John Graham-Pole

Clydesdale, NS, Canada

Life blood: Humor and health

In 1960, I entered St. Bartholomew’s Medical School on a full classics scholarship. I was a devotee of Hippocrates, with high hopes of embarking on a path of uniting medical science with the healing arts. “Let food be thy medicine and medicine be thy food” was my credo, and I knew that those 300 medicinal plants for which the father of medicine had found medicinal uses would keep my bodily humors—blood, black bile, yellow bile, phlegm—balanced into ripe old age.

Such irony! Casting asunder the individual elements of human blood came to define my life as a medical scientist. I was six years into retirement before I made my pilgrimage to sit under Hippocrates’ plane treei and reflect on my life’s journey in art and science. TS Eliot’s words struck home: “. . . the end of all our exploring will be to arrive where we started and know the place for the first time.” As I rested on one of the Asclepian temple’s fallen columns, a passing descendant of Hippocrates blessed me with a cluster of sacred tea to guarantee my immortality.ii

Blood lines: Uniting and parting

Prenatal life began for me—like everyone else’s—when my artist-mother and scientist-father contributed a gamete each to create my very first zygote. A week later my hundred-cell embryo embedded itself in my mother’s womb, to be severed thirty-eight weeks on when she thrust my trillion-cell self out into the world. The family unit broke apart when my father disappeared, leaving her a single parent of four. I was two years old. It was not till my twenty-first birthday that my father sought me out: we sat silent through four hours of Lawrence of Arabia.

My earthly parting from my mother came when I was twelve. It took the words she had penned to “my four beloveds” ten days before her death to reunite us in spirit: “John, I think you will choose medicine.” My life’s deepest irony is that her letter stayed sealed for fifty-two years. I made my career choice of pediatric hematology and oncology unaware her spirit had been guiding me from the urn.

Bloodletting and infusing

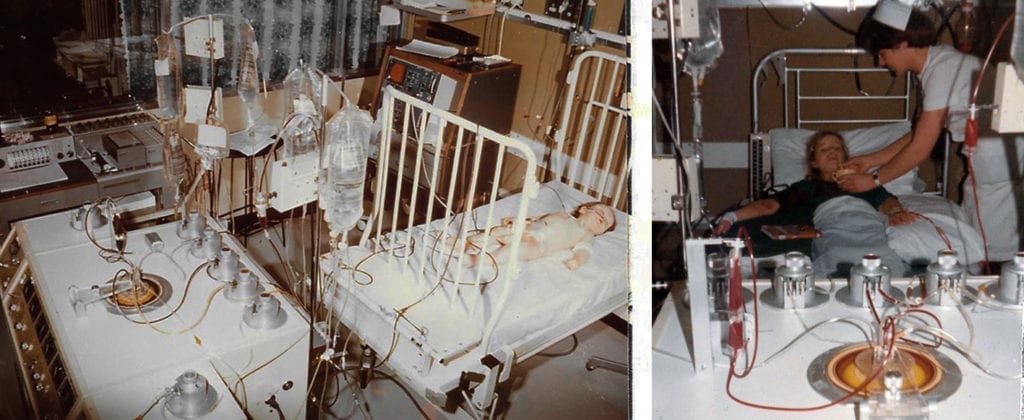

Separating and uniting came to infuse my working life. I parted with early patients in death, and reunited with later ones who thrived and brought their own babes-in-arms to meet me.iii My laboratory work focused first on separating red cells, white cells, and plasma with one of Britain’s first continuous-flow cell separators; later, on harvesting hemopoietic stem cells from bone marrow and placenta for allogeneic and autologous transplants.

