F. Gonzalez-Crussi

Chicago, Illinois, United States

Figure 1. The Birth of Benjamin and the Death of Rachel, by Francesco Furini (1600 or 1603–1646). Wellcome Collection. Public domain.

Memory is to old age as presbyopia (far-sightedness) is to eyesight. Presbyopia makes you lose the ability to see clearly at a normal near working distance while maintaining a sharp distant vision. Just so the elderly recollect in painstaking detail what happened to them fifty or sixty years ago, yet have trouble remembering what they had for breakfast this morning. Curiously, both presbyopia and enhanced distant memory come with aging; it seems ordained that both the bodily and the mind’s eye must change simultaneously. This is why, in my late years, I remember quite clearly an event that happened long ago.

I see myself as a recently arrived immigrant working as an intern in a hospital in the Southwest of the United States. My alertness is impaired by protracted sleep deprivation; for these are the times when a medical internship is deemed a harsh ritual of initiation, a test of endurance. Interns are expected to withstand a brutal schedule of twenty-four-hour shifts thrice a week and to face every crisis─and every scornful browbeating─with imperturbable self-composure. Strange times! The system seems grounded on the uncharitable premise that the oppressed of today shall be the oppressors of tomorrow. Alas, each pang finds a lenitive in the unchristian thought that those who follow us shall suffer the same vexations, only this time at our own hands.

The negativism of my thoughts in those days is rooted in profound insecurity. I am acutely aware of my incomplete command of the English language and woeful lacunae in my knowledge and experience. I am assigned to a rotation in the obstetrics department, and a telephone call at 2:00 a.m. requests my presence in the delivery suite: a woman is in labor.

I recall my surprise when first looking at the patient. Marisela, by name: a poor, uneducated, Mexican-American young girl who had no prenatal care, and now is about to become an unwed mother in her abysmally dispossessed community. A prey to fear, she submissively complies with our every indication: “Put on this gown.” “Extend your arm, for an injection.” “Scoot over to this side of the bed.” She is utterly dependent here, therefore inferior and in the power of strangers who outrank her, dominate her, and order her around. But even in her meek submissiveness I detect a certain grace. Maupassant says of one of his female personages that “fate had made a mistake with her.” This applies to Marisela, for such is the patient’s name. Her adolescent, slender body is gracefully delicate; the skin, alabaster-white and translucent, allows the examiner to see bluish rivulets of veins. Her hands, in particular, are of a remarkable elegance. It is said that Murillo could find in Southern Spain, as models for his madonas, women who preserved much African blood in them, and with hands of an incomparable finesse.

My ability to communicate in Spanish helps to reduce the estrangement she must feel at this time. An equal may be perceived, in a way, as a duplicate of oneself; but a situation of inequality always sets into relief the idea of “the Other.” And the superior, the commander, the “boss” embodies otherness most acutely; for he or she is, as a thinker once remarked, “the most ‘other’ of all the ‘others.’” Perhaps my sharing her language contributes to attenuate the patient’s lacerating sense of alterity brought forth by the obvious inferiority of her current situation.

She had been alone throughout gestation. No young husband to smile at her affectionately and one might say “paternally,” with each reminder that soon a baby would be with them crying, feeding, smiling, and, in a word, living. And now that the great wave of childbirth is fast approaching, relentlessly growing bigger and threatening to engulf her and to drown her, still no one is by her side to tell her words of tenderness and comfort. This may be why the few nugatory exhortations I utter to calm her in the language of her childhood elicit each time a look of profound gratitude: Tranquila! No te preocupes. La Virgen nos ampara. Yes: may I be forgiven for having assured her that we counted with the assistance of the Holy Mother of God, whose miraculous intercession I had no power to invoke and certainly no entitlements to deserve.

