Vincent P. de Luise

New Haven, Connecticut, United States

“. . . There is no more human a picture in the entire range

of Quattrocento painting, whether in or out of Italy . . .”

– Bernard Berenson

Among the defining characteristics of the Renaissance were humanism and naturalism. While many Renaissance paintings and sculptures were depictions of religious or mythological themes, the spirit of the Renaissance hewed toward inquiry and realism. In Domenico Ghirlandaio’s Portrait of an Elderly Man and Boy (Fig. 1), we gaze upon a splendid example from the oeuvre of an artist who transcended painting metaphors and symbols to paint reality. The art historian Bernard Berenson wrote of this work that “there is no more human picture in the entire range of Quattrocento painting, whether in or out of Italy.”1,2

Domenico Ghirlandaio (Domenico di Tommaso Curradi di Doffo Bigordi, 1448–1494) was one of the most successful portrait painters of the Florentine Quattrocento. He oversaw a large and successful studio which included his brothers Davide and Benedetto, his son Ridolfo, and which trained many younger artists such as Michelangelo.2 The Renaissance biographer Giorgio Vasari said of Ghirlandaio that “from his talent and the greatness and the vast number of his works, he may be called one of the most important and most excellent masters of the age. . . .”; and the art historians Archibald Joseph Crowe and Giovanni Battista Cavalcaselle went on to comment that “Ghirlandaio’s life forms, like those of Giotto, one of the great landmarks in the history of Florentine art.“1,3 Ghirlandaio depicts the face of the elderly man with all its faults—“warts and all.” He presents the portrait in a naturalistic and sympathetic fashion, at variance with the physiognomic theory of the era, which maintained a connection between external appearances and internal truths.1 The picture portrays an older man in a red robe, embracing a young child also wearing red. They sit in an interior, illuminated against a darkened wall. Behind them at right is a window through which can be seen a landscape, its uneven terrain and winding roads typical of Ghirlandaio’s backgrounds.1,2

Whereas the Renaissance view of the old man was to focus upon his “old age-ness,” Ghirlandaio elevates the man’s wizened face and deformed nose to a tender moment where the elderly man and the child share a common bond—perhaps they are related, a grandfather and grandchild. In fact, the Italian name for this painting is very specific: Ritratto di un vecchio e nipote (Portrait of an old man and grandson (or nephew). The Italian word nipote can refer either to a grandchild or a nephew).

Rather than implying a defect of character, the portrait invites an appreciation of the elderly man’s virtuousness.1,2 The painting depicts a moment of intimacy between the elderly man and the child, underscored by the placement of the child’s hand on the old man’s chest, and the old man’s gentle expression. This show of affection endows the picture with emotional qualities beyond those expected from a traditional dynastic or commemorative portrait.1

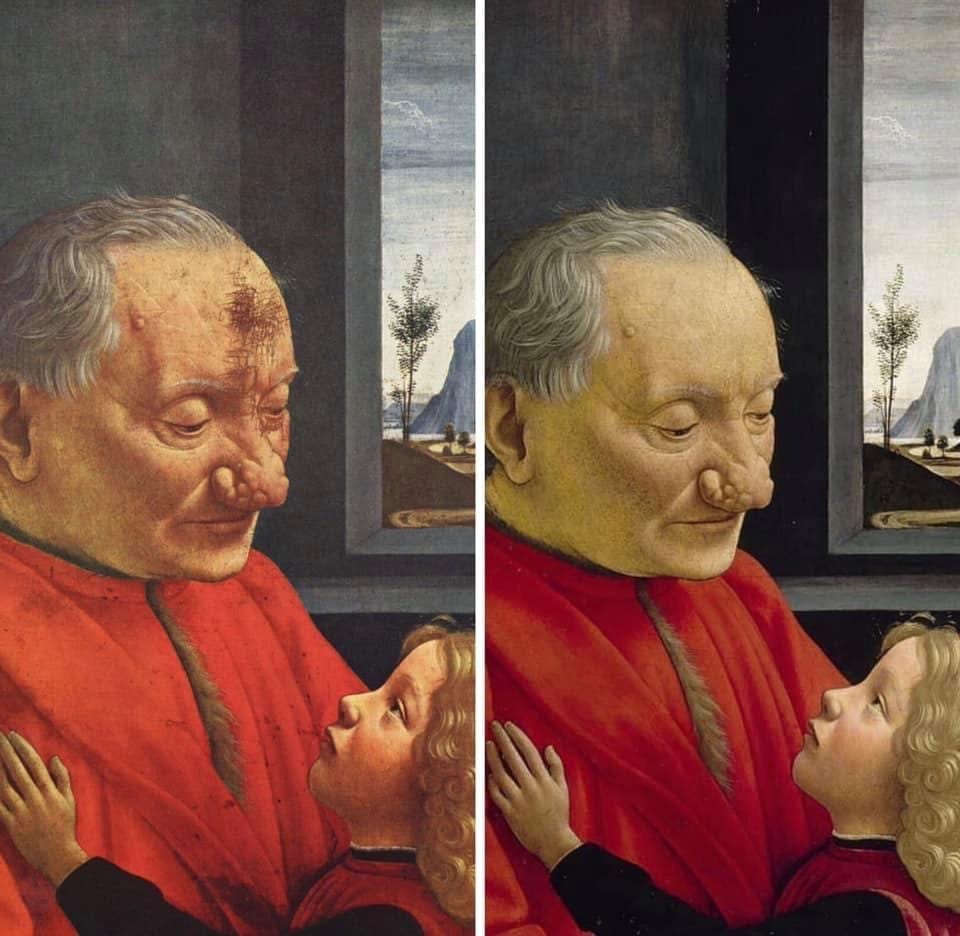

The realism in this portrait is so accurate that it is used to demonstrate to medical students and residents the manifestations of oculocutaneous rosacea (Fig. 1). The ruddy cheeks and the finely detailed periocular telangiectasias are hallmarks of oculocutaneous rosacea (detail to Fig. 1) The nasal carbuncular changes in this painting and in another portrait by Ghirlandaio of the same elderly man display a textbook image of rhinophyma (Fig. 1 and Fig. 2). Before the 1996 restoration, it was also thought that the old man’s left upper forehead displayed the cutaneous residua of a herpes zoster ophthalmicus eruption (first division of the trigeminal nerve) (Fig. 3).

References

- Cadogan, Jean K. Domenico Ghirlandaio: Artist and Artisan. New Haven and London: Yale UP, 2000.

- Louvre catalogue entry of Ghirlandaio’s Portrait of an Elderly Man and Young Boy. https://www.louvre.fr/en/oeuvre-notices/old-man-young-boy.

- Christiansen, Keith, and Stefan Weppelmann, eds. The Renaissance Portrait: From Donatello to Bellini. Metropolitan Museum of Art, distributed by Yale UP, 2011. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/metpublications/The_RenaissancePortrait_From_Donatello_to_Bellini.

VINCENT P. DE LUISE, MD, FACS, is an assistant clinical professor of ophthalmology at Yale University School of Medicine, a distinguished visiting scholar at Stony Brook University School of Medicine, and on the adjunct faculty at Weill Cornell Medical College where he serves on the Music and Medicine Initiative Advisory Board. Dr. de Luise is a senior honor recipient of the American Academy of Ophthalmology (AAO) and physician program co-chair of the Connecticut Society of Eye Physicians. A clarinetist, Dr. de Luise is a cultural ambassador of the Waterbury Symphony Orchestra and president of the Connecticut Summer Opera Foundation and writes frequently on music and the arts.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 12, Issue 4 – Fall 2020

Leave a Reply