Clint Malone, a “midnight cowboy” techie who sported fresh jeans, Stetson, and western boots each day, brought the American Instrument Company Celltrifuge from Houston to the University of Glasgow. The day before his departure an emergency room intern called me to a twelve-year-old girl in profound shock. She was delirious from E. coli septicemia and neutropenic from acute leukemia. This was 1972: few survived such mortal assault. But her parents’ neutrophils—a total of 100-million over three days—brought total recovery. Over the next four years I gave neutrophil infusions to thirty-one septic children with leukemia.1 I infused lymphocytes into lymphopenic children with pneumocystis infections and congenital enzyme deficiencies. I treated children with refractory cancers with parental lymphocytes sensitized in vitro to their children’s cancer cells.2 I started freezing surplus white cells in liquid nitrogen, a technique that proved invaluable ten years later when I embarked on bone marrow stem cell cryopreservation at the first US pediatric transplant center in Cleveland.3

Continuous flow plasmapheresis enabled parents to give massive platelet infusions to profoundly thrombocytopenic children. I plasmapheresed a twelve-month-old boy with hepatic encephalopathy and a nine-year-old girl with SSPEiv after measles.

Then a totally new use for plasmapheresis presented itself when I got a call from a woman in Iceland who had lost three babies in utero from severe Rh-isoimmunization. She was twenty weeks pregnant with yet another affected fetus.

“Can plasmapheresis work for me?” she asked in perfect English.

She made twelve weekly flights from Reykjavik to Glasgow for six-liter plasma exchanges per trip.4 Her anti-Rh antibody and amniotic fluid bilirubin fell steadily until she delivered her first healthy baby at thirty-six weeks. We adopted the same approach for eight other affected pregnant moms and babies.

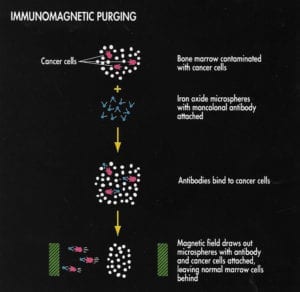

The bone marrow transplant program I established in Cleveland in 1978 achieved the first cures in children with refractory neuroblastoma.5 Because most of these autologous bone marrows contained cancer cells, we “purged” them with immunomagnets before reinfusing the healthy stem cells.6,7

Blood relations: science and art

In 1976 I submitted my dissertation for my MD doctoratev,8 to my alma mater. At my oral defense the committee chairman announced, “I can’t accept your data on immunotherapy for treating children with cancer. So we’ll award your doctorate on condition you tear out page 160 from all four copies.” He handed me a pair of scissors and I summarily reduced each bound volume from 276 to 275 pages. But his persnickety decision—history proved my data sound!—squelched my enthusiasm for writing science. The impenetrable way journal editors demanded it be written reinforced this: re-reading a paper I had published three months earlier left me baffled about what I had been trying to say.

It came to a head when I caught myself gazing in frustration at my third revision of an article to Blood—the most peer-reviewed publication in the field of hematology. Although the symbol ≤0.001 seemed suddenly opaque, the words—leucostasis, plasmapheresis, immunoglobulin, hemopoietic, corpuscle, and countless others—still beguiled me. So I laid aside my fifty-fifth scientific publication and penned two sonnets inspired by fifteen years of hematology.

Ruby Red9

Her body fragrant from alveolar showers,

floats forth our curvy spheroid, Ruby Red;

her cheeks aglow with O2’s heartening powers

she charts her course for that far capillary bed.

The rosy roller rides the aortic road,

unmindful of her distant splenic fate,

through arteriolar backwoods bears her load—

the wastrel CO2 recoils too late.

But macrocytic changes lie ahead,

and days of crenation speedily ensue;

she’s targeted for pyknosis, so ’tis said:

our once-pink heroine fades a waning blue.

And so poor Ruby meets her final test,

in gentle hemolysis rolled to rest.

Ode to Lou and Will10

I tell you the tale of two fine friends of mine

named Louis Leuk and his buddy Willy White,

who never miss a chance to wine and dine

on parasites who venture forth at night.

Old Will and Lou can squeeze through any crack

to phagocytose E. coli’s by the bunch,

for they love a really buggy kind of snack,

and streptococci make a perfect lunch.

They’ll catch ’em nappin’ in their mouldrin’ lairs,

for they are sniffin’ snatchin’ kinda men,

and microbes kneel to say their rottin’ prayers

before ’em as they chemotax their den.

So let us to Will and Louis proffer praise,

and love them for their antimicrobial ways.

