Danielle Dalechek

Norfolk, Virginia, United States

“Who has fully realized that history is not contained in thick books but lives in our very blood?”

— Carl Jung

Historically, the opposite of purity was often viewed and represented as evil. This was especially true if you happened to be a woman. Even the most chaste and abiding women in society could still be considered impure and able to contaminate or even poison others. While this stigma was not apparent in childhood, it would be attached upon menarche.

Menstruation fears and taboos have existed in many early cultures despite a diversity of social and religious composition. In Buddhist practices in Sri Lanka, for example, menstrual bleeding was considered a threat to both cosmic purity and society overall. La Fontaine in 1672 explained that “a menstruating (Gisu) woman must keep herself from contact with many activities lest she spoil them: she may not brew beer nor pass by the homestead of a potter lest his pots crack during firing; she may not cook for her husband nor sleep with him lest she endanger both his virility and his general health. . . . during the time that she is menstruating she must not touch food with her hands: she eats with two sticks.”1

Menstrual blood, artwork title “Floral 1”. Credit: Beauty in Blood. CC BY 4.0.

While these measures probably sound extreme, even today playful words are used to describe menstruation in order to avoid accurate depictions and ensure a separation from the visceral imagery of blood, such as “shark week, that time of the month, a visit from Aunt Flo, on the rag, the crimson tide, or lady business.” Women may no longer be banished to secluded huts during their period, but there is still a dissonance when it comes to society’s comfort level with menstruation.

Scholars, too, held such beliefs. The anthropologist Ashley Montagu suggested “menstruating women indeed wither plants, turn wine, spoil pickles, cause bread to fall, and so forth because of chemical components in their menstrual blood.”1 This theory of chemicals or toxins is credited to Bela Schick, a physician who described menstrual blood as containing “bacterial menotoxins.”1 These concepts cannot be meaningfully discussed without also addressing the concept of hysteria, which has been mentioned as early as 4000 years ago in ancient Egypt.

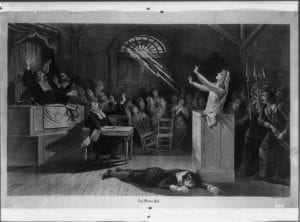

In the Middle Ages, syndromes considered to be of a hysterical nature came to be conceived as “products of witchcraft, demon possession, and sorcery that also had historical associations with dissociative phenomena.”2 The term hysteria was derived from the Greek word hystera, meaning the uterus. The underlying theory was that the uterus became displaced from its normal pelvic placement and wandered through the body. This “wandering womb” created symptoms in the various places that it passed, thus causing “hysteria.”

Some depictions of hysteria included the idea that the uterus was capable of such problems because it was full of blood. Cures varied, but included extreme measures such as bloodletting, hysterectomy, clitoridectomy, or placement in asylums. Bloodletting was not a surprising choice of treatment because of the belief of having too much blood or bad fluids, and the idea of a dark or evil supernatural influence that needed to be released via the bloodstream.

Still, it was not all maliciousness and fear. The Imperial Romans believed menstrual blood held positive magical properties, such as encouraging the fecundity of wheat fields and providing therapeutic applications for gout, goiter, puerperal fever, worms, and even headache. In Morocco, menstrual blood was used in dressings to treat open sores and wounds. Some of these practices held a preference for “virgin blood” in particular, confirming a symbolic quality rather than practical reasoning.

The inherent “power” of menstrual blood was at the mercy of religion; with beliefs ranging from evil and polluting to holy and healing. In societies where the outside world was viewed as dangerous, the more dangerous menstrual blood was deemed to be. These ideas projected onto women’s bodies allowed men to simultaneously control and remain dissociated from the reproductive cycles and functions of women.

References

- Buckley, T., Gottlieb, A. Blood Magic: The Anthropology of Menstruation. University of California Press, 1988. 5-30.

- North CS. The Classification of Hysteria and Related Disorders: Historical and Phenomenological Considerations. Behav Sci (Basel). 2015;5(4):496–517. Published 2015 Nov 6. doi:10.3390/bs5040496

- Bani M, Giussani B. Gender differences in giving blood: a review of the literature. Blood Transfus. 2010;8(4):278–287. doi:10.2450/2010.0156-09

DANIELLE DALECHEK lives on the Bay in Norfolk, VA, and just completed a Master’s in Healthcare Analytics from Eastern Virginia Medical School. Currently working as a scientific communications writer, she has also worked in neuroscience and cardiology research. She enjoys cooking a variety of spicy foods, hiking, kayaking, reading (especially sci-fi and horror), and making art for local shops and charity. By Fall of 2020, she plans to begin working towards a PhD in Neuroscience or Biostatistics.

Submitted for the 2019–2020 Blood Writing Contest

Leave a Reply