Miriam Rosen

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, United States

|

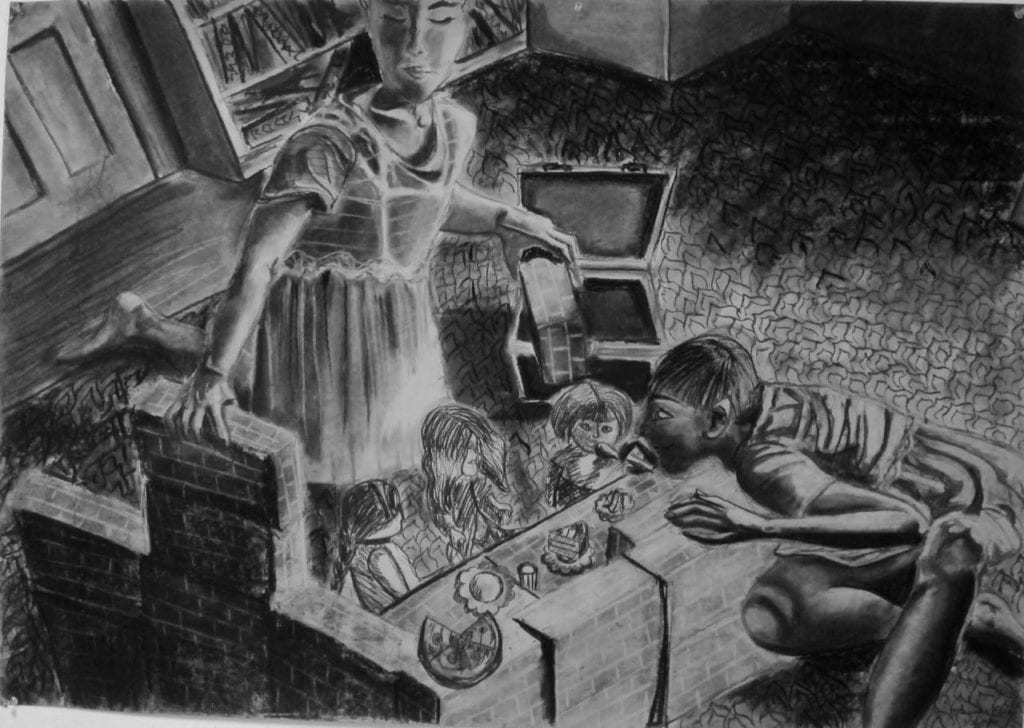

| Child’s Play by Miriam Rosen |

My mother was diagnosed with cancer when I was fourteen. For the next nine years, she lived her life with elegance and seemed to do it with ease. She continued her psychiatry practice, only gradually reducing the number of patients she saw. She read the New York Times cover to cover daily, and delved into cookbooks for new recipes as if at an excavation site. She allowed so little disruption of our family life that I began to believe her cancer was a chronic, rather than terminal, illness. Only after her death did my father tell us that her original prognosis had been limited to months, not years.

During that time, there was so much Mom wanted to talk about: what classes my friends and I were taking in college, why I chose certain fabrics for a quilt I was sewing, the stories told at an open mic event that she could not attend. She offered her attention generously, and our relationship revolved around conversation. Yet when it came to her cancer, there was a silence that I was too scared to break.

From my perspective, the only sign of illness was her hair loss. Mom hailed from a long line of proud redheads. At fifty-four, her shoulder-length hair was still a rich auburn. Soon after she started chemotherapy, strands of red hair began speckling the bathroom floor, clinging to her sweaters, and showing up in our food. One day, she came down to breakfast wearing her new wig for the first time. I hated that wig. The hair was too orange, too shiny, too long. She did not look like my mother.

I believed I could track the changes in her hair to gauge how sick she was. At my college graduation she seemed particularly ill because she had developed a slight bald spot on the back of her head. Still, I did not ask how she felt about losing her hair. Doing so would have crossed the boundary she had established with her silence.

