Edward Winslow

Wilmette, Illinois, United States

|

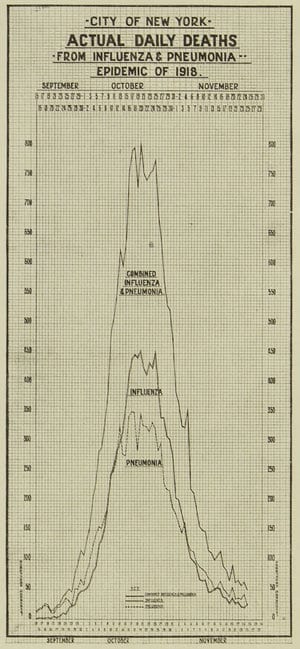

| Actual daily deaths from influenza, September to November 1918. Monthly Bulletin of the Department of Health, December 1918. NYC Municipal Library. Source. |

The 2020 viral pandemic (COVID-19),1 in spite of being caused by a novel virus family, bears striking epidemiological and social resemblance to the influenza pandemic of 1918.2 Both appeared suddenly and caused severe disease around the globe.3 The 1918 contagion is considered one of the worst in world history4 and was troubling in that no one knew what caused it. In the early twentieth century, many physicians believed influenza was caused by a bacterium (Pfeiffer’s Bacillus, also called Hemophilus Influenza—see below). Viruses were a newly discovered series of pathogens5 and were largely a theoretical construct, the understanding of which would have to wait until 1933.6 The genetic makeup of the H1N1 influenza A virus, which was responsible for the 1918/19 flu, was not defined until the last decade of the twentieth century.7 On the other hand, the causative organism for Covid-19 was identified as a coronavirus soon after the disease was recognized. An examination of the time course and of the medical and social responses to the 1918-1919 influenza pandemic might hold some insights and cautions for the present day.

John Barry8 and Susan Kent,9 among others, have written fairly comprehensive treatises on the 1918/19 influenza pandemic. They outline three distinct phases, which is believed to have started in Haskell County in western Kansas. The illness was initially considered to be a unique and somewhat harsher form of “seasonal influenza” that began just eight months after the US entered World War I. Young men were being introduced to basic training camps (cantonments) around the country. Several recruits from Haskell County ended up in Camp Funston in the Fort Riley, Kansas complex. They probably brought the flu to Camp Funston, and as men from Camp Funston went to other cantonments around the country, they took more than just their kit and rifles. They took the new influenza. In the spring of 1918, the virus mainly infected soldiers and made them quite ill, but did not seem to carry a high mortality.10 A second wave came in the fall of 1918, which was severe and had a high mortality rate, mainly among young people “in the prime of life.”

Both the 1918 flu and the current 2020 Covid-19 illnesses are viral in origin. Viruses are, for many reasons, difficult to treat, with only a few having specific drug therapies. Human Immunodeficiency Virus is one exception to this. HIV treatments, which are specific to this virus, have been successful in improving survival of people with or at risk of infection.11 Another viral disease for which there are specific antiviral treatments is Hepatitis C.12 Most viral diseases are best treated by prevention and vaccination.

Viruses can cause illness by themselves, but may also predispose to superinfections with bacteria. Other than HIV and Hepatitis C drugs, there are to date (May 2020) no medications that do much more than shorten the duration of viral illnesses. If correctly identified, a bacterial complication can be treated with antibiotics, which modifies the course of the illness. On the other hand, both bacterial and viral pathogens can be attenuated by vaccination. Today vaccines are available for seasonal influenza and other causes of serious viral and bacterial illnesses.13 Development and testing of vaccines for viruses are difficult and time-consuming.14 In 1918, vaccines against pneumococcus were being developed and appeared to be useful in decreasing the mortality of those exposed to “the flu.” The 1918 experience in Chicago suggested that people vaccinated against bacterial complications had a much more benign course than those not vaccinated.15 In the twenty-first century, it is essentially routine to vaccinate a large segment of the population with one of the pneumococcal vaccines.

