|

| Portrait of Gaspare Tagliacozzi (1545-1599). 16th century. Collection Istituto Ortopedico Rizzoli, Bologna. Via Wikimedia. |

In his essay on Giovanni Battista Cortesi, recently reviewed in this Journal, Dr. Paolo Savoia refers to other surgeons who achieved prominence in sixteenth-century Italy. In medicine, as in the arts, progress had been abetted by an influx of Greek scholars from Byzantium after the fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Turks. In Western Europe, surgical education was undergoing a transition from poorly trained barber-surgeons to university-based surgeons; and anatomy benefited from the ingenuity of the great trailblazers from the University of Padua. The city of Bologna, part of the Papal States since 1507, prided itself on having the most ancient university in Italy, whose lecturers and professors taught surgery and anatomy to their students.

The surgeons came from diverse social classes. They were colleagues but also rivals; and they differed in their ultimate accomplishments. Members of upper-class surgical families, such as Angelo Michele Sacchi and Flaminio Rota, had lucrative private practices and no need to achieve academic renown. Those from less affluent classes had to advance their career through outstanding teaching, surgical skill, innovation, and the fame of their publications.

Among the most successful surgeons was Giulio Cesare Aranzi (1530-1589), who came from the artisan class, occupied the chair of anatomy, and at one time was receiving the highest salary from the University. He wrote on gunshot wounds, tumors, ulcers, and on the female organs of reproduction, including a treatise on the deformed narrow pelvis. He treated members of prominent Bolognese families and of the senate. According to the Polish physician Wojciech Oczko, who studied in Bologna 1565-1569, Aranzi also performed rhinoplasties and taught the technique to his students.

The Indian surgeon Sushruta has traditionally been the first to perform nasal reconstructions around 500 BC, and the procedure was mentioned by Celsus in his writings. Later it seems to have been carried out by the German barber-surgeon Pfoslpeundt (1460) and as a trade secret by the Branca families in Sicily and the Bojanos and Vineos in Calabria. Around 1558 the barber-surgeon Leonardo Fioravanti learned about it while stopping in Calabria, and on his return to Bologna wrote a book that was published in 1570. This may have helped inspire the young surgeon Gaspare Tagliacozzi.

Born in 1545 the son of a well-to-do silk worker, Tagliacozzi rose in the social ranks by receiving a good education. He learned to write and speak Latin, studied dialectics at age fifteen, philosophy at seventeen, and medicine for five years starting at nineteen, studying Avicenna, Maimonides, Hippocrates, and Galen. He acquired clinical experience at the Ospedale Della Morte and learned from Aranzi some of the techniques of rhinoplasty. In 1570 he obtained his degree in medicine, served as prosector in the anatomy department of the University, and after the death of Aranzi became one of the four professors in anatomy.

He began private practice in 1576 and soon became highly successful. He treated commoners and noblemen, the wealthy Medici and Orsini families, and the Duke Vicenzo Gonzaga of Mantua—who suffered from facial eruptions or erysipelas, and for whom he recommended and prepared special ointments. In time his salary from the University was significantly increased. His services in reconstructive surgery became greatly sought after. In 1594, he was even summoned to urgently travel to Vienna to treat the gunshot wounds of one of the wealthiest noblemen in the empire.

