Rachel Bright

Kevin Qosja

Liam Butchart

Stony Brook, New York, United States

|

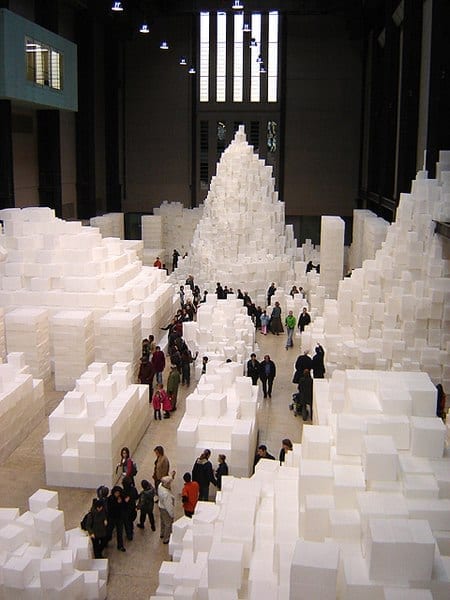

| Embankment by Rachel Whiteread. Turbine Hall, The Tate Modern, Bankside, London. 12 November 2005. Photo by Fin Fahey. In part inspired by the aftermath of her mother’s death, the white boxes are reminiscent of the many boxes the artist had to pack and unpack during that time. CC BY-SA 2.5. Wikimedia |

Art not only imitates nature, but completes its deficiencies. – Aristotle, Physics

A common complaint about medical students, doctors, and healthcare providers is that the scientific and technological progress of the last few decades has led them to neglect meaningful interactions, leaving patients bereft of the human touch—with dramatic consequences.1, 2 There is a tendency to assume that this is a modern complaint, but this betrays a myopic view of history. In 1927, Francis Peabody wrote “The Care of the Patient.” One of its more famous quotations is:

The most common criticism made at present by older practitioners is that young graduates have been taught a great deal about the mechanism of disease, but very little about the practice of medicine – or, to put it more bluntly, they are too “scientific” and do not know how to take care of patients.3

The consonance of Peabody’s arguments to contemporary discourse has not been lost on commenters.4 His article is not simply a critique; it also provides a standard by which to define the physicians who provide excellent care.

Pursuant to Peabody’s criteria, we propose to clarify how an exemplary physician should act using a humanistic approach. So, in accordance with Aristotle’s concept of mimesis—that truisms in life may be found in art—we suggest examining a physician from the literary pantheon.5 Who better to evaluate than Dr. Peabody (as he will be referred to for the remainder of our analysis)—not Francis Peabody, but Lucius Peabody, a character in William Faulkner’s Yoknapatawpha County. Beyond the cheekiness of the shared surnames, Dr. Peabody is widely considered to be an ideal humanistic figure.6 For example, Fargnoli and Golay write, “Dr. Peabody has long since stopped keeping accounts and charging fees, and cheerfully accepts a meal of corn pone and coffee or a measure of corn for his services . . . he filled a room with his ‘bluff and homely humanity.’”7 Dr. Peabody appears in several of Faulkner’s works, but we will consider him as depicted in As I Lay Dying (1930); this text offers not only third person accounts of his actions, but his narration of two chapters also offers critical insight into his thoughts and beliefs.

In order to survey these criteria, though, we must first identify them. In his essay, Francis Peabody acknowledges the complex interplay between body, mind, and society that often needs to be addressed to arrive at an accurate diagnosis and provide optimal care. He states:

What is spoken of as a “clinical picture” is not just a photograph of a man sick in bed; it is an impressionistic painting of the patient surrounded by his home, his work, his friends, his joys, sorrows, hopes and fears.8

Peabody is constructing a holistic conception of the patient, presaging Engel’s development of the biopsychosocial model by several decades, leaping past mechanistic accounts of disease.9 However, the physician must not simply collect biopsychosocial information; he must act on it. To Peabody, empathy and patient education are among the traits that the ideal doctor should display, fulfilling the expectation that “he dispenses sympathy, encouragement or discipline.”10 The physician must also possess intuition, both technically and humanistically. Peabody stated that though doctors are expected to be absorbed with combatting physical illness during critical moments, after those points, their attention must be refocused onto the patient as a person.11 Lastly, Peabody emphasizes the importance of quality of life, writing that “Death is not the worst thing in the world, and to help a man to a happy and useful career may be more of a service than the saving of life.”12

