Ryan Hill

Jamestown, Rhode Island, United States

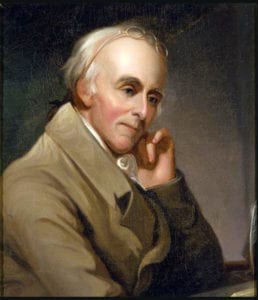

Portrait by Charles Willson Peale, Benjamin Rush, circa 1818. Independence National Historical Park. Via Wikimedia. Public domain.

Despite the adamant opposition he encountered from many of his contemporaries, Dr. Benjamin Rush was undeterred; he was certain that bloodletting was the most prudent of all medical procedures and remained faithful to the practice. The late eighteenth century doctor received harsh criticism for his excessive use of this treatment during yellow fever outbreaks in Philadelphia in the 1790s. Some went so far as to call his actions “murderous.” He was also mired in controversy over the amount of blood he had drawn from George Washington on the day of his death.1 Yet rather than relenting, Rush fought to clear his name and continued to advocate for the waning medical practice until his death.

Bloodletting, often referred to as “depletion therapy,” is the earliest form of therapeutic venesection and dates back more than 3,000 years. What is believed to have begun with the Egyptians persisted in the culture and medical practices of the Greeks, Romans, Asians, and Arabs, and continued through the Renaissance in Europe. Today, the practice is used only in treatments for a select few conditions, but during these bygone eras, it was considered a cure-all, related to the contemporary understanding of Galenic anatomy and the importance of blood.2 During Rush’s day, however, many began to look at the practice with great skepticism, if not rejecting it outright. Though the practice was not fully debunked until a couple of decades later, the findings of Vesalius and Harvey in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries exposed the significant errors of the Galenic interpretation of anatomy that underpinned practice.3 Furthermore, it was obvious to many of Rush’s contemporaries, who took a much more objective view of bloodletting, that the practice was doing more harm than good. So, given this shift in thinking, why did Dr. Rush, one of the most brilliant and educated men of his day, hold on to this near-obsolete practice so unswervingly, even in the face of opposing evidence? Taking the question a bit further, is there anything physicians can learn from his apparent intransigence today?

It would be easy to simply attribute Rush’s “blind eye” to his self-righteousness and stubbornness, as many have done over the past 200 years, but doing so dismisses other possible explanations which could reveal our own susceptibility to similar “blindness.” When examined through the lens of behavior science, it appears that what Rush experienced in refusing to see new evidence is not uncommon. Thomas Kuhn, in his seminal work The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, argued that most scientists, when given information that is contrary to the conventional wisdom, will try to reinterpret the information rather than abandon the current paradigm. In the centuries leading up to Dr. Rush’s practice, bloodletting fit perfectly into Kuhn’s definition of a paradigm. He considered it an “entire constellation of beliefs, values, techniques, and so on shared by the members of a given community.”4 These are deeply embedded assumptions, well-known and well-followed, and rarely questioned. Consequently, Kuhn asserted that it is often those who are younger or new in a profession who, “being little committed by prior practice to the traditional rules of normal science, are particularly likely to see that those rules no longer define a playable game and to conceive another set that can replace them.”5 These scientists are able to shift the paradigm rather than attempting to bend the evidence to fit the assumptions of the past. Perhaps Rush was stubborn, and maybe even self-righteous, but it was likely his inability to comprehend the shifting paradigm, rather than sheer stubbornness that tethered him so closely to the age-old belief in depletion therapy.

Dr. Rush was not alone in his inability to detect the shifting landscape of medicine. The practice of bloodletting continued unchanged through the mid-nineteenth century.6 However, this slow progression is not surprising; people have a tendency to trust their own views more than they do those of others. Studies conducted by Neil Weinstein and Hersh Shefrin demonstrate that people tend to be confident in what they believe and optimistic about the decisions they make. Their independent research identified optimism and overconfidence as a common human bias. They interviewed undergraduate business students and experienced executives and found that both had a strong bias toward believing that good things would happen to them over their peers and colleagues. When questioned about their futures, each individual felt like his or her own decisions would yield better results than the decisions of their peers.7 This optimism bias could obviously be useful in creating self-confidence and a willingness to accept risk; however, if everyone believes they are making the best decisions, it stands to reason that someone is not. Like Rush, most people are confident in their views and never pause to question if they may be promulgating poor techniques or exercising outdated practices. In short, overconfidence is a common trait, and it can be dangerous.