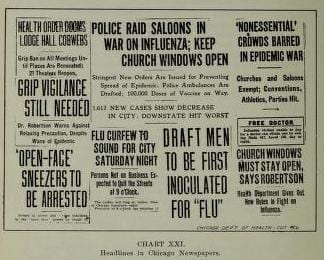

However, non-medical or public health interventions to decrease the community impact of viruses, both then and now, have the most impact. Of available interventions, interfering with person-to-person transmission seems to be the most effective with the least potential for harm. This was called “crowding control” in 1918 and “social distancing” in 2020. Recommendations for the general population to wear face coverings have been controversial in the US and Western Europe.16 Recent data suggests that they may help decrease the transmission of viruses and have a very low likelihood of harm. Face masks were recommended in many, but not all, cities in 1918 and are again recommended today. Keeping people with known disease away from others (quarantine) is also an important component of breaking the transmission chain. Optimally this requires identifying those carriers who are minimally symptomatic and isolating them, often using interventions in the rubric “test, track, and trace.”

|

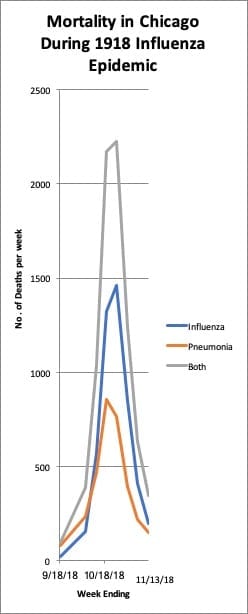

| Chart produced by the author. Data source: Dill JR, A report on an epidemic of Influenza in the City of Chicago in the Fall of 1918. Department of Health City of Chicago, 1918. |

When there is a way of identifying carriers, this sequence is fairly easy to do. If the infecting organism is not known, as in 1918, then retrospectively identifying contacts and isolating them is much harder. It is easier to find asymptomatic carriers of the virus if we can test and perform a culture. In 1918 most industrial plants, offices, and schools were kept open, but attendance at entertainment venues including theaters, dance halls, and sporting events was prohibited by public health commissioners.17 Another means of transmission of infecting organisms is from “fomite-to-finger-to-mucosa.” This suggests that wiping surfaces and frequent hand washing should also be an important means of mitigating contagions. In addition, fumigating buildings and rooms with disinfecting sprays should help interfere with viral transmission. Whether using ultraviolet or infrared lights will have an impact on sanitization has not yet been shown.

Public health initiatives are thought to work best when directed by a central source. In 1918, as in 2020, developing public initiatives that were known to be effective were delayed. In 1918, as today, the initial official response to the illness was that “it won’t be so bad.”18 However in many cases, as our understanding of the mechanism and intensity of the spread of the virus becomes more complete, public health experts have modified or walked back more optimistic assessments. The hesitancy of public health officials to sound an alarm is at least twofold. First, scientists want to be fairly sure of the accuracy of the data that might suggest one stance or another. Secondly, officials are hesitant to raise an alarm and increase society’s anxiety inappropriately. They do not want to be caught in the bind of being the “boy who cried wolf” too often. These two considerations are potentially in conflict with educating the public on potential consequences of an impending plague. In retrospect the majority of public health authorities point out that education of the public is of paramount importance. Striking the balance between generating public anxiety and fully informing the populace is very delicate.

The autumnal outbreak of the 1918 illness ran a course across the United States from early September in Boston to mid-December in Los Angeles. There was a third, unanticipated wave of the disease from January to April 1919.19

The 1918-1919 flu killed between 40 million and 50 million people worldwide, including approximately 675,000 Americans.20 It was reported to have affected about one-quarter of the world’s population. Counting those with minimally symptomatic or asymptomatic infection may have resulted in a higher estimate of the extent of the disease but lower estimates of the mortality rate. The rates for the current Covid-19 illness are yet to be determined and appear to vary in different communities. There have been suggestions that social vulnerability has been associated with worse outcomes from pandemics, both currently and in 1918. In 1918, the death rates in the British Military in India showed that the British troops had a 10% mortality while the Indian troops had an almost 20% mortality.21 Similar variations in Covid-19 mortality rates exist between socially vulnerable and more well-to-do populations in the US.22 In Chicago in 1918, on the other hand, black communities were said to do better than the general population.23 That discrepancy is hard to reconcile, and may have been related to poorer record keeping in that community.

