Jayant Radhakrishnan

Darien, Illinois, United States

Sir Alexander Fleming had many talents. His discoveries of lysozyme in 1923 and in 1928 the antibiotic effect of the fungus Penicillium notatum are well known.1 Less well known is that he was a skilled marksman and a member of the London Scottish Regiment during World War I. There is a questionable story that the captain of his rifle club, not wanting Fleming to move away from the area for surgical training, persuaded him to switch from surgery to bacteriology so he could continue with the club.2 The least well known of his talents was the creation of a very unusual art form.

Fleming became a member of the Chelsea Arts Club on the recommendation of the painter James McNeil Whistler. Fleming’s regular art work was quite pedestrian but he had a special technique up his sleeve: using germs to create art. He would brush a handkerchief with pigmented bacteria. Initially the organisms were invisible, but after a period of incubation when colonies formed, vivid colors were revealed. He is reported to have used Serratia marcescens, which produces a red pigment at room temperature; Micrococcus roseus for pink, since it produces a carotenoid pigment; Bacillus subtilis for orange, Chromobacterium violaceum for purple, Micrococcus luteus for yellow, and Micrococcus varians for its white color.3

To use organisms in such a manner requires more than just a knowledge of the colors they form. They must first be incubated separately at the ideal temperature for that organism. B. subtilis grows best at 25-35°C, C. violaceum at 35-37°C, and E. coli at 37°C. One also has to pay attention to the special nutritional requirements of each organism. Next, to have all the colonies mature at the same time to create the artwork, they must be inoculated into the medium based on their rate of growth. Unless growth stops once the desired effect is attained, an organism would grow into the adjoining one and the colors would run together. On the other hand, if organisms run out of nutrients they will die. Today some artists preserve their artwork by sealing it with epoxy or acrylic once growth of the organism is complete. It is not known whether Fleming made any attempt to preserve his art or whether he preferred its inherently transient nature. He graduated from using a handkerchief to working with Petri dishes filled with agar, which he inoculated with a wire loop. He painted houses, ballerinas, mothers feeding children, stick figures fighting, and many other scenes.4

It is unclear how Fleming first decided to use organisms to create art, but his work became increasingly vibrant as he discovered more colorful bacteria. Unfortunately his artistic talent was not appreciated, not even by Queen Mary who is said to have rushed past an exhibit he created for her at St. Mary’s Hospital in which he made a Union Jack with bacteria!

Individual artists and groups such as the Canadian Petri Dish Picasso are expanding on Fleming’s tradition of painting with organisms. Interest in the technique was reborn after a beautiful work of a San Diego beach scene created by Nathan Shaner in the laboratory of the biochemist Roger Y. Tsien became popular. Tsien was awarded the Nobel Prize for Chemistry in 2008 for his discovery and development of Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP).5 Shaner created the beach scene using GFP.

The list of organisms used has also increased tremendously. Modern art works are made using different yeast species and protists in addition to bacteria. Some organisms are used as such while others are engineered to express fluorescent proteins. Radiation has also been used on the agar medium to control growth of organisms in certain parts of the art work. This technique has been named bacteriography.

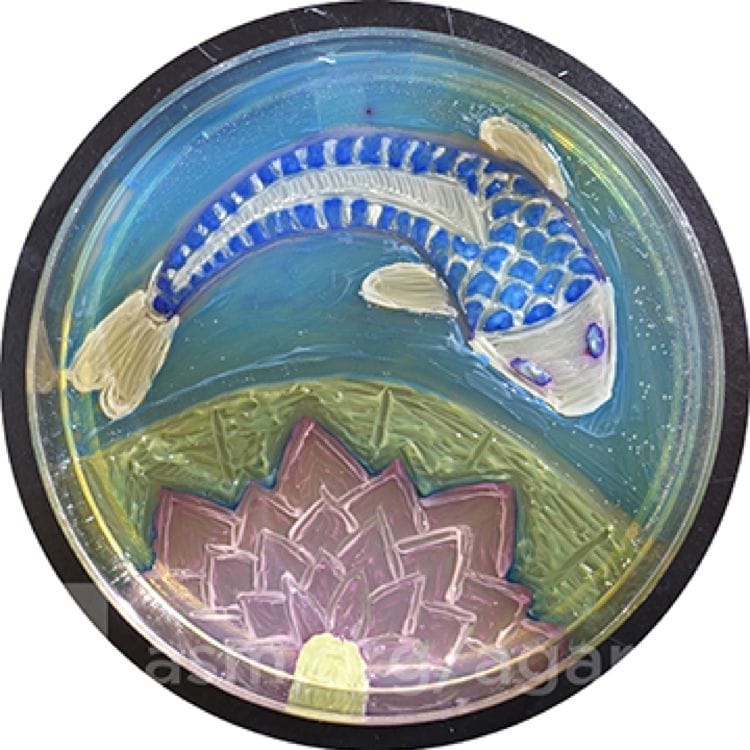

Since 2015 the American Society of Microbiology has conducted an annual Agar Art Contest. The winner of the 2019 contest was Arwa Hadid, an undergraduate student at Oakland University in Rochester Hills, Michigan who created a beautiful work titled “Seemingly Simple Elegance” in which she used nine organisms to make a koi fish and a lotus flower in water (Figure 1).

Fleming’s discovery of penicillin was initially ignored and rediscovered years later. Similarly, his discovery of a unique art form was not appreciated until many years later.

Endnote

- “On the plate is a simple portrait of a Koi fish with a lotus flower. However, hidden within the lines are nine different organisms used to bring the picture to life. The lotus flower is made of Micrococcus luteus as a starting point for the center of the flower. Radiating out of it are petals made of Escherichia coli outlined with Staphylococcus saprophyticus to add depth and color to each individual stroke. Surrounding it is a lotus leaf thick like the organism it is made of, Proteus vulgaris. The Koi, on the other hand, is made of Klebsiella pneumoniae, a mucoid and almost metallic organism, the color of which is enhanced with Staphylococcus aureus which outlines each individual scale and gives shape to the body. A subtle orange tinge was given to the fins with Proteus mirabilis while the eyes are a piercing metallic blue haloed with red that is created by Citrobacter freundii. To encompass it all in calm blue water is Enterococcus faecalis.”

References

- Fleming A (1929). On the antibacterial action of cultures of a penicillium. With special reference to their use in the isolation of B. Influenzæ. Brit J Experimental Pathol 10;226-236

- Alexander Fleming biography. Les Prix Nobel. The Nobel Foundation 1945. Techsciencenews.com. Sunday March 8, 2020.

- Alexander Fleming (2020) From Wikipedia the Free Encyclopedia.

- Dunn R (2010). Painting with penicillin: Alexander Fleming’s germ art. Smithsonianmag.com July 11, 2010.

- Roger Y. Tsien – Facts. NobelPrize.org. Nobel Media AB 2020. Mon. 16 Mar 2020. https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/chemistry/2008/tsien/facts/

JAYANT RADHAKRISHNAN, MB, BS, MS (Surg), FACS, FAAP. Following a Surgery Residency and Fellowship in Pediatric Surgery at the Cook County Hospital, Jayant completed a Pediatric Urology Fellowship at the Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston. He returned to the County Hospital and worked as an attending Pediatric Surgeon and served as the Chief of Pediatric Urology. Later he worked at the University of Illinois, Chicago from which he retired as Professor of Surgery & Urology, and the Chief of Pediatric Surgery & Pediatric Urology. He has been an Emeritus Professor of Surgery and Urology at the University of Illinois since 2000.