Stephen Martin

Durham, United Kingdom

|

| Fig. 1. Mrs. Jane Wilkinson, one of the first independent Georgian music teachers. English, Philip Gaugain, 1835. UK private collection. |

The Enlightenment was a philosophical movement in eighteenth-century Europe that had a major influence on the arts, science, education, religion, and politics. Its principles paved the way for women to work in professions (fig 1), advanced freedom and equality, and promoted racial and religious tolerance. Enlightenment ideas centered on ways of thinking and behaving as a force for progress in self and society (fig 2). These tenets remain relevant and important today.

Little has been written about the possibility for any philosophy or movement, even one as pervasive and long-lasting as the Enlightenment, to cause functional or even lasting physical changes in the brain. Learning and environment can mold brain size and function in particular task-related areas in a process known as neuroplasticity. This neural molding is driven by mechanisms that respond to brain activity, such as nerve growth factor proteins that enlarge neural networks, or neurotransmitters that increase blood flow and yield more glucose to active areas of the brain.

Breaking down the Enlightenment into mental functions—choosing a fair method

The Enlightenment emphasized clear and shared thinking, such as in Kant’s rationality, Diderot’s encyclopedic learning, and Goethe’s shared thinking. Hume extolled freedom from superstition. These specific mental functions interplay with emotions in both ill and healthy minds, emphasizing the brain’s complex, active circuitry and wide molding influences.

Clear and shared thinking

Sharing knowledge, learning, and clear thinking are all parts of rationality. Spatial learning has been shown in many studies to enlarge the hippocampus, an area of the brain involved in thinking and memory. Thinking about hard dilemmas exercises the brain’s prefrontal cortex, areas in the lower parietal lobes, and the cingulum.1 In ballet dancers, larger areas of brain gray matter were found not only the hippocampus, but also the cingulum, which regulates emotional tone.2 Did these kinds of interactions between rational, intellectual, and emotional activity also affect brain processes during the Enlightenment?

|

| Fig. 2. Joseph Banks, 1764, inheriting property deeds, now able to fund expeditions, full of rational optimism to learn. English, unsigned. UK private collection. |

Goethe wrote about the positive benefit of sharing rationality in his second novel, Wilhelm Meisters Lehrjahre,3 written over a twenty-five-year period and spanning the height of the Enlightenment:

“The world is so empty if one thinks only of mountains, rivers and cities; but to know someone here and there who thinks and feels with us, and though distant, is close to us in spirit — this makes the earth for us an inhabited garden.”

This description of thinking with added personal connection is now one of the four areas of modern Interpersonal Psychotherapy (IPT). Tackling “interpersonal deficit” can lift clinical depression. Goethe’s ideas are also similar to attachment theory, which has a wide modern application. Other proven antidepressant benefits of IPT, which address disputes and transitions, often draw heavily on rationality, particularly in planning new actions with relaxed, considered choice to reduce stress.

Rationality with correct thinking and action are well-established strands of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT). Fresh reasoning is the basis of restructuring depressed ideas, which again echoes Enlightenment ideals. Functional brain imaging studies of CBT show results similar to IPT in affecting mood circuits, further substantiating the potential for brain changes with interpersonal, interactive therapies.

Borderline personality states, in which rationality is suppressed, show reduced glucose use in the prefrontal cortex, a crucial area for healthy rationality circuits.4 This condition can respond to an interactive psychotherapeutic approach. There is, therefore, a brain rationality center and we know it changes with psychotherapy. If this occurs in disturbed patients, might Enlightenment ideals work similarly, enhancing rationality in people who are well?

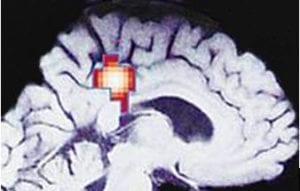

|

| Fig. 3. Activation of the posterior cingulum, integrating thinking and emotional tone, with Interpersonal Psychotherapy treatment for depression. |

Freedom from superstition

The human mind operates on a spectrum: from trust, to rational distrust, to a sense of being persecuted, to unshakable, false, persecutory delusional ideas. Superstition has been researched as a state of trust versus distrust in healthy individuals, and as a paranoid state in ill subjects. In testing reactions to various levels of honesty in sellers, the anger system was activated in the amygdala and orbitofrontal cortex with the least trustworthy sellers.5 With the most trustworthy sellers there was contentment circuit activation in the nerves around the cingulum. This is good evidence, in a carefully-designed study, that substantial functional change occurs in the brain with different levels of suspicion. The Enlightenment ideal of avoiding superstition may have similarly pushed mental activity away from anger circuitry and into contentment function.

