Carys O’Neill

Chicago, IL

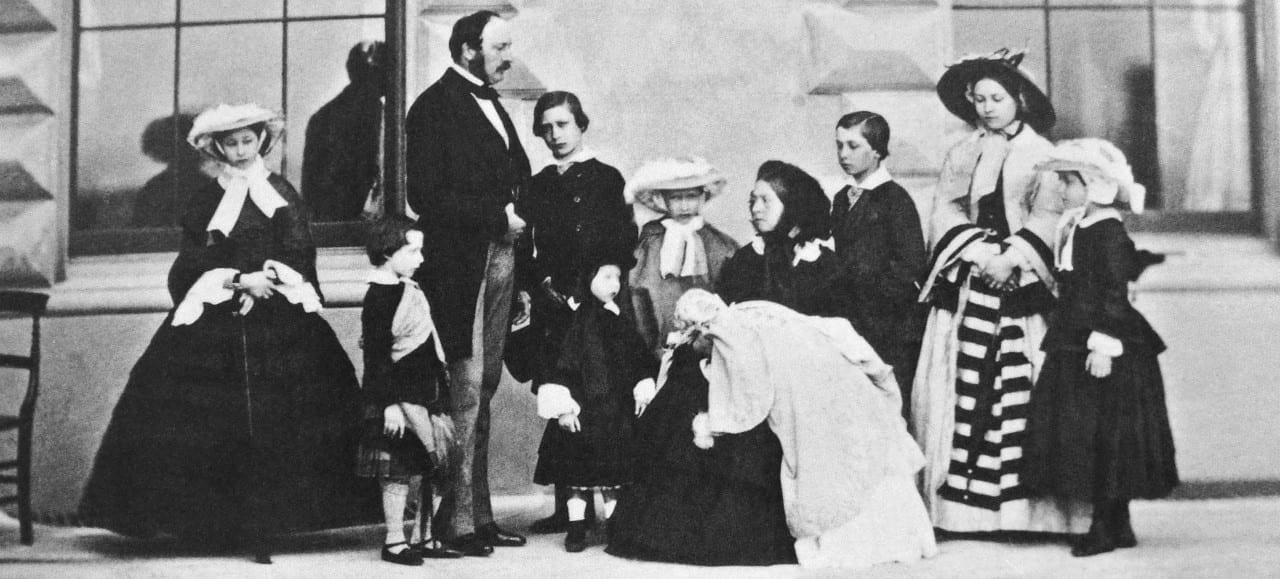

Known for restoring the reputation of a monarchy tarnished by the extravagance of her predecessors and reigniting a faith in empire through an embrace of civic and diplomatic duties, the legacy of Queen Victoria (1819–1901, r. 1837–1901) shaped a new role for the position of queen and the idea of her kingdom. At just five feet tall, she was a towering presence as a symbol of Britain, of ideal queenship, and of family. Together with her husband Albert and their nine children, Victoria came to symbolize a new, confident age of connection and progress throughout Europe. But this legacy was not limited to politics and high culture; when Victoria ascended to the throne in 1837, she brought with her a new kind of royal marker that would be passed down for generations, spreading from the beloved “Grandmother of Europe” through her own family to the farthest reaches of the German, Spanish, and Russian courts. Highly misunderstood in Queen Victoria’s day, hemophilia not only altered the trajectory of the queen’s own motherhood but heavily influenced the course of European history in the decades following her death.

When Victoria was born in 1819, there were no outward signs of hemophilia in the British royal family. Neither her mother nor her father were known to be carriers nor exhibited any outward symptoms of the disease. Following a healthy childhood, the young queen married her beloved cousin, Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, in 1840. It was not until 1853 and the birth of their eighth child and youngest son Leopold that the first signs of illness hit the royal household.

Leopold was described as a delicate child who bruised easily, particularly as he learned to walk. On 2 August 1859, Victoria shared an anxious exchange with King Leopold of Belgium, writing, “Your poor little namesake is again laid up with a bad knee from a fall — which appeared to be of no consequence. It is very sad for the poor Child — for I really fear he will never be able to enter any active service. This unfortunate defect . . . is often not outgrown & no remedy or medicine does it any good.”1 The prince continued to have accidents and was diagnosed by the queen’s physician, Dr. James Clark, with the bleeding tendency “haematophilia.”

