Annabelle Slingerland

Leon Lacquet

Leiden, the Netherlands

|

|

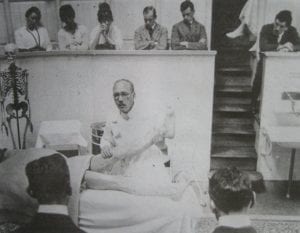

Ferndinand Sauerbruch at a medical lecture at the University of Zurich, between 1910 and 1917. Source unknown. Accessed via Wikimedia commons. Source |

Ferdinand Sauerbruch (1875-1951) was one of the most important thoracic surgeons of the first half of the twentieth century, remembered for pioneering a method that would allow access to the thoracic cavity and the heart. Three years after his death in 1954, his life was detailed in a movie authored by ghostwriter Hans Rudolf Berndorff (1895-1963) and titled Das war mein Leben, (This was my life). It was an example of how a young man starting life in an ordinary nonmedical family overcame obstacle after obstacle to achieve extraordinary heights of inventiveness and competence.

When Ferdinand was only two years old, his father, a manager of a fabric manufacturing company, died of tuberculosis. He had to move with his mother from Barmen (Wüppertal) to Elberfeld (near Erfurt), where his grandfather Hammerschmidt had a shop as an artisan shoemaker for wealthy ladies. In his early studies, Ferdinand was supported by the earnings of his grandfather, mother, and aunt, who early on recognized his talent. He attended the gymnasium, or secondary school, taking a year in natural sciences at the University of Marburg and then graduating from the medical school as a family physician. He was fired after taking a patient for an emergency surgery on Sunday, disturbing the religious service of the Protestant Deaconess hospital of Kassel and calling for help in the OR. He subsequently worked as a voluntary physician assistant in pathology and anatomy in the poor neighborhood of Moabit in Berlin.

Impressed with his scientific work, Professor Langerhans arranged for him to secure a voluntary position in surgery in Breslau, now Wroclaw in Poland. It was there that he worked under the German-named Polish surgeon Johann Freiherr von Mikulicz-Radecki. Perhaps stimulated by his father’s death from tuberculosis, he began to work on a method to open the thoracic cavity without the lungs collapsing, the so-called negative pressure chamber from which air was led outward to reach a pressure of -10 mmHg. His successful test on a dog who survived without his lungs collapsing led Dr. Eloesser, later a thoracic surgeon in San Francisco, to pronounce that he had just assisted at the birth of thoracic surgery, of which Ferdinand Sauerbruch should hence be seen as its father.

It later came about that the head surgeon Geheimrat Mikulicz, surprised by the rapid progress of his protégé’s research, visited on the day when air had entered the cylinder, the lungs collapsed, and the dog died. Sauerbruch, seen as a failure, tried to justify this failure and burst into expletives, leading to his being fired. He continued his work on his new invention in a private clinic in Breslau and made it a success. Through the son-in-law of Mikulicz, Dr. Willy Anschutz (1870-1954), he apologized for his language and was reinstated by Mikulicz. The first use of the negative pressure chamber on a human, performed by Mikulicz and assisted by Sauerbruch, was also a failure, but the chief Mikulicz took responsibility. Subsequent surgeries were successful and the results were published in the scientific literature. Mikulicz introduced Ferdinand Sauerbruch to the Berlin Surgical Congress and became his best friend. The two surgeons were appointed to develop this approach in the hospitals of Breslau, and Sauerbruch finished his thesis on negative pressure just before Mikulicz died in June 1905. Invited by the German-born surgeon Willy Meyer, he undertook an American tour that led to international recognition of his work. His boat voyage to the States was paid by his father-in-law, while in the States he was the guest of the American surgeons. In 1910, he was appointed professor of surgery in Zürich at the demand of the physicians of the Swiss sanatoria and he could finally build his own negative pressure chamber at the Cantonal Hospital of Zürich.

