Christopher Hubbard

Ohio, United States

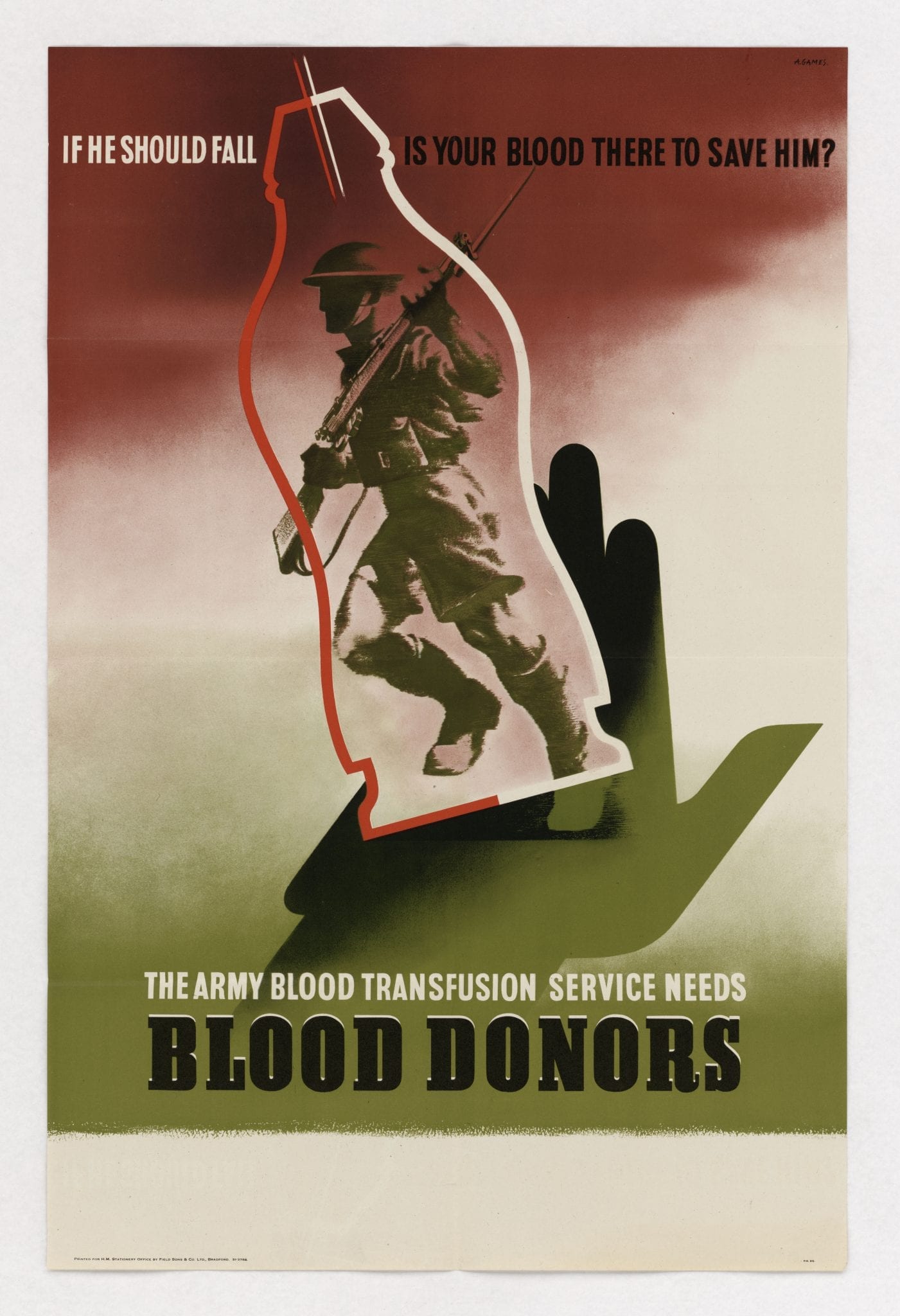

Image titled The Army Blood Transfusion Service Needs Blood Donors. Image located from the Digital Public Library of America. Rights: unrestricted.

Policies related to blood that were adopted in the U.S. during the early to mid-1900s produced cultural and legal effects for certain populations. In 1920, for example, the Hawaiian Homes Commission Act was passed by Congress,1 which modified how identity classifications and boundaries would be drawn up. The act classified an individual as Hawaiian if they were a “descendant with at least one-half blood quantum of individuals inhabiting the Hawaiian Islands prior to 1778.”2 Hence, fewer people would be recognized as indigenous, thereby reducing how many would have a legal claim to land on the grounds of being indigenous. The Indian Reorganization Act of 1934 operated along similar lines: aligning one’s bloodline to land, placing members of Indian tribes under federal jurisdiction.3

Another example involves blood banks, which did not fully come about until the 1930s—first in the Soviet Union in 1930 and then in the US in 1937.4 Fear of transfusing blood from a different race derived from findings in blood typing—specifically, that certain blood types are incompatible with others for transfusion purposes.5 The solution to this alleged problem came from being able to split blood into its components: plasma is untyped, according to the discourse propagated during WWII, unlike whole blood, permitting people to donate their blood for the war effort regardless of their blood type.6 However, the “processed plasma was also ‘typed’ according to the donor’s race.”7