IPT for patients ill with depression,6 even without medication, causes the area of the brain known as the cingulum or cingulate gyrus to activate as patients recover. Developing from the primitive limbic system for memory and emotion, it is far more advanced in humans in size and complexity. The front is responsible for regulating emotional tone. When damaged or not functioning properly, it can cause depression, anger, anxiety, and irrational obsessions. The back of the cingulum knits together thinking and emotional tone. With IPT there is an increase in activity, even without medication, as a patient progresses from a state of clinical depression to recovery: (fig 3) the cingulum is activated as contentment grows, as rationality increases, and as anxiety and suspicion diminishes. Adding this type of psychotherapy to antidepressants in severely depressed individuals7 also altered nerve dopamine receptors more than medication alone, with associated clinical improvement.

|

| Fig 4. Dr. Ferdinand Dejean, with emblems of learning, including Asia, Anatomia Reformata and a Mozart manuscript. Jacobus Buys, Dutch, c.1780. Baan Dong Bang Museum, Thailand. |

We can reasonably regard outward looking, relaxed kindness as opposite to the inward looking, restricted, fearful superstition which the Enlightenment tried to dispel. Adding together studies totalling 527 people in meditation,8 reliably separate patterns of brain activation and deactivation were seen across the studies for four common styles of meditation. Not all aspects of meditation related to significant brain changes, but kindness meditation did. There is other evidence of compassion in psychotherapy altering the activity of the cingulum.9

Rational inferences

It is striking that the two main psychotherapies for depression have shown major changes in brain function, and in areas connected to Enlightenment mental processes. Several connected brain regions may subtend Enlightenment philosophy, including those that regulate emotional tone (cingulum), memory/learning (hippocampus), and rationality (prefrontal). Given that functional brain change happens with talk therapy in patients with mental illness, then the effects of the Enlightenment’s positive behaviors in well individuals, whose minds ought to shift even more easily, would seem plausible.

Dr. Ferdinand Dejean (fig 4) had recognized that scarred brains were associated with dementia while doing post mortems in eighteenth-century Batavia,10 but at that time there was no understanding that learning or behavior could change brain structure and function. Franz Gall’s phrenology was right about functional localization in principle. In challenging modern times, beneficial philosophy has the potential to save and improve lives through learning, judgment, and morality, and deserves more research.

References

- Greene J D; Nystrom L E; Engell A D et al. (2004). “The neural bases of cognitive conflict and control in moral judgment”. Neuron 2004. 44(2): 389–400.

- Dordevic M, Schrader R, Taubert M et al. Vestibulo-Hippocampal Function Is Enhanced and Brain Structure Altered in Professional Ballet Dancers. Front Integr Neurosci. 2018 Oct 18; 12: 50.

- Goethe, JW v. Wilhelm Meisters Lehrjahre. Goethes Sämmtliche Werke, vol. 7, Stuttgart: J. G. Cotta, 1874, p. 520. First published 1795 – 1796.

- De la Fuente JM, Goldman S, Stanus E, et al. Brain glucose metabolism in borderline personality disorder. J Psychiatr Res 1997; 31: 531-41.

- Dimoka A. What Does the Brain Tell Us About Trust and Distrust? Evidence from a Functional Neuroimaging Study. MIS Quarterly. June 2010 34(2): 373-396

- Martin SD, Rai SS, Richardson R, et al. Brain blood flow changes in depressed patients treated with Interpersonal Psychotherapy or Venlafaxine Hydrochloride: preliminary findings. Archives of General Psychiatry 58, July 2001, 641-648.

- Martin SD. IBZM and HMPAO Studies in Interpersonal Psychotherapy for Depression. Proceedings of Association of European Psychiatrists, Heidelberg, Germany, May 2003. Reviews several studies.

- Fox KC, Dixon ML, Nijeboer, G M, et al. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2016 Jun; 65: 208-28. Functional neuroanatomy of meditation: A review and meta-analysis of 78 functional neuroimaging investigations.

- Kim JJ, Cunnington R, Kirby JN. The neurophysiological basis of compassion: An fMRI meta-analysis of compassion and its related neural processes. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2020 Jan; 108: 112-123.

- Allgemeine Literatur-Zeitung. Jena, 1793 Sept 3. This journal published Dejean’s findings to a general readership. Its reviewers included Goethe and von Humboldt.

Image Credit

- Figs 1, 2 & 4 © courtesy BDBMEC, under educational permission. All usable without charge, for non-commercial purposes.

- Fig 3. Image of posterior cingulum activation from Fig 3 in Martin et al, 2001, op cit., reproduced here with JAMA copyright permission.

STEPHEN MARTIN, MBBS, MRCPsych, LTCL (flute), is a retired UK neuropsychiatrist, Fellow of the Royal Asiatic Society, and honorary professor of psychiatry at Chiang Mai University Medical School, Thailand.

Profuse thanks to the Oxford philosopher Dr. Michael J Inwood, who unhesitatingly advised on and supported my reliance on his summary of the principles of the Enlightenment in The Oxford Companion to Philosophy. Likewise, to Dr. Sanjay Patel, Ed Martin, and Surgeon Lt Commander (retd) Duncan Veasey FRCPsych for their comments. PubMed and PsycINFO searches for the most relevant papers were carried out in March and April 2020.

Spring 2020 | Sections | Psychiatry & Psychology

Leave a Reply