During World War I Sauerbruch served part-time as a health officer in the German army. With Aurel Stodola of the Technical University, he co-developed the “artificial hand” and secretly exchanged letters of Emperor Wilhelm II, with the King of Bulgaria, and the Sultan of Turkey. In Zürich he engaged in private practice on a site consisting of two villas and a connecting operating room as well as his private house with consultation facilities surrounded by land for his horses and animals. His practice thrived and he treated world leaders such as Lenin. He published Thoracic Surgery in 1937 and developed new surgical instruments. His wife, Frau Ada Scholz, the only child of the Professor of Pharmacology, covered the financial and administration part, and educated their three (out of four) surviving children. He befriended the Jewish families of Oppenheim and the famous portrait painter Liebermann. Zürich was clearly the high point of his happiness on all levels. It was no surprise that in 1975, on the 100th birthday of Sauerbruch, the Deutsche Bundes Post printed stamps with his picture, reviving the admiration of the nation for their exemplary hero. Earlier on he had received further great recognition, invited by King Ludwig III of Bavaria to become a professor at Münich, and was also invited abroad by surgeons such as Carel ten Horn, who had worked under him from 1919 to 1923 to perform procedures at the Sanatorium for Tuberculosis “Dekkerswald” near Nijmegen. His interest in orthopedics led him to edit a book with ten Horn on the “artificial hand.”

Sauerbruch also operated on Anton Graf Von Arco auf Valley, the murderer of Kurt Eisner, a Jewish revolutionary and pacifist who had started the November revolution for the new Republic. He treated Hitler for his shoulder after the putch, and became physician to Hindenburg, the second president of the new Weimar Republic, being present as Hitler visited Hindenburg when he was on the verge of dying in July 1934. He remained professor in Munich, and was chosen as successor of Professor Bier with the task of merging the professorial positions at the Humboldt University and the Clinic of the Charité in Berlin (1927, 1928). He subsequently had operating rooms built as bunkers underground and joined the Berliner Mittwochsgesellschaft, in which sixteen experts from different fields but with prestigious positions in society met every two weeks to discuss science at one of its members’ private homes.

Privately, he divorced Frau Ada, married the young pediatrician Margo Grozmann (1903-1955) in 1939, and moved from the idyllic Wannsee to Grünwald-Berlin. During the war, they were rescued from their bunker by some Russians whose family members he had operated on. They appointed him as head of the hygienic service in Berlin. Subsequently, the Allied forces fired him for suspicion of working with the Nazis. German physicians, as well as medical historians, wrote that during the war he had played a double role, supporting the Nazis but also treating the victims of the regime. In fact, he had refused to fire his Jewish colleagues such as his chief surgeon Rudolf Nissen, promoting his career so that in 1942 he operated on Einstein at the Jewish Hospital Maimonides in America. He also tried to stop experiments with typhus and the Euthanasia Program T4, received the honor of Hitler’s State Council from Göring (1934), and together with Bier won the German National Prize for Arts and Sciences from Hitler in Nuremberg, accepting 10,000 R.M. and a yearly bonus of 200,000-300,000 R.M. where Hitler had stopped Germans from receiving the Swedish Nobel Prizes. Under protest of the Gestapo, he attended the funeral of Liebermann (1935), but in 1942 he became General Physician Inspector of the German Military Health Services, a member of the Academy of Military Physicians which approved of experimenting on human beings in the camps. One example was on typhus by his former assistant Dr. Karl Gebhardt, physician to Himmler (Ravensbrück), and another on mustard gas by Natzweiler (Strassburg). In 1943, he received the Knight’s Cross of the War Merit Cross by the National Socialist Karl Brandt, an SS general and war criminal later hanged in Nuremberg. In the same year, he spoke in Brussels on Paracelsus of Theophrastus von Hohenheim (1493-1541), a controversial physician interested in theology, alchemy, astrology, and botanic toxicology, and natural healing, who was popular with the Third Reich and that with Himmler and Göring promoted natural healing and alternative medicine. At the denazification trial (1949) not all the facts were known and together with the good he did for the Jewish and victims of war, he was not convicted or found guilty.

He continued under Russian military support marching on for communism, however as his surgical skills were deteriorating, he had several deaths in the operating room and following a fight with a chief physician at the Charité was persuaded to resign from his professorial position in 1949 at age seventy-four. He continued in private practice in Berlin-Grünewald without anesthesia and in nonsterile circumstances, wrote the introduction to his biography with a quotation from Paracelsus, but then died from a stroke on July 2, 1951.

