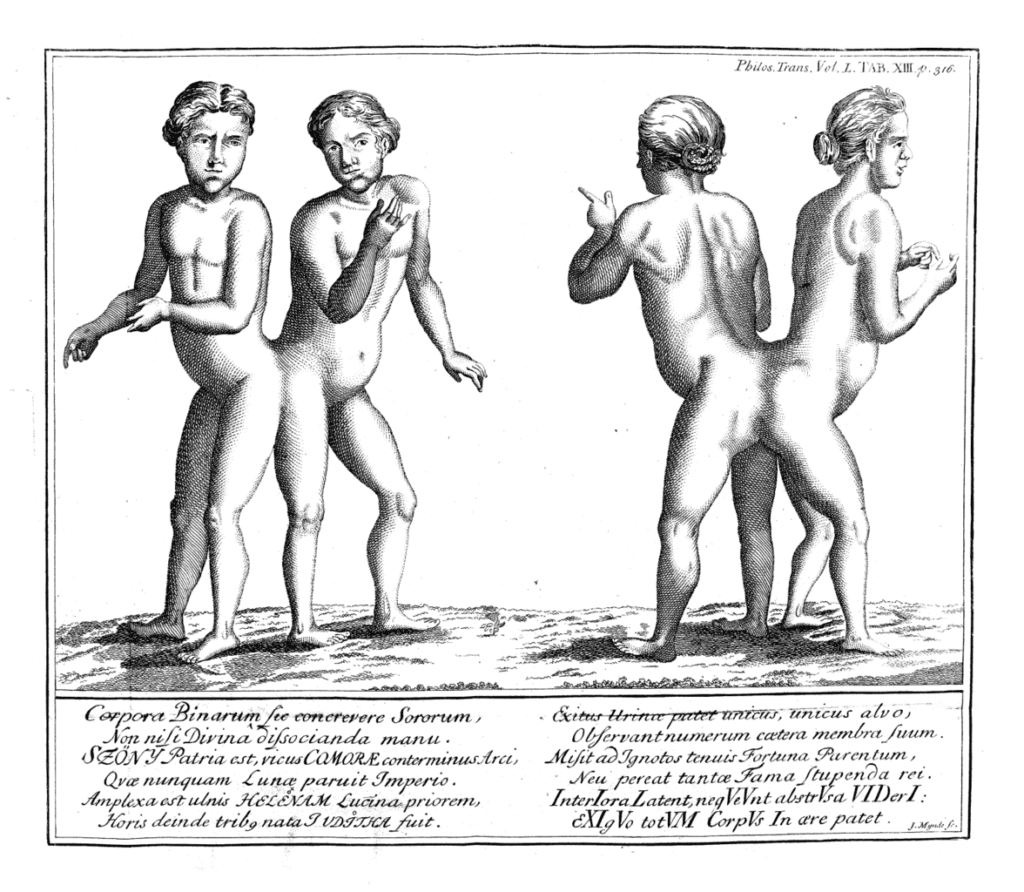

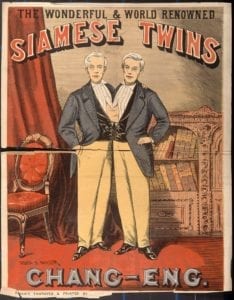

During the nineteenth century, entrepreneurs exhibited conjoined twins on the stage. The Blazek twins, joined at the sacrum, shared a single rectum and genitalia, played the violin, and sang on stage. At the age of thirty-two, one became pregnant and delivered a normal infant. Chang and Eng, the “twins of Siam” joined at the abdomen by a thin band of tissue, were exhibited in P.T. Barnum’s circus. They became successful farmers, married, had children, and lived to be a ripe old age. They refused surgical separation.6 [fig. 4,a,b,c ]

