Emily Cline

Montréal, QC, Canada

Upon her neck and breast was blood, and upon her throat were the marks of teeth having opened the vein:—to this the men pointed, crying, simultaneously struck with horror, “A Vampyre! a Vampyre!” — The Vampyre, John William Polidori

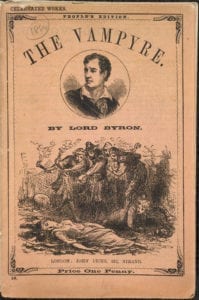

John William Polidori’s The Vampyre, published in 1819, established the conventions of the vampire genre. Though Polidori did draw his inspiration from Lord Byron’s “Augustus Darvell,” the story was wrongfully attributed to Byron by publisher Henry Colburn. This People’s illustrated edition, published in London ca. 1884 and illustrated by F. Gilbert, retains the wrongful attribution.8

With this image Polidori introduces the conventions of the modern vampire story. The physicality of a vampire attack—bloody breast, open vein, teeth—typifies the embodied aspect of the Gothic form; however, the macabre makeup of a vampire represents also a psychological conundrum. These oxymoronic creatures, the living dead, subsist on human blood by draining it from living bodies. Situated between life and death their status is ambiguous; thus the vampire stories are fraught with the complexities of negotiating the transition between the human animate body and the lifeless corpse. This suggestion that a being could move freely between states, encapsulates Freud’s theory of “intellectual uncertainty.”1 That is, the audience at once recognizes itself in the humanoid form of the vampire and recoils from what is unfamiliar and strange in the creature, its sanguinary appetite.

The pioneers of the Gothic genre were the original masters of the uncanny; in fact, it was an 1816 gathering of Gothic greats Mary Shelley, Percy Bysshe Shelley, Lord Byron, and John Polidori that famously churned out two new genres: the sci-fi thriller Frankenstein and Polidori’s The Vampyre—a re-“vamped” version of Lord Byron’s unfinished “Augustus Darvell” (1819). In Byron’s lesser-known “fragment,” the character Augustus Darvell dies, the narrator having immediately “perceived that he was dead.”2 He is convinced that his perception is true as he is confronted with the evidence of decay: “I was shocked with the sudden certainty which could not be mistaken—his countenance in a few minutes became nearly black.”3 The discoloration provides the outward evidence that Darvell’s heart has stopped pumping. Without the flow of blood, a corpse loses its humanity. In Polidori’s continuation in The Vampyre, however, the evidence of the senses is not to be trusted: “Lord Ruthven again before him […] He roused himself, he could not believe it possible—the dead rise again!”4 The risen dead defies natural laws and disrupts death’s finality and confronts the living with something unfamiliar and unsettling that can yet look and act human. However, successful upkeep of the human façade comes at the expense of blood, and ironically the vampire’s uncanniness aids his parasitic aim.

It is in fact Lord Ruthven’s lack of vitality—his “dead grey eye”5—that rather than excluding him from society assists his invasion into the domestic space. The narrator explains, “His peculiarities caused him to be invited to every house; all wished to see him.”6 The vampire’s successful infiltration of society and his ability to pass as human renders the danger unrecognizable, putting the most vulnerable members of society at risk. Ruthven’s “irresistible powers of seduction” cause the death and downfall of the young women with whom he comes into contact.7 The vampire’s unquenchable thirst is conflated with sexual appetite as the creature’s bloodlust becomes undeniable: “when they arrived, it was too late. Lord Ruthven had disappeared, and Aubrey’s sister had glutted the thirst of a VAMPYRE!”8 Helen Bailie acknowledges that the vampire’s sexual act “is also coded in the act of taking blood in the penetration of the vampire’s teeth without actual intercourse taking place. In the paranormal romance, there is nothing symbolic about the taking of blood but rather it becomes a necessary element of the sexual relationship.”9 Ruthven’s mesmeric powers and his gluttony threaten the social order from within. His relationships with women are unproductive, ruining reputations, marriage prospects, and innocence, and ultimately leading to death. Ruthven’s relationships, particularly in his marriage, are unproductive in a literal sense as well—undead as he is, his sexual desire is essentially necrophilic and therefore sterile. The false equation of Ruthven’s thirst with lust not only highlights sexual power dynamics, but also underscores his corruption of those he comes into contact with, since his victims also develop unnatural appetites in desiring the dead.

