Mariella Scerri

Mellieha, Malta

|

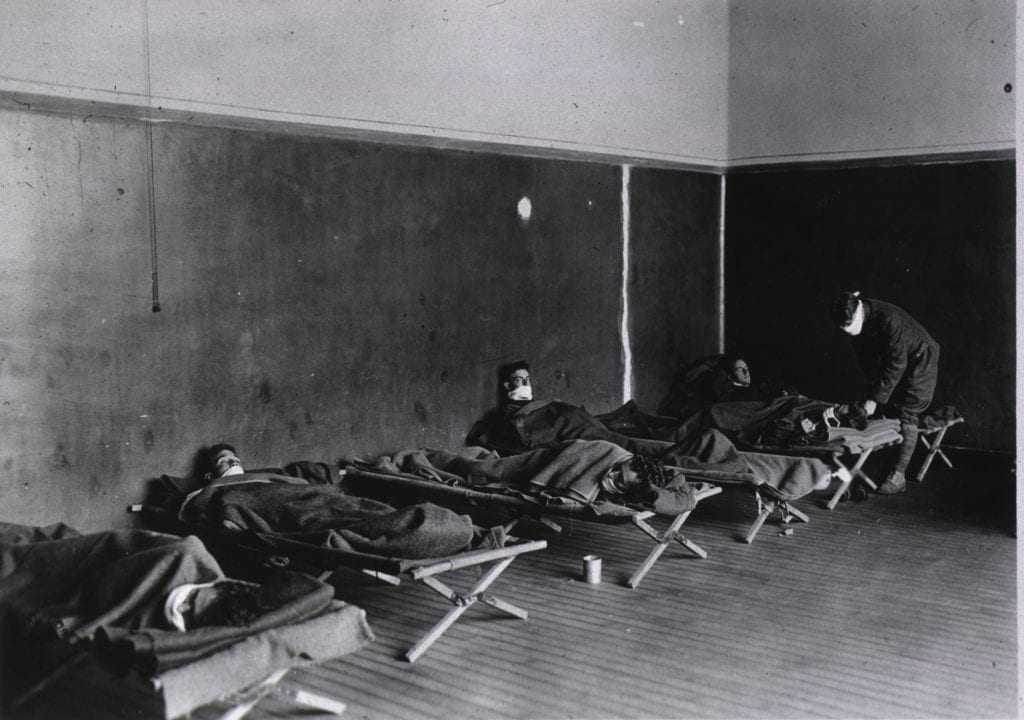

| U.S. Army Field Hospital No. 29, Hollerich, Luxembourg Interior view- Influenza ward. Copyright Statement: The National Library of Medicine believes this item to be in the public domain. |

Stalin’s claim that a “single death is a tragedy; a million deaths is a statistic”1 reverberates at a time when the world is gripped by fear as it tries to come to terms with a pandemic caused by the latest novel coronavirus, SARS-COV-2. Throughout history, humanity has had to contend with new diseases that spread like wildfire and leave scores of dead. A profound cultural and ethical aspect of all major epidemics is the loss of access to personal narratives. The collective replaces the individual as protagonist, and the “health of the public takes precedence over that of the individual, producing a reductionism that elides the particular and the subjective.”2 The hundred million deaths caused by the 1918-1919 influenza cannot be recounted as a meaningful story. They can only be reduced to statistics and trusted to speak for themselves.

For decades the 1918 virus was lost to history, a relic of a time when the understanding of infectious pathogens and the tools to study them were still in their infancy. Generations of scientists and public health experts were left with only the epidemiological evidence of the lethality of the virus and its deleterious impact on global population. A small ocean side village in Alaska called Brevig Mission was testament to this deadly legacy and crucial to the eventual discovery of the virus.3 In the fall of 1918, around eighty adults lived there; mostly Inuit natives. While different narratives exist as to how the 1918 virus came to reach the small village—whether by traders who travelled via dog-pulled sleds or even a local mail delivery person—its impact on the village’s population is well documented. During a five-day period in mid-November 1918, influenza claimed the lives of seventy-two inhabitants. Later, at the order of the local government, a mass gravesite marked only by small white crosses was created on a hill beside the village—a grim monument to a community all but erased from existence.4

Perhaps the differences between disease and war provide reasons for the inadequate attention to the 1918 influenza at a time when we might still have elicited its stories directly. The non-human perpetrators of disease escape us, and what remains is immense loss, loss in itself, the “real” without plot. The First World War gave the West a lesson in the bleak reality of human cruelty and destruction. The pandemic caused more physical damage but seemed to “convey no meaning at all, as it was overshadowed by the story of war, with its enemies, its weapons of mass destructions, its battles and its jubilant armistice.”5 The flu was less remarkable than war at a time when infectious disease was a daily fact of life. Before worldwide mass media, the global scale of the pandemic would not have been immediately available to local experience. Moreover, this disease was, after all, just the flu.