|

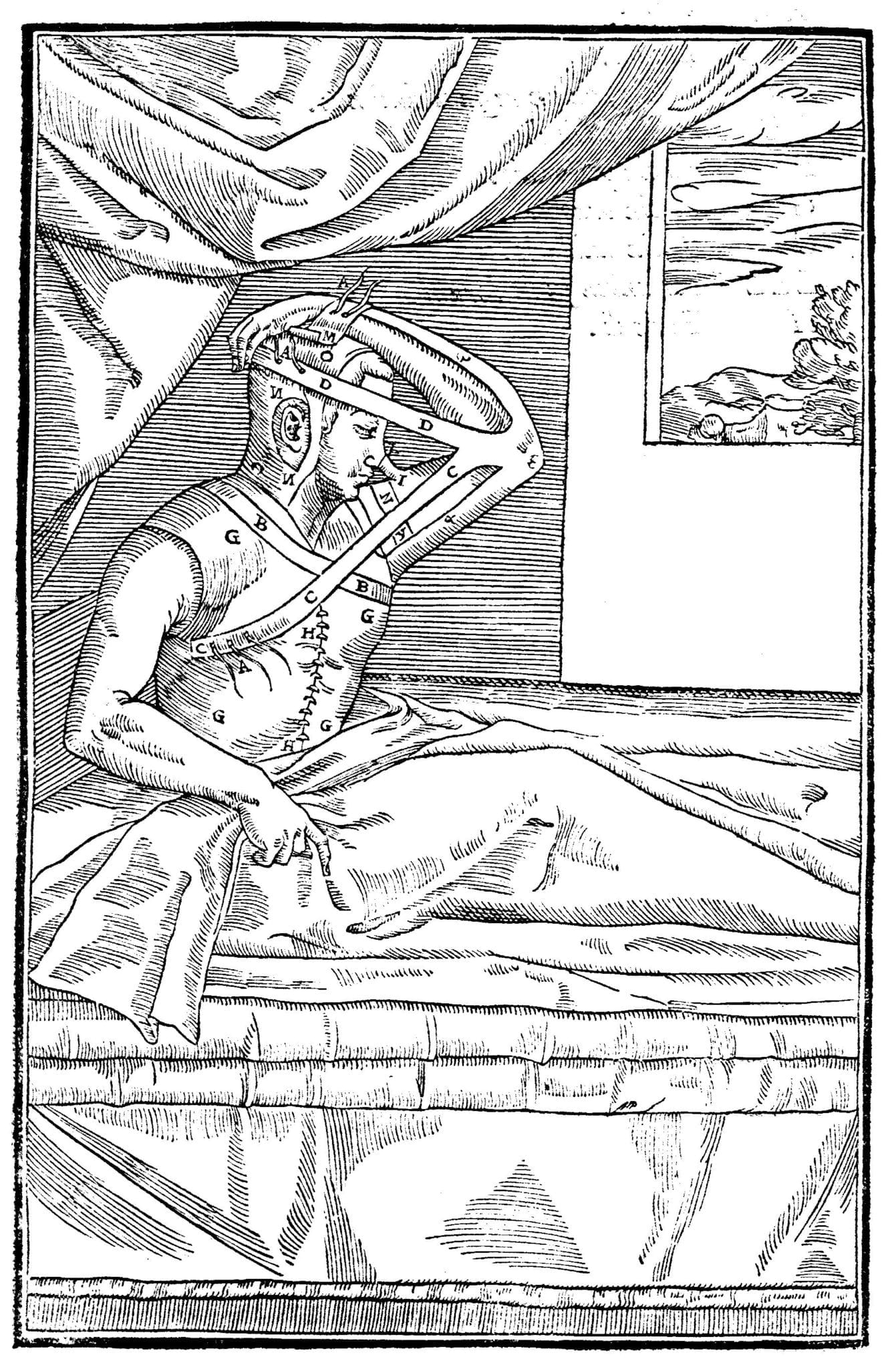

| From: Gaspare Tagliacozzi – De curtorum chirurgia per insitionem – Illustration n. 8. Via Wikimedia. |

The culmination of his career was the publication in Venice in 1590 of his famous two-volume book On the surgery of mutilations by grafting (De curtorum chirurgia per insitionem). In its forty-five chapters, it covered the anatomy of the face, the function of the nose, its importance in enhancing or spoiling the beauty of the face, the physiology of smell, the understanding that the nose does not itself smell but delivers the sensation to a higher center, also its role in supplying air necessary for speech and aid vocal resonance. There is a suggestion that certain kinds of noses are connected with certain personality types. The second volume describes the techniques of repairing injuries of the ear, lip, and nose.

Previous attempts at reconstructing the injured nose had largely failed because the implants taken from the upper arm included muscle as well as skin. But Tagliacozzi used only skin. He would raise a piece of skin from over the biceps, stitch one end of the face, immobilize the arm for at least three weeks, then cut off the connection between the flap and the arm, and mold the implant into the shape of the nose.