Our fictional Dr. Peabody begins to show how he embraces these criteria in his first narrated chapter. As he arrives at the Bundren homestead, he thinks:

When we enter [Addie] turns her head and looks at us. She has been dead these ten days. I suppose it’s having been a part of Anse for so long that she cannot even make that change, if change it be. I can remember how when I was young I believed death to be a phenomenon of the body; now I know it to be merely a function of the mind—and that of the minds of the ones who suffer the bereavement.13

Dr. Peabody explicitly focuses on the social determinants of Addie’s condition, specifically the connection between Addie’s prolonged death and her relationship to Anse. Anse’s symbology is one of decay (consider his rotted teeth, fallow farm, and decrepit body habitus); Dr. Peabody senses this—Addie will both die and decay because of her family, particularly her husband.14

Dr. Peabody’s trek to attend to Addie Bundren also illustrates his humanism and empathy. Though aware of his age and physical limitations, he still goes to the Bundrens’ house despite the storm and does not falter when the obstacle of “being hauled up and down a damn mountain on a rope” to get to Addie arises.15 His compassion for the family is further emphasized by his role as a pallbearer for Addie, an obligation that would not normally be his.16 Furthermore, while Dr. Peabody comments to Anse that he had recorded the visit in his ledger, he accepts only food from the Bundrens; financial recompense is not the motivation for his visit.17 By operating in-between altruistic care and entrepreneurialism, Dr. Peabody satisfies both the “heroic medicine” ethos of the time and the larger social impetus for empathy that undergirds the social contract between physician and patient.18

Addie’s final moments also illustrate Dr. Peabody’s intuition, honed over many years of practice. When he arrives at the Bundren farm and recognizes that the key window of treatment has passed, he focuses on Addie as a person. He carefully watches Addie’s eyes as she looks at the others in the room; he tries to speak to her amicably, he absorbs her overall state. Ultimately, he is able to appreciate Addie’s concerns, and he steps out.19 Dr. Peabody’s intuition makes him aware of the harm that Anse’s actions have had on Addie’s physiologic health, and though he does not yet understand the depth of this connection, he appreciates the powerful influences that social and familial connections can have on health, organic dysfunction, and psychological state.

When Dr. Peabody serves as narrator for the second time, towards the end of the novel, he forthrightly chastises Cash for having allowed Anse to encase his leg in cement—a clear moment of education, despite it coming too late for Cash.20 Though Dr. Peabody’s words are stern, they show concern for his patient. While he does eventually tell Cash that he will endure a limp for the rest of his days, he initially fixates on protecting Cash’s health from Anse’s carelessness.21,22 As Melnikoff argues, Dr. Peabody believes that what is most important is the patient’s ability to remain “naturally integrated into his or her social environment,” which Cash can do with a recovered leg but might not be able to do with Anse continually putting him in harm’s way.23 Aware now of the extent of Anse’s actions, Dr. Peabody asserts that it was “a damn good thing, too,” that Addie was approaching death, rather than living in suffering.24

Of course, Dr. Peabody is not perfect. He could have helped Dewey Dell with her pregnancy, if only he had known; he is a creature of his epoch, with views that today would seem classist or bigoted; and his technical facility has declined over time.25, 26 He is flawed, and yet he is altruistic and lives out the human aspect of the physician-patient relationship, fraught with genuine care and frustration.27 He illustrates the ideal doctor-patient relationship that Francis Peabody developed, at times exceeding it by exhibiting patience, altruism, and sacrifice, but his imperfections mark him as human, too.28 He not only imitates life as a literary character but completes it, giving Francis Peabody’s exhortations greater impact to those who read Faulkner’s work. Dr. Peabody trained when the patient came first and the technique of medicine second, espousing a naturalism that has been lost over time.29, 30 Perhaps what we can take away from this study, in the end, is that contemporary doctors should supplement their scientific proficiency with the humanistic care of previous eras, to be more like both of the Dr. Peabodys.