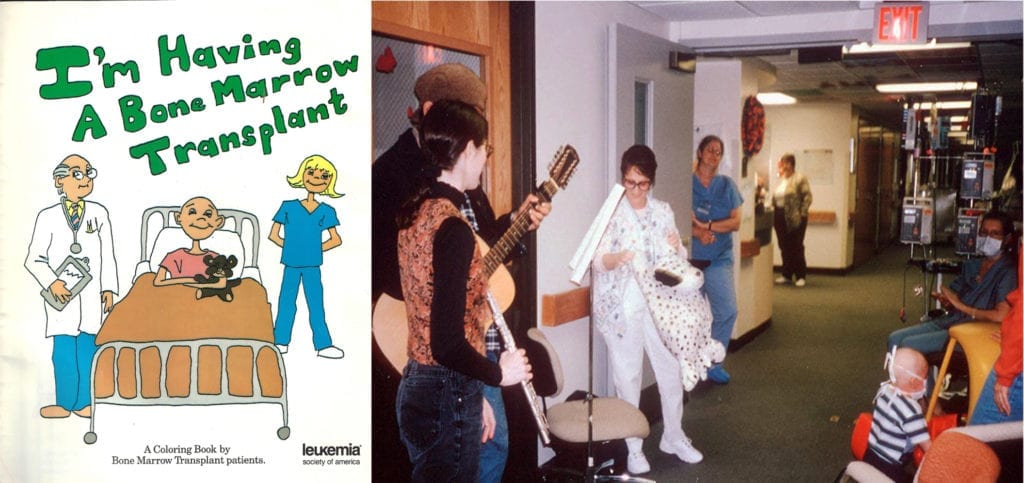

I mailed the final draft of the scientific paper to Blood’s editor the next morning. But that was it. I switched all my science energies into art. I invited artists of every stripe into the University of Florida’s tertiary medical center to paint and play, recite and perform, sing and dance, at the bedsides of the sick.11

By retirement I had come full circle. In my Last Lecture I reflected that medicine unfolds as science and art in reciprocity.12 I seemingly convinced a few colleagues. The pediatric department chair wrote in his testimonial to my medical memoir: “Through his introspective lens and knack for story-telling, Graham-Pole reminds us that the seeming conflicts between science and art, objective observation and subjective narration, often melt and mingle as we appreciate their fundamental interdependence.”13

Our life blood: A covenant of reciprocity

In the years I spent separating blood’s humors to treat ill children—reducing the whole to its totally distinct elements—I did not question why our Creator had placed them in such intimate unity within a single organ. Then a fourteen-year-old with sickle cell disease developed bilateral lung infarctions and pneumonia, and opened my eyes to the vital reciprocity of these individual components. His red cells’ irreversible sickling caused inexorable hypoxia and totally blocked any defensive incursion by his neutrophils, lymphocytes, macrophages, or immunoglobulins. His death from anoxia and refractory pneumonia was a painful lesson: absent nature’s rules of reciprocity, we mere humans stand helpless.

Contemporary medicine has impelled us toward a Newtonian separation of our bodily parts from their whole—and the arts from the sciences. Yet two-and-a-half millennia on from Hippocrates, the Greek sage remains a staple of both medical science and culinary art. Indigenous people continue to honor reciprocity for healing of body, mind, and spirit: witness ceremonial smudging with sage and other medicinal plants. Plant scientist Robin Kimmerer teaches us Mother Earth’s covenant of reciprocity through the indigenous parable of the “Three Sisters” Corn, Bean, and Squash.14 Plant these three seeds together in spring and watch synergy at work. Corn takes on water fast and pushes out her first stems, which grow tall and solitary. By and by, Bean’s heart-shaped leaves begin to entwine about Corn, meanwhile activating vital nitrogen underground from the Rhizobium bacteria clinging to her roots. Squash, the pokey youngest sister, finally emerges to extend her broad-lobed leaves and hold earth’s moisture in while keeping weeds and marauding caterpillars out.

Nature reminds us of our interdependence wherever we look. Healing demands right relationship and gratitude for the synergy of our separate gifts.