The book contains detailed instructions for the surgeon. He must have at least two assistants, prudent and diligent, quick in mind and nimble in body, but the responsibility rests entirely with him and cannot be delegated to assistants. The room must be carefully chosen, the lighting good, and the patient should lie in a proper bed on a pillow. Before surgery, the operative field must be washed with vinegar and an astringent drug applied to control the bleeding. Instruments must be chosen with care, the knives sharp and laid out in readiness for the surgeon. Bandages and swabs must be readily available. The tissues and the wound must be handled gently. After the procedure, the patient must first be kept on a sparse diet with little liquid and no wine. Instructions follow on how to handle complications such as inflammation, bleeding, or necrosis of the edges of the implant; how to wait some fourteen days before cutting the connection to the arm; how to apply the flap; and how to shape it so as to resemble a nose.

Some details and conclusions are characteristic of the times. Surgery is more likely to be successful if the patient’s temperament is well-balanced and less so if he is choleric, phlegmatic, or melancholic, in his childhood or old age. Spring is the best time to operate, winter the worst. Some noses are more difficult to repair than others, especially if parts of the bone are missing. Admittedly, a new nose will not look quite like the old, being softer and lighter in color. Hair may grow on it and may need to be shaved off. In time the nose should harden and exposure to the sun would give it a manly and attractive appearance. Theoretically, skin flaps could be taken from another person, but it would be difficult to keep two patients joined together for several weeks!

Despite the risks and inconvenience, many patients were willing to undergo the procedure rather than wear a silver nose or one fashioned from leather and attached to glasses or tied around the face. So Tagliacozzi’s fame spread widely and he was called in consultation to many princes and illustrious persons. He died in 1599, in Bologna, at the height of his fame.

After his death interest in rhinoplasty waned, in part due to moral and social objections, some arising from the church. Although most facial injuries were due to accidents, wars, and duels, a deformed nose also carried connotations of criminality and loose living. Criminals in Byzantine times were punished by having their nose slit; and during the Renaissance deformities of the nose were commonly due to syphilis. There were also some vague sexual connotations, the size of the nose held to indicate the size of the sexual organs, lasciviousness, or prostitution. Perhaps for some of these reasons, or for declining surgical skills in the seventeenth century, nasal reconstruction became less widely used. It did, however, undergo a renaissance after 1800. In our times it has become a flourishing specialty whose members correct congenital malformations, treat the victims of accidents, and cater to the vanity of men and women. It is a specialty that deservedly recognizes as its founder the sixteenth-century surgeon from Bologna, Gaspare Tagliacozzi.

Further reading

- Savoia P. Skills, knowledge, and status: The career of an early modern Italian surgeon. Bull Hist Med 2019; 93:1 (Spring).

- Gnudi MT and Webster JP. The life and times of Gaspare Tagliacozzi. New York, Herbert Reichner,1950.

- Santoni-Rugiu P, Mazzola R. Leonardo Ferranti (1517-1588): a barber-surgeon who influenced the development of reconstructive surgery. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery 1997;1997:570 (February)

- Webster JP. Gaspare Tagliacozzi; Plastic surgeon. JAMA 1969;207:1343:(7)

- Tomba P, Viganò A, Ruggieri P, Gasbarrini A. Gaspare Tagliacozzi, pioneer of plastic surgery and the spread of his technique throughout Europe in “De Curtorum Chirurgia per Insitionem”. European Review for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences 2014;18:450.

- Cock, E. Leading ‘em by the nose into publick shame and derision: Gaspare Tagliacozzi, Alexander Read, and the lost history of plastic surgery, 1600- 1800. Social History of Medicine 2015;28:1-21. (Feb)

- Menard S. An unknown portrait of the Tagliacozzi (1545-15990), the founder of plastic surgery. Plastic and reconstructive surgery 2019;7:issue 1.

GEORGE DUNEA, MD, Editor-in-Chief

Spring 2020 | Sections | Surgery

Leave a Reply