Eva Kitri Mutch Stoddart

Saigon, Vietnam

Blood oozes allure. The elixir of life, viscous and dramatic scarlet, courses through the veins of every living human. Blood has been viewed as sacred for centuries. Aristocrats used to sip at it to stoke their youth and vitality. Bram Stoker’s quintessential vampire novel, the revered Dracula, was published in 1897. Since at least the 1970s, blood has been used in visual art to explore topics such as violence, gender, and race. Almost every horror movie boasts abundant gore for the viewers’ pleasure, and all classic film-goers must remember the hypnotic red waves splashing across the hotel foyer in The Shining. In the candid words of the poet Goethe, “Blood is a juice of a very special kind.”1

Each adult has about nine pints of blood quietly circulating under their skin. It is our own. But throughout history we have considered the possibility and implications of sharing one’s blood with someone else. If losing too much blood kills you, it is logical to think we could borrow a little.

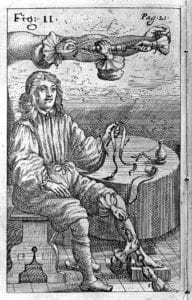

The first known attempt at sharing blood took place in Rome in 1492 as “good natured, incompetent” Pope Innocent VIII, who had fallen into a coma, was bathed in and fed the blood of three ten-year-old Jewish boys. These children had been coaxed into the arrangement with the promise of a ducat (gold coin) each for their services. Alas, no ducats were exchanged as all four parties died.2 There has been speculation that this event never actually happened because blood circulation was not discovered until the seventeenth century.

Research on the subject began or at least became more sophisticated with the 1628 discovery of the circulation by William Harvey, physician to James I, Charles I, and Francis Bacon. The doctor was particularly friendly with Charles, who would allow him to experiment on herds of deer and discuss his discoveries with him.3

From this discovery up until World War I there were a series of direct blood transfusions attempted, with about a fifty percent success rate. Things improved in the twentieth century, as by 1902 four distinct blood groups had been discovered, and by 1907 cross-matching donors to recipients had caught on. Even so, the equipment and logistics to perform a direct blood transfer remained difficult, and another major hurdle to patient survival was the possibility of clotting. World War I was the catalyst for figuring out some of the remaining kinks of transfusion.4

In 1914 it was established that adding sodium citrate to blood and refrigerating it would stop it from clotting and preserve it for future use. This discovery underpins the practice of blood donation, storage, and transfusion today. On 1 January 1916, Osward Hope Robertson, a medical researcher and US Army Officer, performed the first ever successful, non-direct blood transfusion. This was facilitated by storing blood using a glucose citrate solution, meaning that Robertson is generally heralded as the creator of the world’s first blood bank.

Before blood banks, a physician would have to undertake the lengthy process of cross-matching a patient’s blood with that of the patient’s willing friends and family to work out an appropriate match, and then have donor and recipient shoulder-to-shoulder as the blood was directly flooded from one body to the other. This process is very different today, with plentiful storage, contractual agreements, and more frequent transfusions. Blood has become a huge industry. The purity and nobility of blood donation is now juxtaposed against standard economic forces.

We can thank the Red Cross for normalizing blood transfusion, turning it from a somewhat disturbing medical practice to a well-organized and noble venture. The beginning of this normalization process was a Red Cross campaign called “Blood for Britain,” which began in New York City in 1940. It was difficult for the organization to gauge how much public interest there would be, but they campaigned with advertisements on radio, in magazines, and in newspapers. The idea was to encourage people to call for an appointment, where they would have staff explain the process in as much detail as possible.5 To alleviate fear, The Red Cross would also send volunteers called “Gray Ladies” to the hospitals to act as hostesses for the donors, offering refreshments such as whiskey afterwards and to generally “lift the spirits” of those donating. The women were said to introduce an air of “determined martyrdom,” part of an overall sentiment that would shape the perception of blood donation to this day. The transparent and well-organized process established the Red Cross as a professional and trustworthy organization, a reputation they have retained.

While the Red Cross works off volunteer donations, in the United States there are not actually laws prohibiting paid blood donations. Hospitals are just unlikely to buy it, and being literal “blood money” people tend to feel an ethical objection to the arguably exploitative idea of paying someone for a part of themselves. However, plasma is a quickly-growing segment of the blood products market, valued for its long shelf life, and plasma donors are usually paid. This is because plasma never goes directly to someone else, but is broken down into a range of proteins. At each stage of the process the plasma is tested, so the risk of disease transfer is much lower.6 Even so, concern has been raised about the ethics of the idea, since plasma donations are not easy on the body. The idea that people of a lower socioeconomic class may being forced by financial reasons to go through physical pain to sell parts of themselves is troubling.

Ethical and practical issues make one wonder about the future of the blood industry. We are living in a time of lab-grown meat, internal organs, and babies. Blood definitely seems like something that could fit into that class. Of course, blood substitutes have always been an alluring concept, and substitutes such as beer, milk, urine, and plant resins were tested as replacements in the years between Harvey’s discovery of circulation until the turn of the twentieth century. In the seventeenth century, Sir Christopher Wren suggested wine and opium, and it is no wonder he is more appreciated for his invention of the IV needle than that idea. Around the 1800s, more refined replacements such as saline solutions and animal plasma became available, and eventually synthetic products.

For a blood substitute to be useful it must fit some criteria: it must not cause any negative reaction, it must transport oxygen, and it must have a decent shelf life. In the modern world, there are two channels of blood substitute research. One is perfluorocarbons, and the other is hemoglobin-based products. For each of these options there are both practical and bureaucratic issues, although this is an area of interest for the future of medicine.7

In the meantime, we continue to rely on volunteer blood donations. The Red Cross has established that blood is something both shared and private. If you have not considered donating, give it some thought. A tiny needle is a small price to pay for saving lives.

Endnotes

- Katharina Rose Luise Schmitt, Oliver Miera, Felix Berger, “Blood: a very special juice. The good and the evil,” European Journal of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery, 45, 6. (2014): 1058–1059. https://doi.org/10.1093/ejcts/ezt595

- C. R. “Blood Transfusion in 1492?” JAMA. LXII, 8. (1914) :633. doi:10.1001/jama.1914.02560330051028

- Encyclopedia Britannica, s.v. “William Harvey,” accessed January 14, 2020, https://www.britannica.com/biography/William-Harvey

- Encyclopedia Britannica, s.v. “The Strange, Grisly History of the First Blood Transfusion,” accessed January 14, 2020, https://www.britannica.com/story/the-strange-grisly-history-of-the-first-blood-transfusion

- Kara W. Swanson, Banking On The Body (Massachussetts: Harvard University Press, 2014), 49-84.

- Elizabeth Preston, “Why You Get Paid To Donate Plasma And Not Blood,” STAT, accessed January 13 2020, https://www.statnews.com/2016/01/22/paid-plasma-not-blood/

- Suman Sarkar, “Artificial Blood” Indian J Crit Care Med. 12, 3.(2008): 140-144. doi: 10.4103/0972-5229.43685

EVA KITRI MUTCH STODDART graduated with a Bachelor of Arts in English and linguistics from Otago, New Zealand. She holds a fascination with biology and its connection to the arts, and strives to use readable writing to bridge a perceptual gap between the human body and mind. She lives in Saigon.

Submitted for the 2019–2020 Blood Writing Contest

Leave a Reply