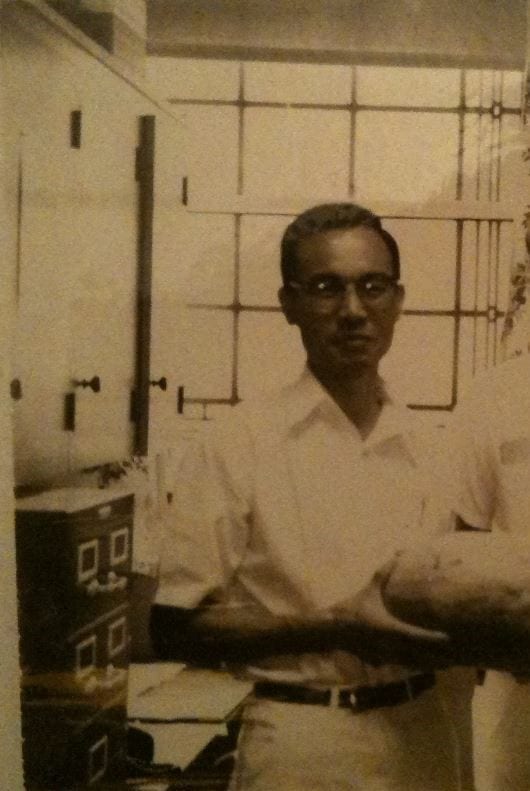

Of all the pioneers who made hemodialysis a reality, Satoru Nakamoto was the most humble and unassuming. He died in 2020 at the age of 92, almost forgotten by a generation that often takes the technical advances of dialysis for granted and rarely looks back on the people who made it possible.

I had the privilege to work in 1964 in the Depatment of Artificial Organs at the Cleveland Clinic where Sat was second in command. Several other fellows in training were there, some from the United States and quite a few from abroad. These were heady days, dialysis was still something quite new, and from all parts of the world doctors came to visit and see how it was done. Sat was held in high esteem, as one of the few who had been present in the early days when they constructed the first disposable “artificial kidney” with household equipment, little support, and doubtful prospects. Sat was always enthusiastic, optimistic, full of cheer, and friendly to everyone. Although Dr. Kolff was department head, it was Sat who spent most of the time with the fellows and visitors, teaching them the various aspects of hemodialysis and kidney transplantation.

He had been born in 1928 in the Yamaguchi prefecture in Japan, and received his medical degree from Yamaguchi Medical College after World War II. In 1953, on completing his medical studies, he went to Hawaii, took a medical internship there, and married his life-long companion Grace. He often reminisced how he found some aspects of American life puzzling, like the notion of sending children to Sunday school; he adapted, but all his life retained the old-fashioned characteristics of politeness, humility, and respect for traditional values. In July 1956 he went to the Cleveland Clinic as a Japanese exchange fellow in the Department of Artificial Organs of Dr. Willem J Kolff. After completing his fellowship he joined the staff of the Clinic and remained during his entire medical career. After retiring from the Cleveland Clinic he returned to Japan for two years to provide medical care in gratitude for his medical school training.

The initial “disposable artificial kidney” of Dr. Kolff was made by winding commercial cellophane tubing around a core of a soft drinks’ cans—beer not being allowed at the Clinic. The loops of cellophane were separated by spacers. At first there were many obstacles to be overcome. Even connecting the wider cellophane tubing to the much narrower blood tubing presented a challenge. The pressure in the dialysis circuit had to be checked manually by feeling the resistance in the arterial and venous blood chambers. Fresh dialysate was prepared before each treatment by the fellows by adding dried chemicals and topping it off with lactic acid from a test tube. There were only two Kolff tanks in the “kidney room” at the Cleveland Clinic, plus a larger tub for overnight dialysis, so the number of patients treated was very small.

The devices for establishing vascular access were also made in house. In the early days it had been necessary to cut down on the vessels for each dialysis, clearly limiting the times a patient could be treated. Later subcutaneous cannulation with Shaldon catheters was introduced. The breakthrough came with the invention of the Scribner shunt. This was manufactured in-house by technicians and fellows from Teflon and silastic tubing. When fully assembled, the shunt was connected to the forearm blood vessels by means of a cutdown that was also done by the fellows.