References

- Kelley, John M, Gordon Kraft-Todd, Lidia Schapira, Joe Kossowsky, and Helen Riess. “The influence of the patient-clinician relationship on healthcare outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials.” PloS One 9, no. 4 (2014): 1-7.

- Horton, Mary E Kollmer. “The orphan child: humanities in modern medical education.” Philosophy, Ethics, and Humanities in Medicine 14, no. 1 (2019). DOI: 10.1186/s13010-018-0067-y

- Peabody, Francis W. “The Care of the Patient.” JAMA 88, no. 12 (1927): 877-882.

- Dunea, George. “Francis Peabody: caring for the patient.” Hektoen International, Spring 2014. https://hekint.org/2017/02/01/francis-peabody-caring-for-the-patient/.

- Aristotle. Physics, ii, 8, quoted in Sandys, John Edwin. A History of Classical Scholarship: From the Sixth Century B.C. to the End of the Middle Ages: Volume 1. Cambridge: Cambridge UP (1903): 72.

- Melnikoff, Kirk. “‘carvin’ white folks’: Faulkner, Southern Medicine, and ‘Flags in the Dust.’” Mosaic 33, no. 4 (2000):145-162.

- Fargnoli, A. Nicholas, and Michael Golay. Critical Companion to William Faulkner. Infobase (2009): 263.

- Peabody, “The Care of the Patient,” 878.

- Engel, George L. “The need for a new medical model: a challenge for biomedicine.” Science 196, no. 4286 (1977): 129-136.

- Peabody, “The Care of the Patient,” 878.

- Peabody, “The Care of the Patient,” 882.

- Peabody, “The Care of the Patient,” 879.

- Faulkner, William. As I Lay Dying: The Corrected Text. New York: Vintage (1990): 43-44.

- Faulkner, As I Lay Dying, 52.

- Faulkner, As I Lay Dying, 43.

- Faulkner, As I Lay Dying, 79.

- Faulkner, As I Lay Dying, 43-44, 50-51.

- Melnikoff, “Southern Medicine,” 157.

- Faulkner, As I Lay Dying, 44-46.

- Faulkner, As I Lay Dying, 239-240.

- Melnikoff, “Southern Medicine,” 158.

- Faulkner, As I Lay Dying, 240.

- Melnikoff, “Southern Medicine,” 158.

- Faulkner, As I Lay Dying, 45.

- Bennett, Ken. “Faulkner’s As I Lay Dying.” The Explicator 47, no. 3 (1989): 42-43.

- Melnikoff, “Southern Medicine,” 158-159.

- Mathews, Laura. “Shaping the Life of Man: Darl Bundren as Supplementary Narrator in ‘As I Lay Dying.’” The Journal of Narrative Technique 16, no. 3 (1986): 231-232.

- Hurst, J Willis. “Dr. Francis W. Peabody, We Need You.” Texas Heart Institute Journal 38, no. 4 (2011): 327.

- Simon, John K. “The Scene and Imagery of Metamorphosis in ‘As I Lay Dying.’” Criticism 7, no. 1 (1965): 4.

- Faulkner, As I Lay Dying, 45

RACHEL BRIGHT earned her BS in Cell & Molecular Biology at Binghamton University and is now a second-year medical student at the Renaissance School of Medicine at Stony Brook University. Her interests include creative literature and hiking.

KEVIN QOSJA earned a BA in Biochemistry from Case Western Reserve University and is now a second-year medical student at the Renaissance School of Medicine at Stony Brook University. His interests include media and art analysis.

LIAM BUTCHART is a second-year medical student at the Renaissance School of Medicine at Stony Brook University. There, he is an MD/MA candidate, pursuing a master’s degree in Medical Humanities, Compassionate Care, and Bioethics in addition to his medical degree. His research interests include psychoanalysis and mental health, literary theory and analysis, and medical education.

Spring 2020 | Sections | Literary Essays

Leave a Reply