Emily Boyle

Dublin, Ireland

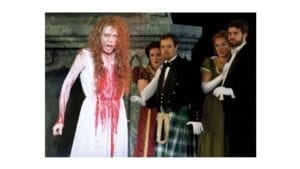

Lucia’s mad scene – Rachelle Durkin as Lucia during The Chautauqua Opera’s dress rehearsal for Lucia di Lammermoor. Photo by Michelle Kanaar.

In some professions, bloodstained clothing is a normal part of the job. The two jobs that come to mind principally are a butcher and a vascular surgeon, although the latter would probably prefer not to be associated with the former! In vascular surgery not every operation results in bloodstained scrubs, although for some procedures it is almost unavoidable, such as vascular trauma and open repair of a ruptured aortic aneurysm. It is not uncommon in such scenarios to lose more than the patient’s circulating blood volume while blood and blood products are being transfused rapidly to try and maintain circulation as the surgeon attempts to control the bleeding source. Blood loss is probably less dramatic in the elective setting, although it is not always a bad sign during a vascular procedure. When testing inflow through the bypass graft you have just fashioned, for example, accidentally spraying the assistant is a welcome indication of a well-functioning graft.

At least in modern-day surgery soiled gowns and scrubs are changed and washed. In the era before Joseph Lister, for example, surgeons wore their normal clothes while operating1 and the idea of changing clothes between patients (or any kind of hygienic measure) would have been laughed at. A surgeon would routinely arrive to start his operations in a blood-encrusted frock-coat.1,2 Little wonder that mortality rates were three to five times higher in hospital compared to a domestic setting.2

However in other scenarios, bloodstained clothing is more alarming, usually a sign that some violent activity has taken place, with the wearer either the victim, a witness, or perhaps most ominously, the perpetrator. Blood is often used on stage and on screen to suggest violence, add symbolism, and enhance the dramatic effect.

Many famous examples occur in opera. One such dramatic scene occurs in Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor. In the final act of this opera Lucia, the tragic heroine who has been forced into a marriage with someone she does not love, is led to believe her real lover has been unfaithful, and the shock makes her insane.3 She stabs her unfortunate husband in the bath. However this occurs offstage and in her famous mad scene, Lucia enters wearing a bloodstained wedding dress and sings a dramatic aria. Although the violent act is not shown, Lucia’s shocking appearance helps to convey the horror of what has just taken place and sets the scene for her famous descent into insanity (Fig 1). The juxtaposition of the red blood on the white dress mirrors the contrast between these violent events occurring on what should have been the joyful occasion of a wedding. The assembled guests look on in horror as Lucia wanders around the stage, singing.

Another operatic example occurs in Tosca. In this opera, Tosca’s lover Cavaradossi has been helping an escaped political prisoner of war. The villain of the piece, Scarpia, is in love with Tosca and desirous of any opportunity to dispatch with his competition. He is the chief of police, and has Cavaradossi arrested and tortured for information about the political prisoner and arranges that Tosca can hear what is taking place in an adjoining room. She gives Scarpia the information under duress when she hears the shouts of her lover. When Cavaradossi is brought back onstage he is battered and bloodied. Even before he opens his mouth, his appearance is alarming. Tosca is distraught and tries to console him. His appearance also foreshadows the violence to come in the opera. Unbeknownst to the characters at that point, Tosca will ultimately stab Scarpia, Cavaradossi will be executed, and Tosca will kill herself when she realizes Cavaradossi is dead. If operas were to be ranked by the body count of the principal characters, Tosca is probably in the lead.

The dramatic appearance of blood is frequently employed onstage, particularly by Shakespeare,4 but a famous scene where the blood is imagined occurs in Shakespeare’s Macbeth. In this well-known play, Macbeth and his wife commit many violent crimes in the pursuit of wealth and power. For most of the play it is Lady Macbeth who urges her husband onto acts of violence and bloodshed while he seems more reluctant. Events finally catch up with her in Act 5 when the enormity of what she and her husband have done eventually dawns on her. She becomes insane due to her guilt and imagines her hands are covered in blood which she is unable to wash off—“will these hands ne’er be clean?” In a metaphorical sense she certainly has blood on her hands, and more to come as her guilty conscience ultimately leads her to suicide.