Early attempts at surgical separation were on twins with minimal soft tissue connections or when one twin was in imminent danger of death. There were increasing numbers of separations during the twentieth century with survival.7 The success of these operations fanned the public’s morbid interest in human suffering. The media, especially television, feeds on this interest with sensational stories that invade the privacy of families and patients. The media may well have influenced the family to seek surgical separation in twins who shared a six-chambered heart and were ventilator dependent. Physicians at the Loyola Medical Center in Chicago and their consultants discouraged surgery and advised the family to withdraw ventilator support and provide humane care. The family, addicted to media attention, insisted on transfer to another institution and surgical separation. Neither twin survived the heroic operation.8

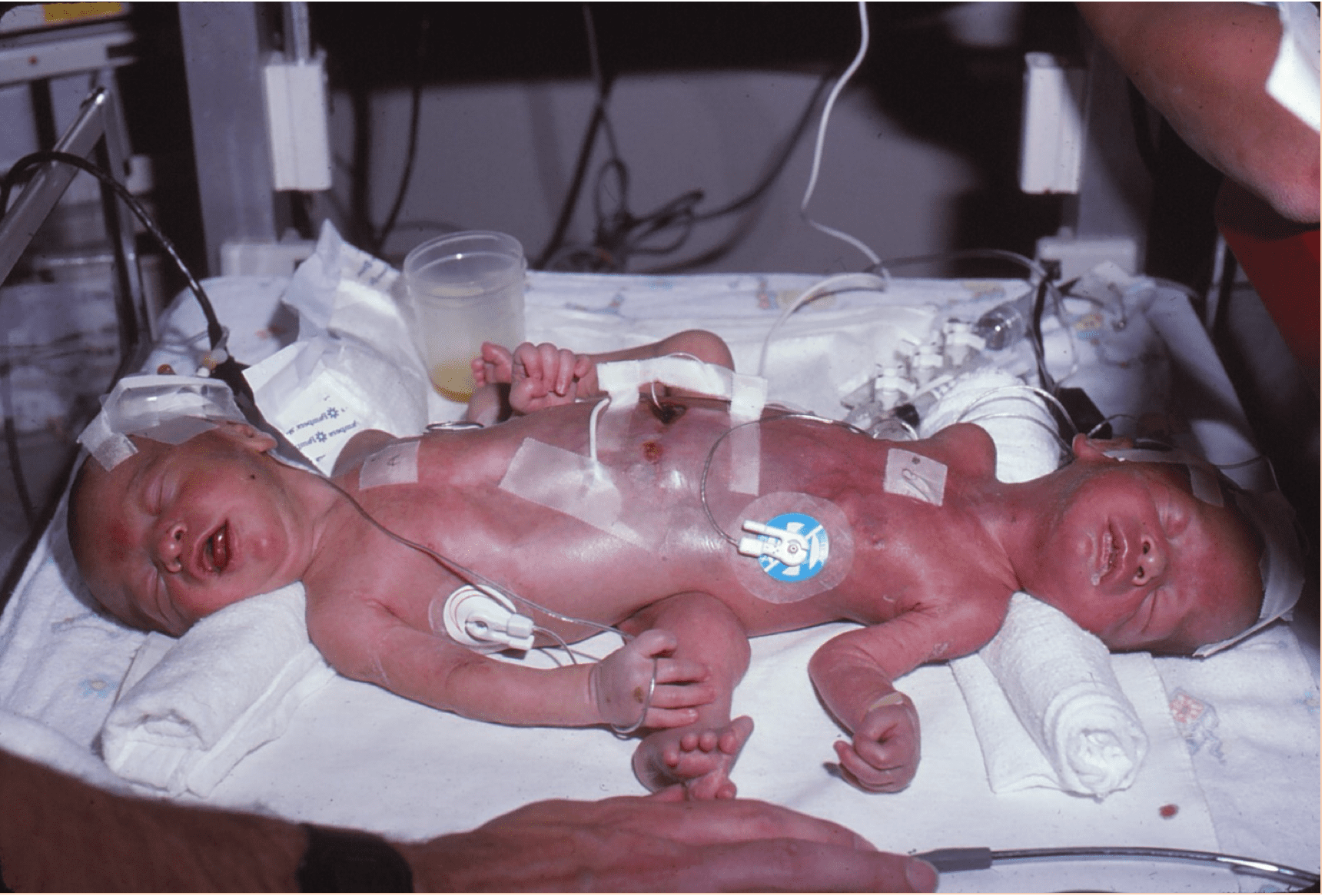

In 1981, twins joined at the perineum with heads at either end and three legs at right angles to the body were born by Caesarian section. They shared a single rectum and single external genitalia. The umbilical cord was around the neck of the smaller twin, who had congenital heart disease and was neurologically impaired. The father, a physician, the mother, a nurse, and all the physicians involved did not think the twins could survive and advised supportive care only. A hospital employee leaked news of the twins to the press and the state’s attorney. The media seized the story and the state’s attorney charged the parents with attempted murder. The state took custody and transferred the twins to the Children’s Memorial Hospital in Chicago. With ventilator support and intravenous nutrition, the larger twin thrived but the smaller twin had bouts of congestive heart failure. The media continued to harass the family and the parents divorced. The mother regained custody when the twins were a year old. I discussed surgical separation and allocating essential shared organs to the stronger twin. The mother agreed.

Many separations of conjoined twins involve elaborate preparation, special consultants, and considerable publicity. To avoid further media coverage, we treated the separation as an ordinary operation, forbade spectators and photography in the operating room, and minimized the number of operating personnel. Despite these precautions, as the last suture was tied a member of the press was called by telephone to the operating room. I refused to talk with him, but later a line of TV trucks were parked like vultures on Fullerton Avenue.

The smaller twin survived in a vegetative state for three years and died with congestive heart failure. The stronger twin required many orthopedic procedures, including amputation of the poorly functioning shared leg and fitting with a prosthesis. He attended college, took part in sports, and now is active and employed. He and his mother continue to suffer emotional wounds inflicted by media harassment.