Despite the diagnosis, little was known about the intricacies of blood-related illnesses in the nineteenth century. The phenomenon had been described by Philadelphia physician John Conrad Otto (1774–1844) as a familial bleeding disorder that affected male members, but his study was largely genealogical in nature, intending to trace the transmission of the disease back through families rather than explore its manifestations. He wrote in 1803, “If the least scratch is made on the skin of some of them, as mortal a hemorrhagy will eventually ensue as if the largest wound is inflicted.”2 Doctors largely believed that the blood vessels of those with hemophilia were simply more fragile. In fact, the term “haematophilia” was not coined until 1828, when Zurich University student Friedrich Hopff devised the term to describe the phenomenon Otto and others had brought to light. But as Victoria herself lamented, there was no treatment for the disease that severely limited the lifestyle and lifespan of her young son. Medical knowledge focused almost exclusively on the treatment of wounds and the prevention of life-threatening bleeding; from ice and poultices to splints and periods of indefinite bed rest, the management of symptoms was equally as ineffective as it was maddening. Victoria lived with continuous guilt, once writing, “No one knows the constant fear I am in about him.”3

Early attempts at management included the administration of lime, bone marrow, hydrogen peroxide, and gelatin to wounds, particularly in instances of surgery, but as the “defect” was in the blood itself rather than at the wound site, these treatments were almost always unsuccessful. The first transfusion to treat hemophilia was performed by English surgeon Samuel Armstrong Lane (1802–1892) in London in 1840, but transfusions remained incredibly risky and were largely dismissed by the medical establishment. The status quo for hemophilia research and treatment would not change until the Argentinian physician Alfredo Pavlovsky’s (1907–1984) discovery of different types of hemophilia over a century later.

In Leopold’s day, most people with hemophilia did not make it to adulthood. Those who did were usually crippled by the long-term effects of internal hemorrhages, particularly in the joints, making it one of the most painful diseases known to medicine at the turn of the twentieth century. Thanks to a careful upbringing under the watchful eye of his mother and access to some of the best doctors in Europe at her court, Leopold surpassed the average life expectancy of just thirteen. In 1882 he married Princess Helena (1861–1922) and the couple had a daughter, Princess Alice (1883–1981). She too was a carrier of the gene, passing it to her son Rupert (1907–1928) who died in a car accident at the age of twenty and a second son, Maurice (1910), who died in infancy. In 1884, Leopold died of a brain hemorrhage after a minor fall, leaving behind a pregnant Helena. Her second son, Prince Charles (1884–1954) was not afflicted.

Through Victoria’s daughter Alice (1843–1878), who married the future Louis IV of Hesse in 1862, seven more children were exposed to the potentially deadly inheritance that plagued her family. Two sons were born with the disease, one dying at the age of two, and two daughters were carriers. Alix, the future Tsarina of Russia (1872–1918), and Irene carried on Victoria’s legacy in the Russian and German courts. Through Victoria’s daughter Beatrice (1857–1954), at least one of three sons, Prince Leopold (1889–1922), was born a hemophiliac and a daughter, Victoria Eugenie, who married the Spanish King Alfonso XIII (1886–1941) in 1906, was a carrier. It is likely that hemophilia contributed to the untimely death of a second son, Prince Maurice (1891–1914), during the First World War.

As this lineage indicates, and as John Conrad Otto noted in 1803, hemophilia was more prevalent in males. We now know that the disease is a genetic disorder located on the sex-linked X chromosome. The trait is recessive, meaning that women, with two X chromosomes, must inherit the mutation from both mother and father for the disease to appear. Otherwise, they remain silent carriers, increasing the likelihood of passing the disease down to their sons, who only have a single X chromosome and thus incur a fifty percent chance of contracting hemophilia even if their father is not a carrier, as was the case with Victoria and Albert. As Victoria’s family showed no symptoms of the disease, it is believed that a spontaneous mutation on an X chromosome in either a parent at the time of the queen’s conception or the queen herself during her lifetime led to the introduction of the disease into the British royal family. Tests conducted on the remains of the Imperial Romanov Family of Russia, related to Victoria through her daughter Alice, in 2009 showed that Victoria’s great-grandson Tsarevich Alexei (1904–1918) suffered from the relatively rare hemophilia B, while his sister Anastasia (1901–1918) was a carrier.4

The deadly combination of a silent carrier and a tradition of political marriages and large royal families contributed to one of the most prominent transmissions of a genetic disease in medical history. From Victoria’s introduction of the “royal disease” to the British court, her daughter Alice’s passing of the gene to the German court, Alice’s daughter Alix’s marriage into the Russian royal family, and Victoria’s granddaughter Victoria Eugenie’s marriage into the Spanish royal family, four new strains of the disorder were spread across the Europe. The inheritance of the throne through Victoria’s eldest son Edward VII (1841–1910), who was unaffected, and the assassination of all of Alix’s children during the Russian Revolution of 1917–1918 spared the British and Russian courts from generations of future inheritance, but the Spanish lineage saw two more sons with the disease and another carrier daughter.