During my first semester of medical school, Mom’s cancer spread to her brain. I felt out of place, isolated from my peers, and disengaged from classes. I left school and she died two months later. When I returned to school after a year away, I wanted to better understand the psychological toll of hair loss from chemotherapy and devoted my medical school scholarly project to this topic. I interviewed four women diagnosed with breast cancer who had lost or would soon lose their hair to chemotherapy—Sally, Jess, Pamela, and Kara.

Sally, a forty-one-year-old devoted mother of two, defined herself by her long and curly blond hair. She pulled out an old driver’s license to show me her picture. Now she wore her wig everywhere except occasionally at home with her husband and children. “Will I lose my hair?” was the first question Sally had asked her surgeon.

Hair loss was also the first and greatest fear for Jess. Just four days before her diagnosis, her boyfriend had proposed at the big fountain on the edge of the river. At her first appointment, she learned that she would lose her hair. Jess sped to a local hairstylist who specialized in fitting wigs for people with cancer. The wig was scratchy and uncomfortable. By the time her hair had completely fallen out, winter was approaching and she opted to wear a simple cap instead.

Pamela, a tough and tattooed casino boss, was diagnosed at the age of fifty-four. Like Jess, her first reaction was to find a beautiful wig. She handed over five hundred dollars, put the wig on right there in the store, and drove home. When she arrived, she took the wig off, threw it in a box, and never wore it again. From that moment, she went everywhere bald. “Bald was more me than the wig,” she said.

Kara cut her hair short in anticipation of losing it. Every night she would examine her pillow to see how much hair had fallen out. She had not yet decided whether or not she would wear a wig, but was leaning away from the idea. She did not want to look like a Halloween costume, yet the idea of being bald at the grocery store, or church, or her daughter’s cheerleading practice terrified her. She and her daughters had already picked out a few colorful caps.

I began to sense a disconnect between my own preconceptions and the lived experiences of these women. Hair loss came first, but their focus quickly shifted to other losses they would endure. Kara could no longer swim or kayak in the river with her daughters, and she had to stop tucking them in at night because she was immunocompromised. Seven years earlier, Pamela had been told that she had five years to live. Now she lives in fear that every year will be her last. Jess, at twenty-three, ceased menstruating and has given up the dream of having children.

Even Sally, who vocalized the strongest feelings about her hair loss, had more pressing concerns. She used to be the “fun one” in the family but knows she can never be as carefree and happy as she once was. She lives in fear that she will not see her children graduate, get married, and have their own children.

As Sally, Jess, Pamela, and Kara brought me closer into their lives, I felt more distant from my own mother. For me, her hair loss and its re-growth had defined her illness. I now find it unlikely that she shared this perception. The weekend before she died was the first and only time we talked about the possibility of her not being here for my graduation, my wedding, or the birth of my children.

I set out to write about hair loss, but I realize now that those stray wisps of red hair were just the beginning. As I replay conversations with my mother over those nine years, I appreciate how one-sided they were. In speaking to other women, I understand that I had been seeking the real, intimate, and painful conversations I will never get to have with Mom. As Sally told me through tears, “Too much goes on in your head. I would hope that I could be somewhat close to what I was, but I won’t ever be the same.” Mom never talked to me like this, never acknowledged how cancer tugged at her identity and changed her.

The weekend before she died, Mom and I were at the kitchen table finishing breakfast, licking the spoons from the jars of jam and sipping the remains of lukewarm coffee. “We might not get to go away this summer,” she apologized. “Of course,” I said. “That’s alright.”

Looking back on this moment, I can see that she held herself responsible for being sick. But she also felt cheated of the life she deserved and did not want to waste her remaining time indulging her illness. For me, her death seemed fast and unexpected. I do not think it had to be that way. If I could go back, I would choose to live through her uncertainty together, rather than tracing stray wisps of red hair alone.

Disclaimer: Names and details have been changed to protect the privacy of the women interviewed.

MIRIAM ROSEN majored in visual art and art history for her undergraduate studies, and is currently a fourth-year medical student at the University of Pittsburgh. Motivated to integrate the arts and humanities with the sciences, she strives to connect the two disciplines through narrative medicine. She also has a passion for pottery & ceramics, sewing, reading, and baking. While pursuing a career in psychiatry, she plans to continue her work in narrative medicine.

Spring 2020 | Sections | End of Life

Leave a Reply