A cadaver kidney transplant was started in 1963. Results were dismal in the first year because the patients were over-immunosuppressed. This soon improved and by 1964 we were only one of the four institutions having successful cadaver transplant units in the United States. Most transplant programs had abandoned cadaveric kidney transplantation because of a high mortality. Sat came up with the idea of intensive dialysis treatment after cadaveric transplant until the kidney function improved and this led to a major improvement in outcomes. Because of this, Cleveland Clinic, for many years, had one of the largest groups of cadaveric transplant patients in the world. As a result many of the early trials in kidney transplantation included patients at the Cleveland Clinic. Sat was in charge of the team procuring the cadaver kidneys, which he insisted had to be removed in what he called “in block.” The harvesting was done by the fellows, often in the middle of the night. The kidneys were collected in small plastic bags filled with what became known worldwide as the “Nakamoto cocktail” (the forerunner to the Collins solution). In the department, preference was given to patients doing poorly on dialysis, since it was they and not the ones doing well who needed the transplant most urgently. Cross-matching was not introduced until later, and several patients who received non-compatible kidneys survived for a long time.

Sat was also part of several other programs established at the Cleveland Clinic, such as treating patients by dialysis in the homes, tissue typing for transplants, and other refinements of the procedure. He developed the idea of isolated ultrafiltration or SCUF that subsequently led to continueous hemofiltration modalities. Although his work was confined to dialysis, he was part of Dr. Kolff’s larger department that also had a team working on developing an implantable artificial heart, a project leading to the first patient being so treated several years later.

When Dr. Kolff left the clinic for Salt Lake in 1967, Sat was prepared to move with him but Kolff advised him to remain in Cleveland and continue the program that he had started. Sat became section chief of the Artificial Organs Section. Up to that time there had been three kidney sections at the Cleveland Clinic, a predominantly research section founded by Dr. Irvine Page and later continued by Harriet Dustin and Ed Froehlich; a predominantly hypertension section of Dr. David Humphrey and later Ray Gifford; and our department of Artificial Organs that for some strange reason also had its staff do all the kidney biopsies. Sat was very proficient in performing kidney biopsies and taught me to hit the needle very hard because most of the kidneys we biopsied were sclerotic from kidney failure. The clinical activities of these three divisions were eventually consolidated and Sat continued to play a large role in teaching nephrology fellows the technical aspects of dialysis as well as how to care for transplant and chronic dialysis patients. He spent a great deal of time with his transplant and dialysis patients and was particularly astute at managing clinical problems in this group of patients at a time when there was little evidence based data to guide the management of transplant and dialysis patients. We remained friends after I moved to Chicago and we stayed in contact by telephone and later by email. He visited Chicago several times and we often reminisced how Dr. Kolff was a demanding, hard task master typical of the professors of the old school. We remembered him as authoritarian, thrifty considering he was Dutch, visionary, always in command, and demanding. In his memoir Sat described, and we often talked about, how there was hell to pay if people failed to come on time to the morning report, which applied even to visitors. Everyone in the department had to take turns to discuss a subject for exactly seven minutes and no more, on any subject of his choice, even sailing. When Dr. Kolff would return from a meeting in Europe, Sat would comment that it was time to take Maalox again!

Over the years Sat made it a point to stay in touch with his former fellows and was always interested in how they were doing and asking if he could be of any help. In 2016 I had the opportunity to visit Cleveland in company of my wife and Dr. Earl Smith, who had also trained under him. We visited the Cleveland Museum of Art and discovered another facet of this wonderful man in that he was quite familiar with Asian and especially Japanese art. We planned to get together again but unfortunately it never happened. In 2020 he passed away, mourned by his family and regretted by all his friends and collaborators who never ceased to admire him.

Further Reading

Nakamoto S, Reflections on My Lifetime Teacher: Dr. Willem J. Kolff, Journal of Artificial Organs 13 February 2018