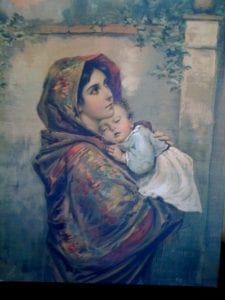

This is her first child. Utterly unprepared, she must engage in the millenarian struggle, the unremitting hand-to-hand combat reenacted each time along millions of years. Haggard, sweaty, disheveled, she tosses about and moans dolefully. It is a struggle: agon, said the Greeks, a word-root persisting in the term “agony.” It seems that as the new life ascends she is gradually lowered into the pit of death. This life-death juxtaposition of childbirth was starkly obvious in epochs of high maternal mortality, fortunately bygone. Artists rarely captured it with the dramatic intensity of Francesco Furini’s The Death of Rachel (Fig. 1), for childbirth has generally been a taboo in art.

Erasmus wrote that a traveler, intrigued by the agitation of people next to a house, asked what was happening, and was told that, right then, inside that house, a woman was being cut in two. “Heavens!” exclaimed the traveler, “What did she do to deserve such an atrocious punishment?” A wag explained that the woman was giving birth to a child. Indeed, childbirth is a scission, a harrowing separation. It is not purely a play on words to say that a woman is broken into two: a part of her—”blood of her blood and flesh of her flesh”—is being severed from her body.

Nonetheless, childbirth is usually hailed with unalloyed exhilaration. We wish to believe that the newly born have come to build a worthier world upon the ashes of their parents. Only this time the occasion is far from celebratory. Marisela delivers a premature infant that has difficulty breathing. How clearly do I see, with my mind’s eye, this piteous, frail little creature! Tottering between life and death, exhausted, limp, still covered by the sebum proper to the fetal skin, red with maternal blood and soiled with meconium, as infantile excrement is called. At this time, a premature infant with respiratory distress has few chances of survival. I feel it was wrong for him to leave the maternal enclosure. Why quit the warm, protective enclave for a world “choked with hate,” as Keats put it,1 where “every face scowls, and every windy quarter howls”? The whole situation makes me wonder that the ancient dictum, Optimum non nasci, “the best of is not to be born” is more than a rhetorical topos. Because death, the Supreme Negator, says “No!” to life, but also to its miseries; No to our continuation, but also to our malice; and No to the future, but also to hate, beastliness, and inhumanity.

As soon as she felt her son’s warm, damp arm contacting the medial surface of her thigh, the infant was taken away to the neonatal unit for specialized care. We did our best to calm her anxiety, but inwardly we were quite skeptical. The infant’s chances were grim, to say the least.

In the weeks and months that followed, I was transferred to another service, but I was plagued by unwelcome, afflicting thoughts and images of what I had seen. I kept thinking of that newborn. Deprived of intelligent guidance, amid ignorance and poverty, malnourished and deficiently housed, what could possibly be his fate? The playing field is not level, regardless of the cant that politicians hypocritically dispense every day. Then, months later, I saw something that did away with all my pessimist ruminations. Marisela and her little boy─the feeble bantling had survived after all!─had come to the pediatric clinic, for counseling.

It happens sometimes, though rarely, that a single sight drives off our dreariest moods. Such is the power of vision. A casual sight did more than any elaborate reasoning could have done to restore my spirits: the mother seemed radiant, and the child, cuddling in her arms, nestling in her bosom, expressed that ineffable, placid joy of one that surrenders trustingly to a superior, benignant power. This was, no doubt, the sight of love. Love in its maternal variant, assuredly one of its noblest species. Its sublimity, its utter, untroubled serenity has been a favored theme of masterful painters, and it is right that this be so. Only to approach it they feel that even when depicting this human emotion they must resort to celestial personages, like Mary and her divine child (Fig. 2).

The message was as simple as the image that embodied it. It said that to the absolute “No!” of death, love invariably responds with a resounding “Yes!” For to the ultimate negation of death, love answers that nothing is ever finished; that there is always a new beginning; that what seemed to be the end of the journey, the finish line, is really a new point of departure; and that what we call death is actually rebirth. Love is, after all, the dynamic energy that ensures our mortal nature’s persistence; if not in the individual, certainly in the species. For love, as Diotima taught in the Platonic Banquet, is “desire of immortality.”

References

- W.B. Yeats: A Prayer for my Daughter. May be read at https://poets.org/poem/prayer-my-daughter.

F. GONZALEZ-CRUSSI, MD, is a retired pathologist and a frequent contributor to Hektoen International. For his literary work, see his Wikipedia.

Leave a Reply