In 1918 there was no national response to epidemics or pandemics. Medicine was just beginning to take on a scientific bent and federalism certainly superseded central government planning and control. In the early twenty-first century, on the other hand, there has been an increased understanding and reliance on forward thinking responses to problems based on planning. There have been many potentially lethal situations that have been mitigated by having a thought-out response in advance.24 In the summer of 2019, there was a federally sponsored multi-state planning exercise called the “Crimson Contagion” to test the community’s ability to respond to a respiratory virus threat. There were recommendations to improve central planning and the ability to provide needed equipment to areas of need. The report was evidently not acted upon.25

|

| From: A report on an epidemic of influenza in the city of Chicago in the fall of 1918 by John Dill Robertson. Via the Internet Archive: source |

The 1918-1919 H1N1 influenza epidemic and the 2020 Covid-19 coronavirus epidemic in the United States have many similarities. The differences in the sophistication of the medical responses then and now have perhaps blunted the severity of the Covid-19 illness. However the main responses, including isolation techniques, are similar. As of the middle of May 2020, the illness has essentially shut the country down, to a greater extent than 1918. The autumnal peak of the 1918 influenza lasted slightly longer than three months.26 There was, however, another wave in the beginning of 1919 that was lower in overall numbers but had a higher mortality. That wave almost took President Woodrow Wilson’s life while he was in negotiations to end World War I.

It would appear that central coordination and decisive action, based on the best available data—both scientific and social—would serve the country well. Reviewing contemporary reports with an unbiased eye, considering both benefits and harms of either action or inaction, are critical to optimizing a response. Armed with data such as that provided in the Crimson Contagion report, other planning documents, and the after-action reports from prior catastrophes, both potential and aborted, our responses should be able to mitigate current and future threats.

Footnotes

- The Acronym stands for Coronavirus Disease from 2019. It would almost be neater to write as CoViD-19.

- There have been many other pandemics that have affected a large part of the world as it was known at the time. (https://listverse.com/2009/01/18/top-10-worst-plagues-in-history/ ; https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/2020/local/retropolis/coronavirus-deadliest-pandemics/ )

- Kent, S.K: The Influenza Pandemic of 1918-1919: A Brief History with Documents: 2013; Bedford/St. Martin’s, Boston MA (ISBN: 978-1-319-24162-9 (ePub)

- The numbers quoted for some of the “worst” plagues are at best a little fluid. Some data suggest that the “Spanish Flu” was about the 3rd worst: Bubonic Plague (1347-1351) worst with 750,000 to 1 MM killed worldwide: and Smallpox in the “New World” in 1520 killed 56MM First Nations People. However, if we use 100MM as the worldwide death toll of the “Spanish Flu” then it is up there. https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/2020/local/retropolis/coronavirus-deadliest-pandemics/

- The tobacco mosaic virus was suspected in 1892 as a “filterable” agent. The influenza virus was not characterized until 1933, after the electron microscope was perfected.

- Barry, J.M.; The Great Influenza: The Story of the Deadliest Pandemic in History. Penguin Books 2018 and Kent op cit

- Taubenberger, J.K; Reid, A. H.; Krafft, A.E, Bijwaard, K. E., Fanning, T. G.: Initial Genetic Characterization of the 1918 “Spanish” Influenza Virus; 1997; Science, 275, 1793-6: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2892709

- Barry, J.M.; op cit.

- Kent, S.K: op cit.

- http://ocp.hul.harvard.edu//contagion/influenza.html accessed 4/16/20

- https://ccr.cancer.gov/news/landmarks/article/first-aids-drugs accessed 5/19/2020

- https://www.hepatitisc.uw.edu/page/treatment/drugs accessed 5/19/2020 https://www.healthline.com/health/hepatitis-c/evolution-of-treatments#late-zeros

- Pneumovax as prophylaxis against most dangerous superinfection is almost universal (Prevnar 13 or 23) nowadays as are vaccines to counter smallpox, measles, mumps, rabies,

- Up to the middle of 2020 the world record for development of a vaccine against a viral illness was approximately four years (https://www.nytimes.com/2013/05/07/health/maurice-hilleman-mmr-vaccines-forgotten-hero.html)

- Robertson, JD: A Report on An Epidemic of Influenza in the City of Chicago in the Fall of 1918 Department of Health City of Chicago, 1918: https://archive.org/details/reportonepidemic00robe/page/n5/mode/2up Accessed 5/15/20. P 90

- There was significant controversy as to the effectiveness of non N-95 face masks as a preventive for influenza Until new data from the 20teens and 2020.