What the above examples reveal is a historical tendency to view blood as possessing some feature regarding one’s race on which policy decisions and motivations could be based—particularly with regard to legal claims to land and determinations of identity—and to render race as biologically “definable” where such proof proved to be elusive at best.8 In effect, such practices blurred the lines of identity, diminishing the value or visibility of indigeneity. Such conflict might render for an individual with “racially mixed bodies” a difficulty to identify with either, leaving a “question about how [one’s] being is constituted,”9 especially when framed within the nation’s blood narrative. Another result was a type of medical cartography that monitored the movement of bodies of diverse populations and their blood; by placing the usability of one’s blood along racial lines under the framework of legal policies of the time, there was more biopolitical control over those bodies in a medical and legal sense.10

As one might expect, not everyone agreed with this perception or its outcomes; the NAACP, for example, protested such policies and “demand[ed] the right to participate in the war effort and the military practices it embodied” by being able to donate blood.11 Other activists adopted a more visual approach, whether scientific and objective or expressive and artistic. Horace R. Cayton Jr. was part of the former camp: he pointed out the visual politics at play in the segregationist policies, mocking the myth that “blood from African American donors is a different color than blood from donors of other races.”12 On the former camp’s side was activist Ana Mendieta and her artwork utilizing blood as paint. Blood has also been utilized in Indian art, not only for art itself but also for “mass political communication” and to express patriotism.13

One work from Mendieta, Blood Sign #2, part of her 1974 Blood Tracks, is a performance that shows her up against the wall with her hands above her. She then moves her hands to the bottom of the wall, leaving two vertical streaks of blood.14 Cathy Hannabach situates Mendieta’s work as “foreground[ing] the relationship between racialized female bodies, land, and blood,” while Body Tracks specifically “smears onto art gallery walls the female bodies of color often excluded from those spaces.”15

Reading her works as a map,16 they critically question nation-driven narratives founded on alleged racial differences to be found within one’s blood. Her blood work is “a project of radical cartography, producing an alternative mapping of bodies, land, and blood that resists various nationalisms.”17 Blood Sign #2, with its vertical lines, could be seen as marking and carving out a space for her in the national narratives informed by blood, either by showing that she bleeds the same as anyone else (echoing Cayton’s view above), or celebrating her racial identity while also serving as a polemic for questioning boundaries.

Such expressive and artistic displays of blood can be viewed as bioart, which addresses some issue or topic within biopolitics and biopower. Whether or not bioart, blood used for the respective piece of art produces “radical political commentary”18 and evokes a powerful image and latent anxiety over blood loss.19 When framed within a context of political, societal, or cultural critique, the use of blood in art becomes intertwined into the narrative of a nation.20

Within a Western context, the use of blood in art can be explained as a natural effect from bloody events from the twentieth century, but the works of Mendieta span cultural and national boundary lines.21 Against perceptions of identity produced within the US during the 1900s by portrayals of blood and heritage, Mendieta’s work “resisted and transformed”22 such blood-identity discourses, questioning the idea of the US being the “ultimate arbiter” of identity.23 Her work also dismantles the “view from above” that had been produced by controlling the biopolitical medical map of the movement of blood based on race,24 seeking to restore the autonomy of, for instance, those who desired to donate blood but could not because of their race.

The pressing question is: how can one properly acknowledge one’s mixed heritage and bloodline when policies in place actively denounce that bloodline? Mendieta’s bioart questioned those oppressive policies that devalued certain populations on the basis of their blood and conflated that identity with their legal right to land they inhabited or ability to donate blood. Her work, especially performances such as Blood Sign #2, also celebrated her bloodline (thereby compelling others to do the same by extension) by drafting up an alternative cartography of blood despite the cultural perceptions which manifested and were enforced by those policies.

Notes

- Cathy Hannabach, Blood Cultures: Medicine, Media, and Militarisms (Palgrave Macmillan, 2015), 46.

- HHCA, qtd. in Hannabach Cathy, Blood Cultures, 47.

- Ibid.

- Ibid, 13.

- Ibid, 17.

- Ibid, 18.

- Ibid, 20.

- Ibid, 20-22. The American Red Cross initially had a policy that separated blood based on the donor’s race, but due to social pressures of groups undertaking a civil rights approach, they changed their policy in 1950, over a decade before the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Other blood banks continued this segregative practice until 1964 on account of the Civil Rights Act.

- Elizabeth Archuleta. “Refiguring Indian Blood through Poetry, Photography, and Performance Art.” Studies in American Indian Literatures 17, no. 4 (2005): 3.

- Cathy Hannabach, Blood Cultures, 53.

- Ibid, 22.

- Ibid, 23.

- Jacob Copeman. “The art of bleeding: memory, martyrdom, and portraits in blood.” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute (2013): S150.

- Cathy Hannabach, Blood Cultures, 38.

- Ibid.

- Ibid, 41. Mendieta’s works as a map is an idea Hannabach derives from Mendieta’s writing: “I have been carrying on a dialogue between the landscape and the female body,” qtd. by Hannabach, 41.

- Ibid.

- Jacob Copeman. “The art of bleeding.” S151

- Ibid, S150.

- Ibid, see S150.

- Ibid, S151.

- Cathy Hannabach, Blood Cultures, 42.

- Ibid, 49.

- Ibid, 60.

References

- Archuleta, Elizabeth. “Refiguring Indian Blood through Poetry, Photography, and Performance Art.” Studies in American Indian Literatures 17, no. 4 (2005): 1-26.

- Copeman, Jacob. “The art of bleeding: memory, martyrdom, and portraits in blood.” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute (2013): S149-S171.

- Hannabach, Cathy. Blood Cultures: Medicine, Media, and Militarisms. Houndsmills, Basingstoke: Palgrave Pivot, 2015.

CHRISTOPHER HUBBARD holds a BA in philosophy and psychology and an MA in English. He has worked as a freelance writer and editor.

Submitted for the 2019–2020 Blood Writing Contest

Leave a Reply