Narrative is a medium that carries and communicates the lessons of past suffering. Without narration, the past becomes abstract, and deceptively simple. Without the subjective embodiment of fact that produces meaning, narration falters. When multitudes of subjects are affected at once by painful events that disrupt secure frameworks of normality, subjective specificity is hard to find. The silence that surrounds the 1918 pandemic may not have been due only to the normal erasure of selective memory, but “there may also have been a refusal or inability to describe a trauma that might still have haunted its survivors.”6 Perhaps the flu overwhelmed language in ways that war did not.

One way to tell the story of the 1918 pandemic is through facts and figures, a collection of data whose impact is numbing and whose magnitude is almost inconceivable. However the raw numbers cannot convey the scenes of horror and misery that swept the world in 1918; scenes which became part of everyday life in every nation, in the largest cities and remotest hamlets. In this bleak scenario, personal narratives bear an important function. Stories convey how it was, or might have been, and what it meant to those who experienced suffering. The purpose of testimony is to instill in its witnesses the “ethical capacity to feel the pain of others.”7 This goal, shared by narrative medicine, “is to combat indifference—which is a kind of forgetfulness, a kind of silence.”8 Victor C. Vaughan, a medical doctor during the 1918 pandemic, describes one vivid “memory picture” from late 1918, one scene in a brief catalogue in his memoirs of the “grewsome” from a lifetime of medical experience:8

The faces soon wear a bluish cast; a distressing cough brings up blood-stained sputum. In the morning the dead bodies are stacked about the morgue like cord wood. This picture was painted on my memory cells at the division hospital, Camp Devens, in 1918, when the deadly influenza demonstrated the inferiority of human inventions in the destruction of human life.9

However, Vaughan does not recount the specificity of the epidemic. He simply says:

I am not going into the history of the influenza epidemic. It encircled the world, visited the remotest corners, taking toll of the most robust, sparing neither soldier nor civilian, and flaunting its red flag in the face of science.10

Mullen observes that “a world of silence surrounding survivors’ memories of the 1918 flu, is quickly leading to the very erasure of these memories.”11 Few references to the 1918 pandemic exist in literature, popular culture, or even in history books. This makes Katherine Porter’s story Pale Horse, Pale Rider, based on her personal experience as an influenza survivor, the most significant American literary work set during the pandemic.12 In the story Miranda, a reporter for a newspaper, enjoys a whirlwind romance with Adam Barclay, a young army officer, until she collapses from the virus. Katherine Anne Porter herself survived influenza as the epidemic reached its peak in Denver. When Porter fell ill, she had been seeing a young soldier named Lieutenant Alexander Barclay. While she was hospitalized, he contracted influenza and died.13 Pale Horse, Pale Rider thus testifies to Porter’s own personal trauma narrative. A great deal of time elapsed before she wrote her fictionalized narrative of the experience. After she recovered, she returned to work, focused on her writing, and made no mention of her illness until she moved to Switzerland in 1932. Her silence about the pandemic up to that point suggests that she tried, either consciously or unconsciously, to repress the memory. The Swiss Alpine landscape inspired her to revisit her memories as she wrote the story.

Porter based many of her fictional works on her personal experience, but Pale Horse, Pale Rider is her most autobiographical work.14 In a 1963 interview, she explained how the pandemic affected her:

It simply divided my life, cut across it like that. So that everything before that was just getting ready, and after that I was in some strange way altered, really. It took me a long time to go out and live in the world again. I was really “alienated,” in the pure sense. It was, I think, the fact that I really had participated in death, that I knew what death was, and had almost experienced it. I had what the Christians call the “beatific vision,” and the Greeks called the “happy day,” the happy vision just before death. Now if you have had that, and survived it, come back from it, you are no longer like other people, and there’s no use deceiving yourself that you are.15

Porter’s experience marks only one among millions of survivors, but other than her story, few narratives record the pandemic, so the collective memory—the common experience that establishes and maintains identity within a group—appears to be missing. In Collective Memory and Cultural Identity, Jan Assman explains that shared memories are essential to the formation and preservation of social identity.16 The relative absence of pandemic memory suggests a double loss, both the loss of the victims themselves and the loss of survivors’ group identity. Without a collective memory to connect the survivors to one another, their experiences of the pandemic become isolated and individualized. Public displays of memory, however, were not adequate even for the largest case of natural death in human history.17 Therefore, the pandemic was not sanctified or commemorated. If the pandemic was to be remembered, it would happen in individualized cases, in personal stories and intimate memories shared among families. Narrative serves as the primary means of recovery, allowing survivors to recover their identity while allowing listeners to experience the trauma emphatically. This dynamic renders narratives, particularly Pale Horse, Pale Rider, extremely important as such narratives effectively communicate the pandemic’s trauma to the reader. It may also be the best available means to communicate a historical narrative. In a work of literature, unlike a historical text, the reader can partially share the traumatic experience.