- MacIntyre, C.R; Chughtai, A.A.: A rapid Systemic Review of the Efficacy of Face Masks and Respirators Against Coronaviruses and other Respiratory Transmissible Viruses for the Community, Healthcare Workers and Sick Patients: Int J Nurs Stud 2020 Apr 30-P 103629. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2020.103629 accessed 5/14/20

- Offeddu, V.; Yung, CF;l Low, MSF; Tom, CC: Effectiveness of Masks and Respoirators Against Respiratory Infections in Healthcare Workers: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis: 2017 Clinical Infectious Disease: 65; 1934-1942? https://doi-org.ezproxy.galter.northwestern.edu/10.1093/cid/cix681 accessed 5/14/20

- Javid, B; Weekes, MP; Mateson, NJ: Covid-10 should the public wear face masks? Population benefits are plausible and harms unlikely: 2020 BMJ; 369:m1442 doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1442 accessed 5/14/20

- Robertson, JD, op cit p. 46

- Dr. John Dill Robertson, the Commissioner of Health for Chicago is reported to have downplayed the potential hazard of the reported risks of influenza: he is reported to have said on September 24 “There is no cause for alarm whatever.” Chicago Sun Times on October 16, 2005: https://chicago.suntimes.com/coronavirus/2020/3/20/21186633/coronavirus-chicago-spanish-fluinfluenza-pandemic-1918. Public health experts today initially did not push for vigorous interventions. https://www.snopes.com/fact-check/fauci-nothing-to-worry-about/ Many times this desire not to worry people has “political” motives. In 1918, President Wilson’s government forbad discussions that would hinder “the War Effort.” Officials also don’t want to get a reputation for unnecessarily painting a “doom and gloom” scenario. Their credibility is at least partly at stake.

- There is a website housed at the University of Michigan which has a well-documented event timeline http://www.influenzaarchive.org accessed 4/11/20

- https://virus.stanford.edu/uda/ accessed 5/14/2020

- From Barry in: Institute of Medicine (US) Forum on Microbial Threats; Knobler SL, Mack A, Mahmoud A, et al., editors. The Threat of Pandemic Influenza: Are We Ready? Workshop Summary. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2005. 1, The Story of Influenza. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK22148/ accessed 5/14/20

- Villarosa, L: ‘A Terrible Price’: The Deadly Racial Disparities of Covid-19 in America. New York Times, April 29, 2020: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/29/magazine/racial-disparities-covid-19.html Accessed 5/15/20

- Robertson, J.D.: Op Cit p 99

- The fact that the recent outbreaks of Ebola has not become more of an international problem probably relates to the fact that the regions in West Africa are reasonably isolated from the rest of the world. Thomas E. Duncan evidently brought the virus to the US. He was diagnosed and treated in isolation. Two nurses who cared for him contracted the illness and were treated with isolation. They survived.

- Crimson Contagion 2019 Functional Exercise: https://int.nyt.com/data/documenthelper/6824-2019-10-keyfindings-and-after/05bd797500ea55be0724/optimized/full.pdf accessed 5/16/20. The report concluded: “Existing statutory authorities tasking HHS to lead the federal government’s response to an influenza pandemic are insufficient and often in conflict with one another Currently, there are insufficient funding sources designated for the federal government to use in response . . . It was unclear if and how states could repurpose HHS and the CED grants as well as other federal dollars to support the response to the influenza pandemic.”

- From early September in Boston until mid to late December in St. Louis.

EDWARD B. J. WINSLOW, MD, MBA, FACP, FACC. “Ted” Winslow came to Chicago, from Vancouver B.C., to be an Intern at Cook County Hospital. He did his Medical Residency and Cardiology Fellowships there and at The University of Illinois Hospitals. Since finishing training, he has spent most of his time teaching and practicing medicine while on the faculty of the Feinberg School of Medicine of Northwestern University. Since stopping active practice, Ted has developed an interest in the history of medicine, medical care, hospitals, and physicians in Chicago.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 12, Issue 4 – Fall 2020

Leave a Reply