Art on the bone marrow transplant center. Left: Coloring book created by a 19-year-old patient, published by the Leukemia Society; Right: Nurse dancing to musicians between isolation rooms while patients look on

End notes

- The “Tree of Hippocrates” resides in the center of town on the island of Cos. It is here Hippocrates is said to have taught his pupils the art of medicine. The current plane tree is about 500 years old and may be a descendant of the original tree.

- Sage, sometimes known as “Hippocrates’ tea,” was a sacred medicinal herb in Classical Greece, believed to ensure immortality.

- Entering medical school in 1960, I knew of no child being cured of cancer. By the time of my retirement in 2007, the cure rate was 80%.

- SSPE = subacute sclerosing panencephalitis, a rare but usually fatal complication of measles

- In the UK, the MD degree is equivalent to a PhD, and is conferred on physicians for a body of postgraduate work.

- The images of the children are published with their parents’ permission.

References

- Graham-Pole J, Davie M, Kershaw, et al. Granulocyte transfusion in treatment of infected neutropenic children. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 1976;51:521-527.

- Graham-Pole J, Davie M, Willoughby M. Cryopreservation of human granulocytes in liquid nitrogen. J Clinical Pathology. 1977;30:758-762.

- Graham-Pole J, Ogg L, Ross C, et al. Sensitization of neuroblastoma patients and related and unrelated contacts to neuroblastoma extracts. 1976;1:1376-1379.

- Graham-Pole J, Barr W, Willoughby M. Continuous-flow plasmapheresis in management of severe rhesus disease. British Medical Journal. 1977;1:1185-1188.

- Graham-Pole J, Lazarus H, Herzig R, et al. High-dose melphalan therapy for the treatment of children with refractory neuroblastoma and Ewing’s sarcoma. Amer J Pediatric Hematology/Oncology. 1984;6:17-26.

- Graham-Pole J, Gee A, Janssen W, Lee C, Gross S. Immunomagnetic purging of bone marrow: A model for negative cell selection. Amer J Pediatric Hematology/Oncology. 1990;12:257-261.

- Graham-Pole J, Gee A, Emerson S, et al. Myeloablative chemoradiotherapy and autologous bone marrow infusions for treatment of neuroblastoma: Factors influencing engraftment. 1991;78:1607-1614.

- Graham-Pole J. Doctoral dissertation. Continuous flow centrifugation of whole blood: Applications to the treatment of diseases of children. University of London; 1978.

- Graham-Pole J. Ruby Red. In Quick: A pediatrician’s illustrated poetry. Lincoln, NE: Writers Club Press; p.35, 2002.

- Graham-Pole J. Ode to Lou and Will. In Quick: A pediatrician’s illustrated poetry. Lincoln, NE: Writers Club Press; p.36, 2002.

- Graham-Pole J. Illness and the art of creative self-expression. Oakland: New Harbinger Publications; 2000.

- Graham-Pole J. What’s known, what’s real, what’s good: Reflections on forty years of science and art in medicine. Last Lecture given at the University of Florida Center for Spirituality & Health, 2007. Retrieved January 4, 2020 from https://spiritualityandhealth.ufl.edu/events-speakers/john-graham-pole/

- Graham-Pole J. Creating. In Journeys with a thousand heroes: A child oncologist’s story. Decatur, GA: Wising Up Press; pp.177-200, 2018.

- Kimmerer RW. The three sisters. In Braiding sweetgrass. Minneapolis: Milkweed Editions; pp.128-140, 2013.

JOHN GRAHAM-POLE, MD, MRCP-UK, ABHM, a graduate of University of London. He has worked in pediatric hematology and oncology at four universities, co-directed bone marrow transplant units at Case Western University and University of Florida, and co-created Centers for Arts Medicine (www.arts.ufl.edu) and Spirituality & Health (www.spiritualityandhealth.ufl.edu). Dr. Graham-Pole has published eight books: Illness and the Art of Creative Self-Expression; Physical; Quick: A Pediatrician’s Illustrated Poetry; On Wings of Spirit; The Arts & Health; Journeys with A Thousand Heroes; The People’s Photo Album; and Blood Work. He is co-publisher with his wife, Dorothy Lander, of Harp: The People’s Press, which produces non-academic works on art and health.

Submitted for the 2019–2020 Blood Writing Contest

Leave a Reply