Our team separated a similar set of female twins. The smaller twin had severe encephalomalacia. The family agreed to allocate essential organs to the stronger twin, but asked that every effort be made to ensure survival of both twins. The weaker twin survived for several months. The larger twin required further intestinal surgery, but completed college and graduate school.

We also cared for two sets of twins joined at the chest with shared hearts. There was no possibility of separation and after discussion, the parents agreed to withdraw support. The media was not involved in these three sets of twins. The families made their decisions in peace.

A fifth set of twins were joined at the abdomen and shared livers. One twin, the smallest, had an intestinal obstruction, an omphalocele, and a patent ductus arteriosus. We separated the twins with the same precautions to avoid publicity as before, but the hospital public relations department insisted upon a press conference immediately following the operation. At the insistence of the administration, one surgeon attended the meeting. She said the operation was “routine.” The press lost interest. Both twins thrived.

This small series of patients illustrates several ethical problems. Willis Potts, a humanitarian and pioneer pediatric surgeon, reiterated the long-held practice that the parents, with the consultation of family, physicians, and religious advisors should decide on the treatment for severely deformed infants. Catholic theologians supported his decision.9

Civil administrators, the courts, and finally federal law took over these critical, heart-rendering family decisions when in 1984 the Reagan administration enacted the “Baby Doe” laws after parents and a physician provided only supportive treatment rather than surgery for an infant with Down’s syndrome and esophageal atresia. The second patient was an infant born with a high spinal bifida. This law required hospitals to report “abuse” anytime treatment was withheld, no matter how hopeless the prognosis.10 The law was overturned, but the issue remains unresolved.11

The decision by the parents and physicians in our first patient appeared to be correct at the time, but the medical boundaries continually change. At this time, separation of ischiopagus twins is possible with the expectation that one twin will thrive. On the other hand, supportive care, not surgery, is the best decision for twins who share a heart.

In almost every set of conjoined twins, especially the ischiopagus variety, one twin is weaker and has associated lethal congenital anomalies. The stronger twin supports the weaker.12 In this situation, philosophers and theologians agree with sacrificing one twin to save the other and the allocation of vital organs to the twin who is most likely to survive.13 The decision, however, rests on what is surgically possible.