This fascination with the physicality of the dead lies latent in several contemporaneous stories of the macabre. For example, two stories—“The Victim,” published anonymously, and “My Hobby,—Rather” by N. P. Wills—published in the New Monthly Magazine in 1831 and 1834 both prominently feature sexualized female corpses. In the first, a story about a medical student who is sketching a stolen cadaver, the corpse figures as the “ideal picture of female loveliness”;10 in the latter, a student sits up for a nighttime vigil with a corpse, which to his mind “mingles with every conception of female beauty.”11 But the illusion of beauty is shattered when a cat attacks the corpse, which bleeds profusely: “to my horror, the half-covered and bloody corpse rose upright.”12 The student’s repulsion is prompted by the appearance of blood, an unwelcome indicator of life that is entirely incongruent with the situation of the wake. Indeed, Freud contends that it is in the “highest degree uncanny” when one “doubts whether an apparently animate being is really alive; or conversely whether a lifeless object might not be in fact animate.”13 The bleeding corpse, like the undead figure of Lord Ruthven is a memento mori that brings existential questions to the fore as the recently deceased corpse is not yet devoid of human potential.

The prospect of reanimation is further explored in another short story, “The Post-mortem Recollections of a Medical Lecturer,” in which the narrator—a medical lecturer—draws on the body’s “latent vitality” to reanimate himself.14 He explains the relationship between vitality and circulation: “If the heart could be so subjected to the principle of volition, as that, yielding to its impulse, it would again transmit the blood along its accustomed channels, and that then the lungs should be brought to act upon the blood by the same agency, the other functions of the body would more readily be restored.”15 The moment of reanimation is again inseparable from bloodshed as he experiences “one violent, convulsive throe, which brought the blood from my mouth and eyes.”16 This story uses scientific rationale to increase the Freudian “intellectual uncertainty” behind the mechanics of reanimation, using medical terminology to make the myth seem more realistic.

The vampire story perverts the scientific reanimation by removing the requisite blood from an internal to an external source. Thus, while a human corpse, even a reanimated one, may be uncanny, it is the pseudo-cannibalistic craving that makes the vampire one of the most fascinating and fearsome of creatures. The vampire, particularly the Romantic version conjured up by Byron and Polidori, at once seduces and repulses. The vampire’s human appearance hides a monstrous threat, making the corpse a site of latent potential; its blood may no longer flow, but a fresh supply is never far away.

References

- Byron, George Gordon. “Augustus Darvell.” In The Vamypre and Other Tales of the Macabre. Edited by Robert Morrison and Chris Baldick. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2008, 246-251.

- Bailie, Helen T. “Blood Ties: The Vampire Lover in the Popular Romance.” The Journal of American Culture 34, no. 2 (2011): 141-148.

- Freud, Sigmund. “The Uncanny.” In The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, Volume XVII (1917-1919): An Infantile Neurosis and Other Works. Translated by James Strachey. London: The Hogarth Press, 1955, 217-256.

- Lever, Charles. “Post-Mortem Recollections of a Medical Lecturer.” In The Vamypre and Other Tales of the Macabre, 165-174.

- Polidori, John William. The Vampyre. In The Vamypre and Other Tales of the Macabre, 1-24.

- “The Victim.” In The Vamypre and Other Tales of the Macabre, pp. 87-98.

- Willis, N. P. “My Hobby,—Rather.” In The Vamypre and Other Tales of the Macabre, 139-142.

- The Vampyre: A Tale. By Lord Byron [or Rather, by J. W. Polidori]. Illustrated by F. Gilbert. (People’s Edition.) [With a Portrait.]. 1884. Held by the British Library. https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/illustrated-edition-of-the-vampyre.

End notes

- Sigmund Freud, “The Uncanny,” in The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, Volume XVII (1917-1919): An Infantile Neurosis and Other Works, trans. James Strachey (London: The Hogarth Press, 1955), 221.

- George Gordon Byron, “Augustus Darvell,” in The Vamypre and Other Tales of the Macabre, ed. Robert Morrison and Chris Baldick (Oxford: Oxford UP, 2008), 251.

- Ibid.

- John William Polidori, The Vampyre, in The Vamypre and Other Tales of the Macabre, 18.

- Ibid, 3.

- Ibid.

- Ibid, 7.

- Ibid, 23.

- Helen T. Bailie, “Blood Ties: The Vampire Lover in the Popular Romance,” The Journal of American Culture 34, no. 2 (2011): 145.

- “The Victim,” in The Vamypre and Other Tales of the Macabre, 92.

- N. P. Willis, “My Hobby,—Rather,” in The Vampyre and Other Tales of the Macabre, 140.

- Ibid, 142.

- Freud, “The Uncanny,” 226.

- Charles Lever, “Post-Mortem Recollections of a Medical Lecturer,” in The Vamypre and Other Tales of the Macabre, 172.

- Ibid.

- Ibid, 174.

EMILY CLINE is a second-year Master’s student in the Department of English at McGill University. Her primary research interests are nineteenth-century British literature and culture, women’s and gender studies, and the history of science and medicine. She currently works as a research assistant in McGill’s Department of the Social Studies of Medicine.

Submitted for the 2019–2020 Blood Writing Contest

Leave a Reply