Soon after his death, his memoirs were published. They included the fascinating story of his early life and his medical advances, his fight against tuberculosis, his war experience, and how he was threatened by the communists but saved by the intervention of the son of a patient whom he had treated for free. It is mentioned that occasionally he would lose his temper when his assistants made foolish remarks and that there were times when this made him feared. The book was highly recommended, stating “his revolutionizing principles and significant contributions guided the development of modern cardiothoracic surgery. His inexhaustible flow of brilliant insights to tackle baffling medical obstacles, his devotion to patients and his dynamic personality led him to the heights of fame.” Left out in the book was his role in the Nazi government, the high mortality figures, his authoritative egocentric nature, extravagant lifestyle, alcoholism, and womanizing. But he remains one of the great pioneers in the history of surgery.

Today

The laboratory of experimental surgery in the cellar of the surgical clinic in Breslau still exists and can be visited. The museum exposing Liebermann’s work can be visited as well. It is the villa he lived in during the summer months at the Wannsee, near Berlin, damaged by WWII but restored in 2006.

Further reading

- Berry Frank B. Ferdinand Sauerbruch. JAMA; 1964:190, 946. Letter.

- Dewey M, Schagen U, Eckart WU., Schönenberger E. Ernst Ferdinand Sauerbruch and his ambiguous role in the period of National Socialism. Annals of Surgery: Aug 2006; 244(2): 315-321.

- Editors JAMA. Ferdinand Sauerbruch (1875-1951)-Thoracic Surgeon. JAMA; 1964:190 (2): 152-153. Editorial.

- Lacquet L.K.M.H.: Professor Dr. Ferdinand Sauerbruch. 1875-1951. Pionier en Vader van de Thoraxchirurgie (Ferdinand Sauerbruch, Pioneer and Father of Thoracic Surgery), presentation at the assembly of retired professors, the Netherlands, 16 June 2016.

- Sanjay M. Cherian SM, Nicks R, Lord RSA. Ernst Ferdinand Sauerbruch: rise and fall of the pioneer of thoracic surgery. World J Surg: 2001; 25: 1012–1020.

- Sauerbruch F. Das war mein Leben. Verlegt bei Kindler. München, 1951.

- Sauerbruch F.: A Surgeon’s Life. Translated by Fernand G. Renier and Anne Cliff. Andre Deutsch. World J. Surg. 25, 1012–1020, 2001.

- Thorwald J. Die Entlassung. Das Ende des Chirurgen Ferdinand Sauerbruch. 1960. (The Dismissal The incredible story of the last years of Ferdinand Sauerbruch. One of the great surgeons of our time by the author of the century of the surgery and the triumph of surgery).

- Thorwald J. Tod des Titanen Jurgen. Der Spiegel. 47/ 1960.

- Tietz Tabea. The Medical Breakthroughs of Ernst Ferdinand Sauerbruch. SciHi Blog, 3. July 2015, scihi.org/medical-breakthroughs-ernst-ferdinand-sauerbruch/.

ANNABELLE SLINGERLAND, MD, DSc, MPH, MScHSR, was asked while in Ndala, Tanzania to take up thoracic surgery at Leiden University, following which side tracked to monogenic diabetes. She is also working in medicine and history encompassing diabetes and cardiovascular disease with Oxford University/ UK, Joslin Diabetes Center, and with Harvard University/ MIT, Boston staff. In the latter she explores the history of bypass surgery in particularly the Holland Houston London and Geneva airlifts where the US filled in a capacity demand in the seventies. She swims and sails rivers and oceans for charity and includes medicine and history narrating on those encounters.

LEON K.M.H. LACQUET, MD (1933), is a retired Cardio- Thoracic surgeon who trained in his home country Belgium and extended his training in Leiden the Netherlands. His special interest and his reflection on the history of the hospitals he worked at were translated into presentations in the Netherlands. He was Professor and head of the department of Thoracic and Cardiac Surgery at the Catholic University of Nijmegen from 1970 to 1998, professor together with Pierre J.M. Kuijpers, who introduced the coronary artery bypass in Holland in 1968 after its introduction in the US. He was also Consultant Thoracic Surgery at the Sanatorium and Lung Clinic Dekkerswald in Groesbeek-Nijmegen.

Leave a Reply