Rush’s behavior can further be understood by looking at the concept of confirmation bias. This common phenomenon occurs when people form a hypothesis and then gather information to support it, rather than looking at data objectively before forming a conclusion. According to behavioral economist Dr. Shahram Heshmat, “Once we have formed a view, we embrace information that confirms that view while ignoring, or rejecting, information that casts doubt on it.”8 Based on this concept, it is very possible that Rush was not simply beholden to an outgoing paradigm; rather he was, not surprisingly, only seeing the data that supported the practice of bloodletting. Despite the fact that he had seen countless deaths, he claimed that he had never lost a patient he had bled. In fact, he once stated that “Never before did I experience such a sublime joy as I now felt in contemplating the success of my remedies. It repaid me for all the toils and studies of my life.”9 His confirmation bias, a natural human tendency, clouded his views, creating an affirming interpretation of the evidence.

Perhaps Rush could have benefited from adopting a characteristic we now understand about blood itself. Recent research indicates that hemoglobin in the blood has a major part in a person’s ability to adapt to changes in altitude. It has long been understood that the body produces a greater number of oxygen-carrying red blood cells when at higher elevations where there is less oxygen available. It turns out that is only part of the story. Robert Roach, lead investigator and director of the Altitude Research Center at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus in Aurora, conducted research on this adaptive nature and found that hemoglobin, the proteins in the blood that carry oxygen, changed its behavior in higher elevations; the proteins actually held the red blood cells more tightly, keeping them in the bloodstream.10 So blood, rather than maintaining the status quo and ignoring changes in its environment, actually recognizes the shift and adjusts to enable the body to better thrive in the new conditions.

The adaptive behavior portrayed in blood would have been useful to Benjamin Rush and several other doctors who followed his lead in the years after science had shifted away from depletion therapy. Unfortunately, social science does not replicate the hard sciences in this way. Blood adapts when mitochondria in the skin sense hypoxic conditions and set off a “chain of events” that leads to greater production and retention of red blood cells.11 People, on the other hand, must change their minds to adapt. This process is far from automatic and can be very difficult, especially when countered by natural human bias. It takes a conscious and deliberate effort to reflect on and challenge assumptions.

Though it is difficult, it certainly can be done. An article in the Harvard Business Review lauded the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies, leaders in blood science and health, for the way in which they “reflect on their situation.” Despite their high-tempo and high-stakes work, they have developed a practice of slowing down enough to question their own practices. They do not cling purely to theory or past experiences to guide them, but take time to reflect and examine whether or not they are making the best decisions for the situations in which they are called to act.12 Because of this, the Red Cross continues to have significant impact throughout world and remains relevant.

What can physicians learn from Benjamin Rush, blood, and the Red Cross? In short, it is best to be open to change. Our understanding of the world around us is imperfect and our assumptions about it should be held loosely. New information and new ways of interpreting old information have the potential to alter the way we understand the world. Because of this, the best practitioners are not those that have a solid grasp on the facts, but those who are can adapt to the novelty that appears and make the most effective decisions. It is necessary to slow down when we sense a shifting paradigm and to question assumptions. Holding our scientific convictions loosely and being open to new ideas is essential in an uncertain and complex world.

References

- Gerry Greenstone, “The History of Bloodletting,” British Colombia Medical Journal, vol 52, no. 1, January-February 2010, 12-14. https://www.bcmj.org/premise/history-bloodletting

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Thomas S. Kuhn, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1996), 175.

- Ibid., 90.

- Greenstone, “The History of Bloodletting.”

- Edward Teach, “Avoiding Decision Traps,” CFO.com, June 17, 2004. https://search-proquest-com.usnwc.idm.oclc.org/docview/196860987?accountid=322

- Shahram Heshmat, “What is Confirmation Bias?,” Psychology Today, April 23, 2015. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/science-choice/201504/what-is-confirmation-bias

- Robert L. North, “Benjamin Rush, MD: Assassin or Beloved Healer?, Proceedings (Baylor University Medical Center) January 2000, 13(1), 45-59. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1312212/

- Richard A. Lovett, “Two Weeks in the Mountains Can Change Your Blood for Months,” Science, October 13, 2016. https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2016/10/two-weeks-mountains-can-change-your-blood-months

- Nora Dunne, “Uncovering How Cells Sense Oxygen Levels,” Feinberg School of Medicine News Center, April 7, 2016. https://news.feinberg.northwestern.edu/2016/04/uncovering-how-cells-sense-oxygen-levels/

- Jonathan Gosling and Henry Mintzberg, “The Five Minds of a Manager” Harvard Business Review, November 2003. https://hbr.org/2003/11/the-five-minds-of-a-manager

Lt Col RYAN HILL is a command pilot in the United States Air Force with over 2,600 hours in the A-10 and A29 aircraft. He has served tours in Afghanistan on the ground and in the air. He has a BS in Biology from the United States Air Force Academy, and three master’s degrees from the US Air Command and Staff College, the US Army’s School of Advanced Military Studies, and the US Naval War College. He is currently a Military Professor in the College of Leadership and Ethics at the US Naval War College.

Leave a Reply