The last known descendant to suffer from the disease was Infante Don Gonzalo (1914–1934), who died in a car crash at nineteen. Today, no living members of reigning dynasties are known to have symptoms of hemophilia. However, with the possibility of silent carriers in many of Victoria’s great-granddaughters, there remains a small chance that the disease could appear again, especially in Princess Beatrice’s Spanish line. Although the disease weakened royal lineages and compromised the political stability of several prominent European houses, the attention brought by its prominent carriers encouraged the medical community, particularly in Britain, to learn more about the roots of the disease and its prevalence in the royal lineages of Europe and had a significant impact on the foresight surrounding royal marriages in the years following Victoria’s death. As Alan Rushton writes, “Public discussion of hemophilia transformed it from a rare medical phenomenon to a matter of national news. Practicing physicians, the royal family, and the general public all came to understand the clinical features and the hereditary nature of the problem [and] utilized this information to guide the marriages of their own children to prevent the spread of this dreaded bleeding disorder.”5 The legacy of hemophilia as the “royal disease” no longer captivates public memory as it once did, but as researchers and physicians continue to work toward a cure, the encouragement of a particular European matriarch and her hundreds of royal descendants is fuel for the fire.

Endnotes

- Quoted in Christopher Hibbert, Queen Victoria: A Personal History (New York: Basic Books, 2000), 402.

- John C. Otto, “An Account of an Hemorrhagic Disposition Existing in Certain Families,” The Medical Repository Vol. VI, No. 1 (1803), 1. https://genmedhist.eshg.org/digitised-resources/. Accessed 4 January 2020.

- Moniek, “Queen Victoria and Haemophilia,” History of Royal Women, 21 July 2019. Accessed 5 January 2020. https://www.historyofroyalwomen.com/the-year-of-queen-victoria- 2019/queen-victoria-and-haemophilia/.

- Evgeny Rogaev, Anastasia Grigorenko, Gulnaz Faskhutdinova, Ellen Kittler, and Yuri Moliaka, “Genotype Analysis Identifies the Cause of the “Royal Disease,” Science Vol. 326 No. 5954 (6 November 2009): 817. https://science.sciencemag.org/content/326/5954/817. Accessed 5 January 2020.

- Alan R. Rushton, “Leopold, the “Bleeder Prince” and Public Knowledge About Hemophilia in Victorian Britain,” Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences Vol. 67, No. 3 (July 2012): 457.

Works Cited

- Franchini, Massimo and Pier Mannuccio Mannucci. “The History of Hemophilia.” Seminars in Thrombosis and Hemostasis Vol. 40, No. 5 (2014): 571-576. https://www.thieme-connect.com/products/ejournals/abstract/10.1055/s-0034-1381232. Accessed 4 Jan 2020.

- Hibbert, Christopher. Queen Victoria: A Personal History. New York: Basic Books, 2000.

- Moniek. “Queen Victoria and Haemophilia.” History of Royal Women. 21 July 2019. Accessed 5 Jan 2020. https://www.historyofroyalwomen.com/the-year-of-queen-victoria- 2019/queen-victoria-and-haemophilia/.

- Offner, Susan. “Royal Hemophilia.” The American Biology Teacher Vol. 75, No. 9 (November/December 2013): 652-656.

- Otto, John C. “An Account of an Hemorrhagic Disposition Existing in Certain Families.” The Medical Repository. Vol. VI, No. 1 (1803), 1-4. https://genmedhist.eshg.org/digitised-resources/. Accessed 4 Jan 2020.

- Rogaev, Evgeny, Anastasia Grigorenko, Gulnaz Faskhutdinova, Ellen Kittler, and Yuri Moliaka. “Genotype Analysis Identifies the Cause of the “Royal Disease.” Science Vol. 326, No. 5954 (6 November 2009): 817. https://science.sciencemag.org/content/326/5954/817. Accessed 5 Jan 2020.

- Rushton, Alan R. “Leopold, the “Bleeder Prince” and Public Knowledge About Hemophilia in Victorian Britain.” Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences Vol. 67, No. 3 (July 2012): 457-490.

Image Source

Public domain; original photograph by Leonida Caldesi in Royal Collection, Royal Collection Trust, RCIN 2106422, Albumen Print Mounted on Card, from the collection of Albert Edward, Prince of Wales, https://www.rct.uk/collection/2106422/queen-victoria-and-prince-albert-with-their-nine-children-at-osborne

CARYS O’NEILL is a public historian working at the International Museum of Surgical Science in Chicago. She holds a bachelors degree in history from Furman University and recently completed a masters in public history and heritage management at the University of Central Florida. Her work critically evaluates the nature of representation in public spaces, particularly with reference to women, gender, and sexuality, as well as issues in historical interpretation, the production of heritage, and the formation of collective memory.

Submitted for the 2019–2020 Blood Writing Contest & Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 12, Issue 2 – Spring 2020

Leave a Reply