What remains is the persistent question of why there is a dearth of literary texts about the pandemic. One might expect that the convergence of a war and a pandemic would lend itself toward literary representation, but this has not been the case. The answer to the question of absence may be that the virus was both horrendous and completely ordinary. It was an enormous collection of personal tragedies that collectively amounted to a global calamity. Perhaps, both because of its vast scale and its manifestation as a fairly ordinary illness, a pandemic challenges memory in ways that other traumatic experiences do not.

In the still uncertain grip of a new global COVID-19 pandemic, it matters now more than ever that we hold on to the stories told by Victor Vaughan and Katherine Porter. We live in a culture of memoirs and pathographies, of confession and testimony, truth and reconciliation. Comparisons concerning witnessing and remembering mass suffering might be of value. While the purpose of testimony is to instill in its witness the “ethical capacity to feel the pain of others,”18 numbers and statistics desensitize humanity. Perhaps narratives of the 1918 pandemic may help us combat indifference, an indifference which transforms itself in forgetfulness; a kind of silence.

Notes

- Joseph Stalin. “Washington Post 20 Jan, 1947” in Oxford Essential Quotations ed. by Susan Ratcliffe. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016).

- Catherine Belling. “Overwhelming the Medium: Fiction and the trauma of pandemic influenza in 1918”, Literature and Medicine 28 No 1 (2009): 55 – 81.

- Douglas Jordan. “The Deadliest Flu: The complete story of the discovery and reconstruction of the 1918 pandemic virus”, CDC: Centres for disease control and prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/pandemic-resources/reconstruction-1918-virus.html

- Jordan.

- Belling, 56.

- Belling, 57.

- M Clark. “Holocaust Video Testimony”, Oral History and Narrative Medicine, 24 No 2 (2005): 266-282, p. 267.

- Victor C. Vaughan. A Doctor’s Memories. (Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merill, 1926).

- Vaughan, 383-384.

- Vaughan, 383-384.

- Thomas Mullen. The Last Town on Earth. (New York: Random House, 2006), 329.

- Katherine Porter. Pale Horse, Pale Rider. (New York: The Modern Library, 1939).

- Joan Givner. Anne Porter: A Life. (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1982), 124-130.

- Givner, 124-130.

- Robert H. Brinkmeyer. “‘Endless Remembering”: The artistic vision of Katherine Anne Porter”, Mississippi Quarterly 40 (Winter 1986): 5-19.

- Jan Assman, “Collective Memory and Cultural Identity”, trans. by John Czaplicka, New German Critique 65 (Spring 1995): 125 -133.

- Assman, 125-133.

- Annette Wieviorka. “The Witness in History”, trans. by Jared Stark. Poetics Today 27 No 2 (2006): 385-397.

Bibliography

- Assman, Jan. 1995. “Collective Memory and Cultural Identity”, trans. by John Czaplicka, New German Critique 65 (Spring): 125 -133.

- Belling, Catherine. 2009. “Overwhelming the Medium: Fiction and the trauma of pandemic influenza in 1918”, Literature and Medicine 28 No 1: 55 – 81.

- Brinkmeyer, Robert H. 1986. “‘Endless Remembering”: The artistic vision of Katherine Anne Porter”, Mississippi Quarterly 40 (Winter): 5-19.

- Clark, M. 2005. “Holocaust Video Testimony”, Oral History and Narrative Medicine, 24 No 2: 266-282.

- Givner, Joan. 1982. Anne Porter: A Life. (New York: Simon & Schuster).

- Jordan, Douglas. “The Deadliest Flu: The complete story of the discovery and reconstruction of the 1918 pandemic virus”, CDC: Centres for disease control and prevention.

- Mullen, Thomas. 2006. The Last Town on Earth. (New York: Random House).

- Porter, Katherine. 1939. Pale Horse, Pale Rider. (New York: The Modern Library).

- Stalin, Joseph. 2016. “Washington Post 20 Jan, 1947” in Oxford Essential Quotations ed. by Susan Ratcliffe. (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

- Vaughan, Victor C. 1926. A Doctor’s Memories. (Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merill).

- Wieviorka, Annette. 2006. “The Witness in History”, trans. by Jared Stark. Poetics Today 27 No 2: 385-397.

MARIELLA SCERRI, B.Sc (Hons.) Nursing, B.A (Hons) English, PGCE (English), M.A English, is currently a teacher of English. She is a former staff nurse and worked in the cardiology department at Mater Dei Hospital, Malta before commencing her teaching post. She holds a Masters in English Language and is reading for a PhD in Medical Humanities at Leicester University. She is also a member of the HUMS programme at the University of Malta.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 12, Issue 3 – Summer 2020

Leave a Reply