Rock art, statues, and wood carvings—the media of the past—did not influence medical decisions or patient privacy. Today the press and television have replaced freak shows and the circus. Doctors, hospitals, and other medical personnel may originate this media attention for personal publicity or a hospital’s desire to raise funds. Ethicists have not but should address this problem. Perhaps an addition to the oath must forbid all discussions of patients’ health issues with the press.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Figure 1. The two-headed moai at Vinapu. From Reports of the Norwegian Archaeological Expedition to Easter Island …, Volume 1. Via The Internet Archive. | Figure 2. Moai Aringa from Rapa Nui. The carving is part of the John Macmillan Brown Collection; Christchurch, New Zealand. Courtesy of Roger Fyffe, Emeritus curator, Canterbury museum | Figure 3a. Carving in the Musees de Tahiti et des Isles. Back-to-back union at the sacral area is typical for pygopagus union. Sketch by the author. | Figure 3b. Drawing of artifact from the Musee de Tahiti. There may be six fingers on the hand to the right and a possible club foot on the left leg. These associated anomalies would be in keeping with conjoined twins. | Figure 3c. Two heads on a single broad chest, collected from Matavai Bay, Tahiti, in 1822. | Figure 4a. Pygopagus twins. Two depictions of Helen and Judith of Szony from Volume 50 of Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society (1757). Via Wikimedia. | Figure 4b. Parapagus sisters with separate torsos. The juncture can include the entire chest. | Figure 4c. Chang and Eng Bunker were Siamese-American conjoined twin brothers who were widely exhibited as curiosities, they were “two of the nineteenth century’s most studied human beings”. Image: Chang and Eng, the Siamese twins, in evening dress. Colour wood engraving by H.S. Miller. Credit: Wellcome Collection. (CC BY 4.0) | Figure 5. Ischiopagus twins, separated at the Children’s Memorial Hospital, 1982. Photograph by the author. |

*Author’s note; I visited the Canary Islands, Easter Island, Tahiti and New Zealand during post-retirement sailing trips.

Reference

- Warkany, J. Congenital Malformations, Notes and Comments, Year Book Publishers, 1971, 6-9

- Schummacher, G.H. Hartman, V.N., Trivedi, P., Gill, H.; Historic Documents Concerning Craniopagi and Conjoined Twins, Gegenbaurs Morphology Jahrbook, Leipzig, 1988, 541-555

- Observed by author, October, 1998 and November 2000

- Barrow, T., The Art of Tahiti, Thames and Hudson, London, 1979, 47

- Chavarria, AP, Shipley, PG, The Siamese Twins of Hispianola; Annals of Medical History, 1924, 6, 297-302

- Luckhardt, A, Report of the autopsy of the Siamese Twins together with other Interesting Information covering their life; Surgery, Gynecology, Obstetrics, 1941, 72, 116-125

- Hoyle, RM, Surgical Separation of Conjoined Twins; Surgery, Gynecology and Obstetrics, 1990, 170, 549-561

- Paris, JJ, Ethical Issues in separation of the Lakeberg Siamese Twins; Journal Perinatology, 1993, 13, 423-424

- Potts, WJ, The Surgeon and the Child; W.B. Saunders and Co. 1959, Philadelphia and London, pgs. 5-9

- Annas, GJ, The case of Baby Jane Doe, Child Abuse or Unlawful Federal Intervention; American Journal of Public Health; 1984, 74, [7] 727-729

- White, M. The End at the Beginning; The Ochsner Journal, 2011, 11, [4], 306-316

- Spencer, R. Conjoined Twins, Development Malformations and Clinical Implications; The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003, Baltimore and London, pgs 61 and 187

- Cummings, BM, Paris, JJ, Conjoined Twins, Separation leading to the Death of One Twin: An expanded Ethical Analysis of Issues facing the ICU team; Journal of Intensive Care Medicine; 2018, 34, issue 1, 81-84

JOHN RAFFENSPERGER, MD, is a retired pediatric surgeon. With his wife, Dr. Susan Luck, he separated three sets of conjoined twins at the Children’s Memorial Hospital in Chicago. Later, while on sailing trips, he found examples of conjoined twins illustrated in stone and wood carvings. These experiences led to this examination of the media’s intrusion and influence in medicine.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 13, Issue 1 – Winter 2021

Leave a Reply