Bloodstained clothes are used to great dramatic effect in film, in many different genres. War films, thrillers, action films, zombie films, vampire films—all frequently feature blood-soaked actors and scenery. One famous example is in Brian de Palma’s film of Stephen King’s novel Carrie. In this film, the teenaged Carrie is a loner, ostracized and bullied by her peers at school. There are many symbolic references to blood in the film, including menstruation and crucifixion, but these only lead towards the climax. In one of the film’s famous scenes, her classmates push Carrie over the edge by playing a cruel practical joke. At the school’s prom night, they arrange for Carrie to be chosen as the prom queen and at the moment of her crowning douse her in a bucket of pig’s blood. Although this does not physically injure her, the humiliation and shame enrage her and unleash her telekinetic abilities.5 Devastated by what has happened, she imagines all the students at the prom are complicit and laughing at her even though only a small group of bullies were responsible.5 Her rage causes her to lose control of her powers. Carnage ensues and most of the students and teachers at the prom are violently killed. The image of Carrie covered in blood has become famous and her appearance reflects her rage and the violence which is about to be unleashed. To quote Shakespeare, “blood will have blood.”

In another famous film scene, the appearance of two blood-soaked characters is completely at odds with their nonchalant behavior, and this contrast provides some of the black humor in the scene. In Quentin Tarantino’s thriller Pulp Fiction, one of the several plot lines follows two hitmen, played by John Travolta and Samuel L. Jackson. As they drive back from a job, John Travolta accidentally shoots their back-seat passenger in the face mid-conversation. Although the violent act is not overtly shown, the blood stains both in the car and on the clothes of the two characters convey the horror of what has occurred. Eager to avoid detection by the police, they drive to their nearest friend’s house in order to get the car off the road as quickly as possible. There, they proceed to have a coffee and chat as though they are on a break in an office. The appearance of the two characters in black and white suits that are soaked in blood as they discuss the merits of different brands of coffee in a very-laid back manner is darkly funny. It is clear that what would be calamitous events for most people are part of their daily routine and their laid-back demeanor is completely contrasted with their alarming appearance.

On the world stage, bloodstained clothing can be a testament of real acts of violence. There is a famous example following the assassination of President John F. Kennedy in November 1963, also since depicted in film. He had just arrived in Dallas and was being driven in an open-top car.6 Many people had come to catch a glimpse of the president and first lady, Jackie Kennedy. During the procession, gunshots rang out, fatally wounding the president. Jackie, who was sitting beside him was not physically injured but was covered in her husband’s blood and bone fragments. Barely alive when he arrived at the hospital, his head injury was catastrophic and he died shortly after. Jackie, who was likely in a state of shock, refused to leave his side during resuscitation attempts. After he was pronounced dead his body was flown back to Washington and before the flight took off, the new president, Lyndon Johnson, was sworn in. Jackie was asked if she wanted to change out of her bloodsoaked clothes but refused. She reportedly said, “I want them to see what they’ve done.”7 She is famously pictured at the swearing-in of the new president in her blood-soaked pink suit and apparently regretted later that she had wiped the blood off her face before the ceremony.7 For the rest of the day she refused to take off the suit. When Air Force One landed in Washington she insisted on leaving the plane by the front stairs where she would be most visible and was photographed many times on the journey home with her husband’s body. She did not remove her now famous pink suit until the following morning when she arrived back at the White House. The suit, which was never washed, is now in storage in the National Archives, where it will be kept privately until 2103 according to family wishes.8 On the day of the ending of her husband’s presidency, Jackie Kennedy kept the horror of the events center stage by reminding the world what had happened. And perhaps she also wanted to keep a part of her husband close.

It is clear that outside of the controlled vascular operating room, blood stains are both dramatic and ominous, and are best avoided in real life.

References

- Thomas B. Saints and Sinners – Robert Liston. Ann R Coll Surg Engl (Suppl) 2012; 94: 64–65

- Fitzharris L. The Butchering Art: Joseph Lister’s Quest to Transform the Grisly World of Victorian Medicine. New York, Penguin History (Allen Lane) 2018

- Ashley T. Out of their minds. At https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2002/jul/05/shopping.artsfeatures

- Kirschbaum, L. Shakespeare’s Stage Blood and Its Critical Significance. PMLA 1949; 64(3), 517-529. doi:10.2307/459751

- Franssen R. Bloody Horror! The Symbolic Meaning of Blood in Stephen King’s Carrie at http://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:918009/FULLTEXT01.pdf

- Swanson JL. “The President Has Been Shot!”: The Assassination of John F. Kennedy. New York, Scholastic Press , 2013

- Andersen C. Those Few Precious Years. New York, Gallery Books, (Simon and Schuster) 2016

- https://www.vintag.es/2017/08/whatever-happened-to-jackies-blood.html

EMILY BOYLE, MD, FRCS, FEBVS, received her medical degree in 2004 from the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland. Having worked and trained in many hospitals around Ireland, she is now a consultant vascular surgeon in Tallaght University Hospital in Dublin.

Submitted for the 2019–2020 Blood Writing Contest

Leave a Reply